Much of our work at KITAB involves comparing books in order to understand their relationships. Our main tool for this is the passim software, which detects passages two texts have in common (here are some of our blogs about passim: 1, 2, 3, 4). passim produces a lot of data about each pair of passages, including where exactly in both books these passages are found, and how many words and characters the shared passage contains in either book.

For each pair of books, this data is collected in a csv file, which can be loaded into a spreadsheet. In this form, the data is not very human-reader-friendly. In order for us to get an understanding of what all these rows and rows of data mean for the relationship between two books, we use visualizations.

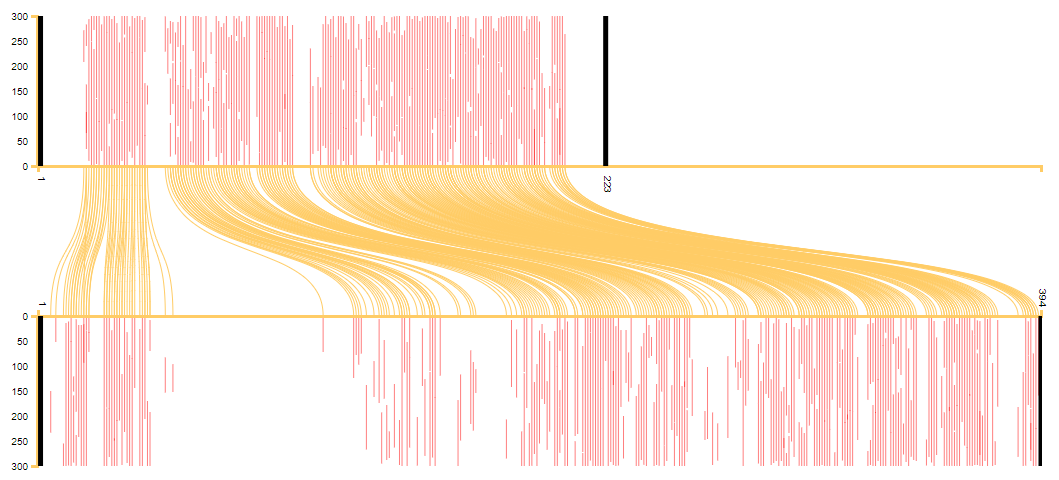

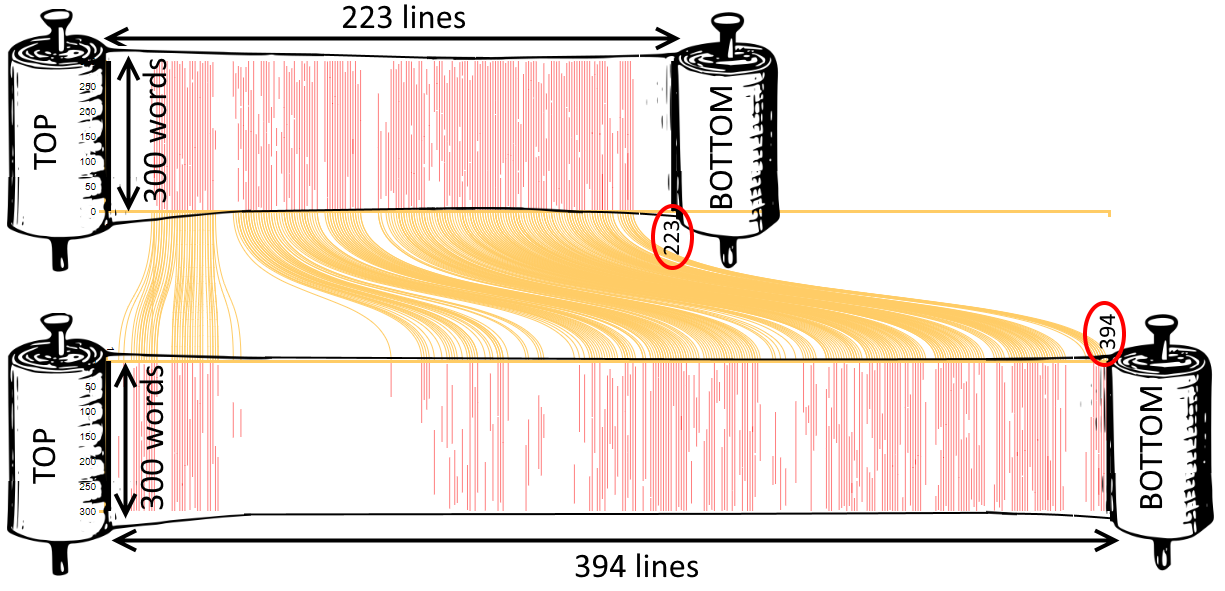

The most common visualization we use to visualize the overall relation between two books, and which is familiar to anyone who has ever read a blog post or attended a lecture on the KITAB project, is what we have started to call our 'scroll' visualization (see Figure 1) - that is scroll in the old-fashioned sense of a rolled-up strip of paper, not the digital-age thing you do with a mouse or on your phone. The team has also been referring to this visualization as the “pairwise visualization”, because it is the visualization we most commonly use to compare pairs of books.

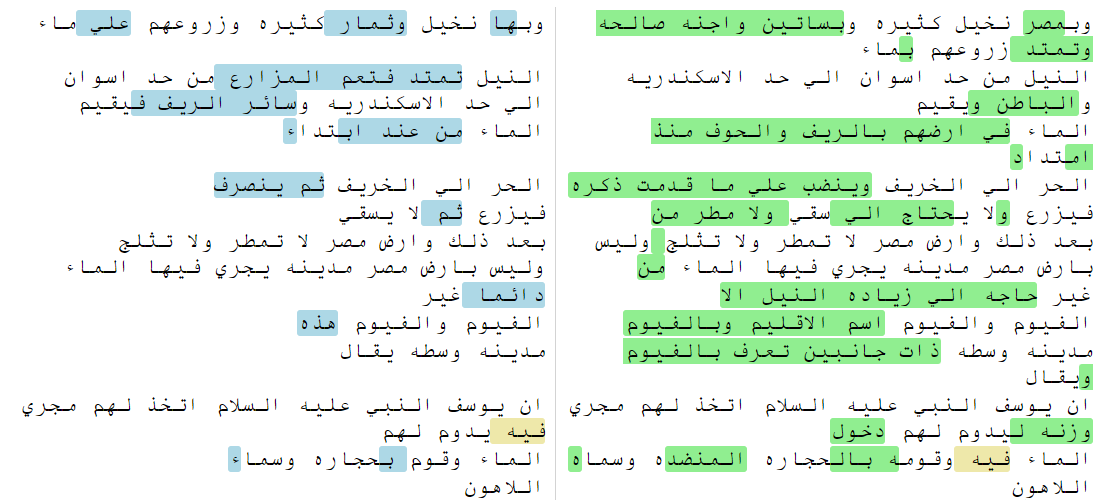

Figure 1: scroll visualization of the text reuse between al-Istakhri’s Kitab al-Masalik wa-al-mamalik (top) and Ibn Hawqal’s Kitab Surat al-ard (bottom).

