Text reuse is the term that we use to describe cases where one book shares verbatim material with another. Text reuse can be studied manually through the reading of texts in parallel, but it can also be detected computationally, using the passim algorithm. Computational approaches, which can compare thousands of books at once, can teach us many exciting things about Arabic book history that would be impossible to discover through manual study.1 In this blog post, I would like to make some observations about passim’s outputs at the level of individual alignments (the paired passages produced by passim) rather than larger book relationships and through them discuss how the human evaluation of passim’s outputs can improve the algorithm’s performance. A key point I would like to make here is that passim is powerful, but it cannot understand the content of texts, sometimes leading it to identify cases of similarity between texts that do not constitute meaningful reuse.

Identifying meaningful reuse

In order to detect reuse, the passim algorithm makes a series of assumptions about what constitutes meaningful reuse. Two key criteria are the following:

-

the minimum number of words that need to be shared between two passages for a match to be considered a reuse case (the min-match parameter)

-

the maximum length of a gap between the shared words in two passages before it is either broken into two reuse cases or not considered a reuse case (the gap parameter)

If passim’s assumptions about the nature of meaningful reuse are incorrect, it will either output meaningless alignments or miss cases of meaningful reuse. This is particularly an issue when passages contain similar names. Table 1 gives an example of the kinds of alignments that are produced if the gap parameter is too long.

| Ibn Saʿd, Kitab Tabaqat al-Kubra (viii: 91) | Al-Tabari, Taʾrikh al-Rusul wa-l-Muluk (iii: 167) |

|---|---|

| زينب بنت خزيمة بن الحارث بن عبد الله بن عمرو بن عبد مناف بن هلال بن عامر بن صعصعة وهي أم المساكين كانت تسمى بذلك في الجاهلية أخبرنا محمد بن عمر حدثنا محمد بن عبد الله عن الزهري قال كانت زينب بنت خزيمة الهلالية تدعى أم المساكين وكانت عند الطفيل بن الحارث بن المطلب | وممن لم يذكر هشام في خبره هذا ممن روى عن رسول الله ص أنه تزوجه من النساء زينب بنت خزيمة وهي التي يقال لها أم المساكين من بني عامر بن صعصعة وهي زينب بنت خزيمة بن الحارث ابن عبد الله بن عمرو بن عبد مناف بن هلال بن عامر بن صعصعة وكانت قبل رسول الله عند الطفيل بن الحارث بن المطلب |

Table 1: A passim alignment matching a biographical entry for Zaynab bt. Khuzayma (a wife of the Prophet) from Ibn Saʿd’s Tabaqat with al-Tabari’s account of the Prophet’s marriage to Zaynab. You can see from the underlined words that passim has matched Zaynab’s full name, in addition to the phrase ʿinda al-tifayli bin al-harithi bin al-muttalibi. In addition, passim may have identified that both passages use Zaynab’s epithet umm al-masakin (highlighted). Because a large gap has been allowed in the first passage between Zaynab’s full name and the final shared lines, the two matched passages are not meaningfully related.

For any clear understanding of the nature of text reuse in our corpus, we must ensure that passim locates the maximum possible instances of text reuse, without falsely identifying instances such as that in the example above. One solution is to computationally locate names of individuals within the texts and then exclude those from passim’s analysis. This is currently being explored by Ryan Muther through the automatic detection of isnads (see further Tracking Traditions: Identifying Isnads in the OpenITI Corpus). Additionally, it is important to establish a set of ground truths against which to evaluate passim’s performance and to experiment with different parameters. This is done through the manual annotation of text reuse and/or correction of passim alignments.

The process of creating evaluation data

My research is concerned with identifying cases of text reuse in order to understand the survival of ‘lost’ Fatimid texts into the ninth/fifteenth century. For this research, I read through and closely compared texts that describe a ten-year period of Fatimid history. This led me to identify an instance of significant reuse between two texts by the famous Mamluk historian al-Maqrizi (d. 845/1442): the Ittiʿaz al-hunafaʾ (a chronicle of the Fatimids) and the Kitab al-Muqaffa al-kabir (a biographical dictionary). An exhaustive comparison of sections of these two works identified instances of text reuse, which could be used to evaluate passim’s performance.