This is how you read this visualization (see Figure 2): imagine that we write out the text of both books we compared on a very large scroll, 300 words per line. We then highlight passages that are in both scrolls in red, and connect the location of the passage in scroll 1 to that in scroll 2 with a yellow line (we considered briefly calling this visualization our 'spaghetti' visualization after these yellow lines). Finally, we zoom out so far that we can only see the highlighted passages and the connecting lines.

Figure 2: How to interpret a scroll visualization.

The red lines give us an impression of how much of the book is reused in the other book, while the yellow lines help us see whether the common passages occur in the same order in both books. In the example in Figures 1 and 2, the red lines show that much of al-Istakhri’s work is reused in Ibn Hawqal’s, and the absence of red lines in some sections of the book shows that Ibn Hawqal did not reuse some sections but added his own information there. (People who know the books will immediately suspect that the large blank section in the first quarter of Ibn Hawqal’s book must be his description of the Maghrib, which is entirely independent from al-Istakhri’s). Meanwhile, the fact that the yellow lines all run nicely parallel shows us that Ibn Hawqal faithfully followed the structure of al-Istakhri’s book. For examples where this is not the case, see Sarah Savant’s blog on the different versions of Malik’s al-Muwatta.

KITAB DiffViewer

The scroll visualization is very useful for comparing books at a high level. For fine-grained comparisons of the differences and similarities between passages identified by passim as text reuse, we until recently used an online tool called Diffchecker.

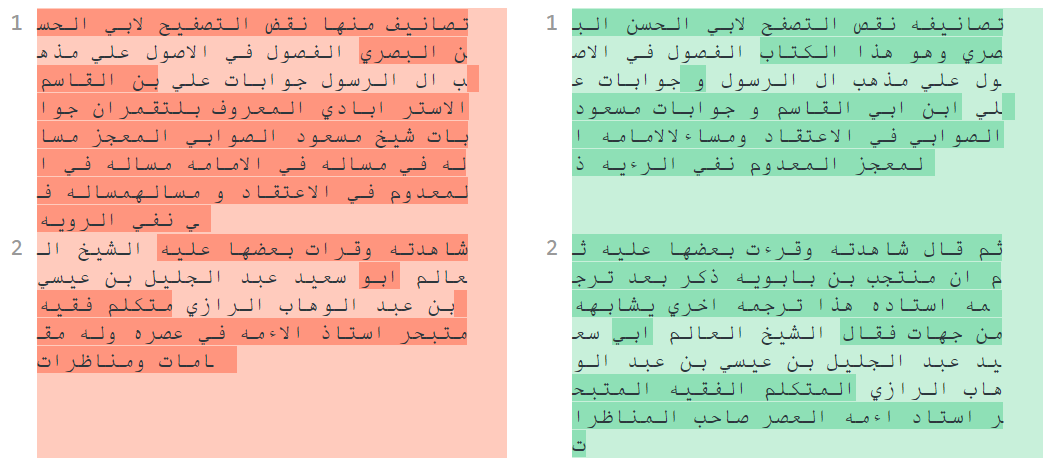

Figure 3: Diffchecker visualization of a passage from Muntajab al-Din’s Fihrist (left) and Agha Buzurg Tihrani’s Dhariʿa (right). Differences are highlighted in darker shade.

The tool highlights words that are different between two passages in a darker shade, but it does not do a very good job with Arabic texts: it does not display right-to-left text correctly, and it cannot deal well with the small differences between tokens caused by prefixes and suffixes. From looking only at the coloured areas, not the text, in the example in Figure 3, we get the impression that there are only two short sections in the passage that are similar in both texts. However, when we look closer at the text, we can see that already the first word is highlighted as different, although it is exactly the same, albeit that the Dhariʿa (the text on the right) adds the suffix -hu at the end of the word (تصانيف vs تصانيفه). Similarly, the third word in the Fihrist is identical to the second word in the Dhariʿa, except for a dot on the last letter (نقص vs نقض).

It’s hard to blame the tool for this: like many similar tools, it was mostly designed to detect changes in computer code. Such a comparison between two versions of the same code is called a 'diff' in computer speak - hence the tool’s name 'diffchecker'.

I looked into many other online diff tools, hoping to find one that would work better for our texts. Unfortunately, all tools I checked had the same problem. The most promising one seemed to be wikEd-diff, a program written to detect and highlight edits in wikipedia articles (see Figure 4). Designed to work with prose written in human languages rather than computer code in mind, it does a better job at catching differences and similarities between two passages of Arabic text, even at a sub-word level. Moreover, it is the only tool I found that can detect blocks of text that were moved rather than added or deleted. Contrary to Diffchecker and other similar tools, however, it displays the two fragments in a single composite (Frankenstein-like) text, with different colours for text that is present only in fragment 1 or fragment 2 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: wikEd-diff visualization of the same two passages as Figure 3, generated with the wikEd-diff online demo tool. Text that is only in fragment 1 (from Muntajab al-Din’s Fihrist ) is highlighted in blue, text that is only in fragment 2 (from Agha Buzurg Tihrani’s Dhariʿa ) in orange. Text that is present in both fragments but in a different location is placed where it appears in fragment 2 and highlighted in grey; at its location in fragment 1, an arrow is inserted, and when you hover over the arrow with the mouse, the corresponding text in the other fragment is highlighted in a darker grey.

This is not easy to read: the display looks cluttered and although the tool selected more text as common to both fragments than Diffchecker, the fact that both alternatives are displayed in the same composite text gives the impression there is much more difference than similarity between the two text fragments.

After giving up hope for an out-of-the-box solution, I started searching for javascript or Python libraries that can be used for analysing and displaying the difference between two strings of text, and which I could use to build a diff tool for our OpenITI texts myself. Again, there are plenty of those (I tried diffchecker, prettydiff, mergely, diff2html, jsdiff, diff-match-patch, text-diff) but almost all of them are focussed on displaying diffs between two versions of the same program code, rather than prose texts in human languages.

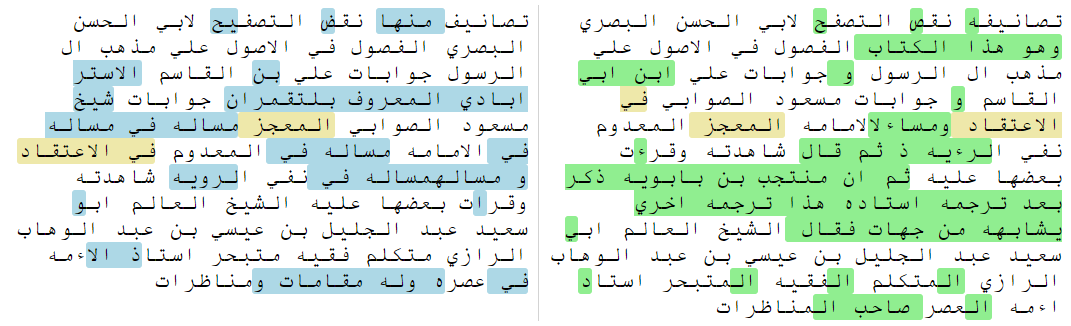

In the end, the best option seemed to be to use the wikEd-diff javascript code to analyse the differences and similarities between the two passages and then to parse and manipulate its html output in order to display both passages in separate fields rather than as one composite text (Figure 5).

Figure 5: wikEd-diff output, refined and split into two separate texts (colour coding: blue: only in fragment 1; green: only in fragment 2; orange: in both fragments but in different positions).

I also wrote a script to refine the output of the wikEd-diff code to make it handle differences below the word/token level in a better way. Compare, for example, how wikEd-diff marks the first word in the example strings, تصايف / تصانيفه (tasanif / tasanif-hu), as entirely different (Figure 4), and how the refined output (Figure 5) marks only the suffix -hu as different. In the appendix, I will go into a bit more technical detail on how this was done.

The end result is that the commonalities between the two texts are much clearer with the OpenITI Diff Viewer than with diffchecker or the raw wikEd-diff output.

I have embedded this code in an online app that is publicly available at https://kitab-project.org/diffViewer/ .

Figure 6: OpenITI Diff Viewer interface after loading two texts.

The app was optimized for use with our OpenITI texts: for example, by default, all OpenITI mARkdown tags (and all punctuation) are stripped away, and all alif-hamza combinations, ta’ marbutas/final ha’s and alif maqsuras/final ya's are normalized. These settings are optional, however, and can be (de)selected in the Options field (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Diff Viewer options

The app has more options: the most useful,in my opinion, is that you can divide the output into lines to make it easier to read the passages side by side (Figure 8). It is usually easy enough to read the beginning of an alignment, but after a couple of lines, it becomes hard to follow where you are in the other fragment, especially if there are many additions/deletions on both sides. This option makes sure that after a divergence between both fragments, both start on the same new line from the point onwards where they converge again.

Figure 8: splitting the output into lines for easier reading (compare to Figure 6!).

Finally, you can download the diff as an image file by clicking the ‘Download png’ or ‘Download svg’ buttons. Before downloading the image, you can resize the text fields by dragging the right-most margin of the image, and change the font size in ‘Options’, so that it fits the layout of the publication you want to use it in.

In the future, we would also like to provide an option by which you can create a permalink to your diff output, which you can then link to in a publication. This has not yet been implemented, however.

Reuse heat map

On the other end of the spectrum, we would sometimes like to be able to visualize all reuse one text has in common with all other texts in the corpus (or a selection).

One way I came up with to do this is to use a heat map: a visualization that indicates by the use of colours how intensely each part of a text has been reused.

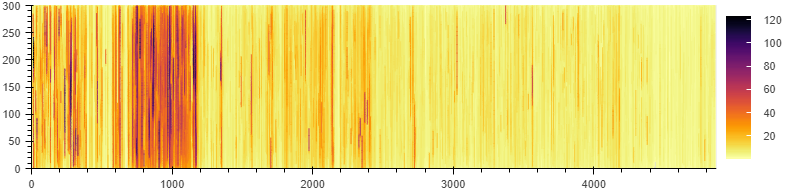

Figure 9: heat map of the reuse of al-Tabari’s Tarikh . The number of times each character in the text features in a reuse alignment detected by passim is indicated by colours (see the colour scale on the right).

Take, for example, the heat map of text reuse of al-Tabari’s Tarikh (Figure 9). The visualization works in a similar way to the book-to-book scroll visualization (Figure 2): the graph represents a scroll, in which each line represents 300 words. Whereas the book-to-book visualization highlights all passages both books have in common in red, this visualization highlights each character in a colour that reflects the number of times it appears in an alignment with another text in the corpus, as detected by passim: in the example in Figure 9, any sections marked in light yellow feature less than 10 times in a reuse instance, while those marked in dark purple were reused up to 120 times.

This allows us to see that not all parts of the texts were as intensively reused as others: there is a clear concentration of darker (more reused) passages between (roughly) lines 700 and 1200. We can go back to the text to find out which section is so much more intensively reused than the other sections of the work: each 300-word section that is represented by a line in the scroll is marked in OpenITI texts with a numbered 'milestone' tag within the text (for example, the end of the first 300-word chunk in the text is marked with the tag `ms001`). Using these milestone numbers, we can see the intensively reused section in the heatmap agrees with the section on the life of the Prophet Muḥammad: the section titled al-qawl fi al-sira al-nabawiyya starts in the milestone 685, while the section on Muḥammad’s death ends in al-Ṭabarī’s text in milestone 1176.

Heat maps can also be used to investigate the spread of reuse over time. One useful application is to split the text reuse into reuse of earlier and later works.

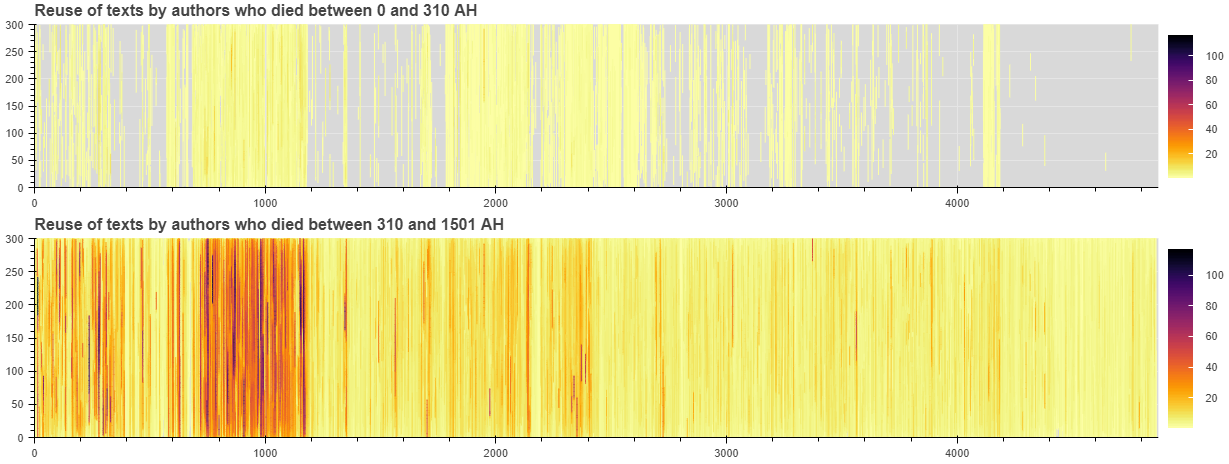

Figure 10: text reuse of al-Tabari’s Tarikh in books written by authors who died before and after al-Tabari.

Figure 10 clearly shows that the material al-Tabari used for his Tarikh is only partially known from older sources in the corpus: especially the sections between the death of the Prophet and the start of the Umayyad period, and the later ʿAbbāsid period are sparsely documented. Of course, this does not mean that al-Ṭabarī uses original material here; rather, that the material he used did not make it into the corpus. Especially interesting in this sense is the tight-knit block of reuse just between lines 4100 and 4200: when we look at where this reuse comes from, we can see that it comes from the only extant part of Ibn Abi Tahir Tayfur’s Kitab Baghdad. It is therefore very likely that if the rest of that book were extant, passim would detect much more reuse for the Abbasid part of the Tarikh. Sarah Savant1 has argued for al-Tabari’s heavy reuse of Ibn Abi Tahir’s text (without mentioning the author) based on an analysis of al-Tabari’s citation patterns in the Tarikh.

We can also split up the reuse data of the later sources into smaller periods, to see whether the reuse is more or less evenly spread over time. For example, if we split up the reuse of Tabari’s Tarikh in later texts into 200-year periods (Figure 11), we see that the section on the life of Muhammad consistently remains the heaviest reused section, but that the later parts of the work lose their importance after the 10th hijri century.

Figure 11: Reuse of al-Tabari’s Tarikh in later texts, grouped by 200-year periods

This visualization is generated using a Python script; the heatmaps it outputs are interactive (you can zoom in, and get a count of the number of times a specific word is reused when you move your mouse over a coloured bar; it could also show the URIs of all texts that reuse those specific words). See an example here.

In the coming months, we will build a publicly available online app to build such heatmaps, to be released when the KITAB data becomes available.

Bibliography

Heckel, Paul, ‘A Technique for Isolating Differences Between Files’, Communications of the ACM 21/4 (1978), 264-268.

Savant, Sarah Bowen, ‘Al-Ṭabarī’s Unacknowledged Debt to Ibn Abī Ṭāhir Ṭayfūr’, forthcoming.

Appendix

The wikEd-diff code is an implementation of an algorithm consisting of six steps, first described by Paul Heckel in his 1978 article ‘A Technique for Isolating Differences Between Files’. The algorithm tries to find the most likely steps by which one string (s1) was turned into another string (s2) by three different types of actions: insertion, deletion, moving. The idea is simple: both strings (s1 and s2) are split into tokens, and tokens that appear exactly once in each string are used as anchors. Next, the tokens before and after those anchors are compared in a number of further steps. The end result is that each token in s2 is marked as either common to both strings, or inserted / deleted / moved to another position in s2 as compared to s1.

The WikEd-diff code outputs a single html string in which the inserted, deleted and moved characters are enclosed in span tags with different classes for each type (see Figure 5):

-

inserts: `class="wikEdDiffInsert"`

-

deletions: `class="wikEdDiffDelete"`

-

moves: characters in s2 are in a span with `class="wikEdDiffBlock"`, while the position of these characters in s1 is marked with a placeholder character in a span with class `wikEdDiffMarkRight` or `wikEdDiffMarkLeft` (depending on whether the text was moved to the left or right in s2)

Characters that both strings have in common are included as plain text (without tags).

Figure 12: Simplified and abbreviated extract of the output of the wikEd-diff code. Spans are highlighted in the same colours as in Figure 4.

I wrote a script that splits this composite html text into two separate html strings (output1 and output2) in order to display them side by side: untagged (shared) text is added to both output strings, `wikEdDiffInsert` and `wikEdDiffBlock` spans only to output2, `wikEdDiffDelete` and `wikEdDiffMarkRight`/`wikEdDiffMarkLeft` spans only to output1 (Figure 13).

Figure 13: wikEd-diff output split into two separate texts (blue: only in s1, green: only in s2, orange: in s1 and s2 but in different positions). Generated from the wikEd-diff output in Figure 4.

This works, but I noticed that the output of the wikEd-diff code is not as fine-grained as we’d like: more often than not, it will tag an entire word as insertion/deletion even if the only difference is a prefix or a suffix, or a single character. For example, in the first line of Figures 4, 12 and 13, you can see that like diffchecker, wikEd-diff marks تصايف / تصانيفه (tasanif / tasanif-hu) as entirely different tokens, although they differ only by one character. The same goes for the words نقص / نقض and التصفح / التصفيح on the same line.

Figure 14: wikEd-diff output split into two separate texts (blue: only in s1, green: only in s2, orange: in s1 and s2 but in different positions) and refined using shingled 3-grams.

As a next step, I wrote my own implementation of (the first five steps) in Heckel’s algorithm in order to finetune the output of the script: each text inside a span is divided into shingled n-grams (default: n = 3 characters; this can be changed under “Options” in the app, see Figure 5), and then these n-grams are used as tokens for Heckel’s algorithm. This significantly improves the output: for example, in the first line of Figure 14, you can see that the refined output correctly identifies the word تصانيف as shared between both strings, with only the suffix -hu ه tagged as addition in string 2. Similarly, only the last letter in نقص / نقض is tagged as different in both strings.

-

Sarah Bowen Savant, ‘Al-Ṭabarī’s Unacknowledged Debt to Ibn Abī Ṭāhir Ṭayfūr’, forthcoming. ↩