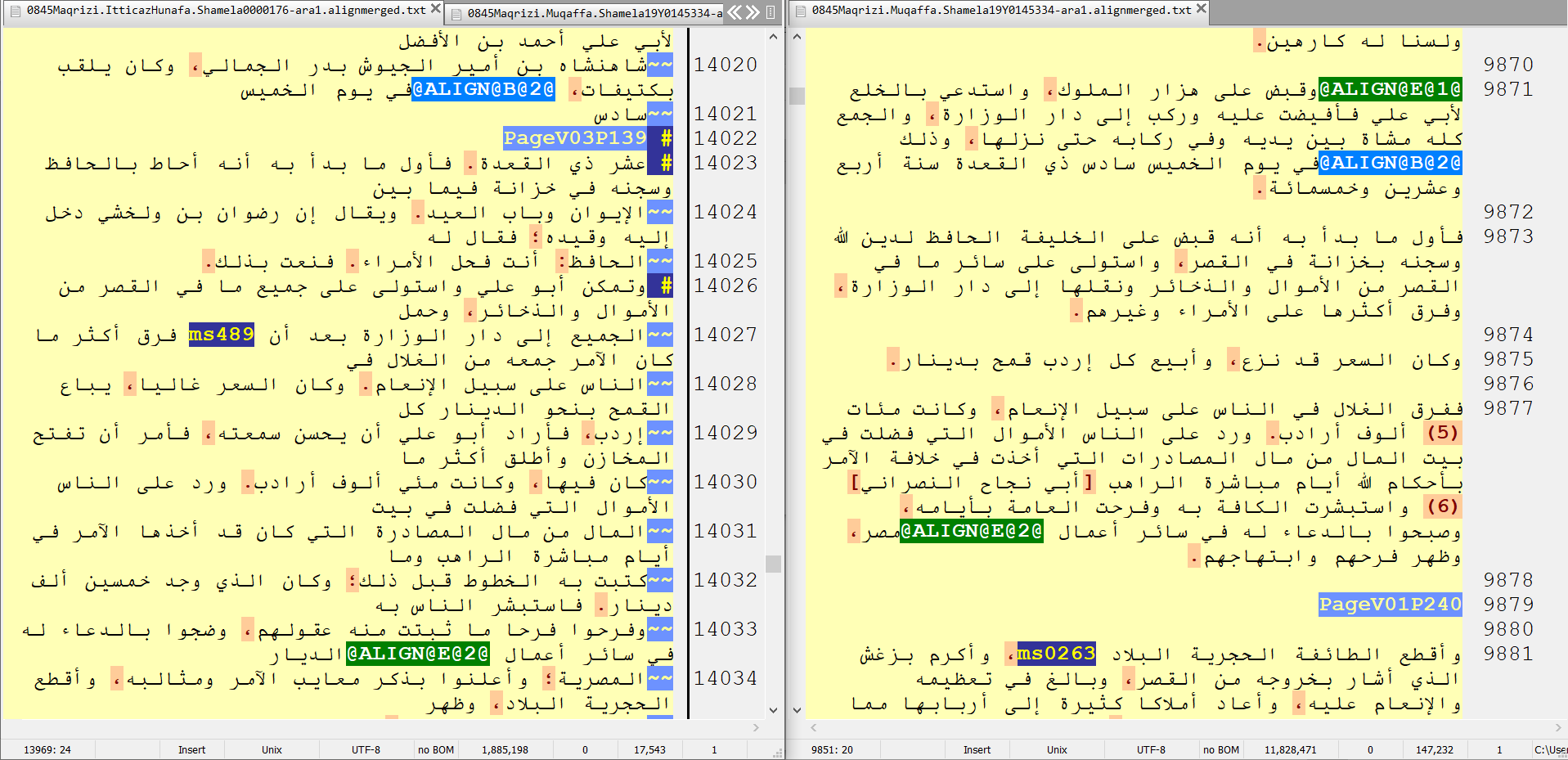

Passim was run on the chosen pair of books, and tags were inserted identifying where passim had located passages of reuse.2 These tags are in pairs, constituting a beginning and an end tag with a shared unique identifier (UI) number (e.g. @ALIGN@B@2@ and @ALIGN@E@2@). The UI number is specific to the passage as it is tagged in both books. Figure 1 gives an example of the tags in parallel texts:

Figure 1: A side-by-side view of corresponding automatic alignment tags in al-Maqrizi’s Ittiʿaz (left) and his Muqaffa (right). (The text files are open in EditPad Pro with a training-data annotation schema applied to facilitate the easy identification of tags.)

The corresponding alignments were then checked, with tags inserted or removed where needed. A distinct pair of tags (@ALB@1@ and @ALE@1@) was used to easily differentiate a manually created tag from one generated by passim.

When doing this type of evaluation, I am asking three questions:

-

Has passim entirely missed any cases of text reuse?

-

Has passim identified unrelated text as reuse?

-

Are the edges of the reuse correct – does the reuse start or end before or after the tags?

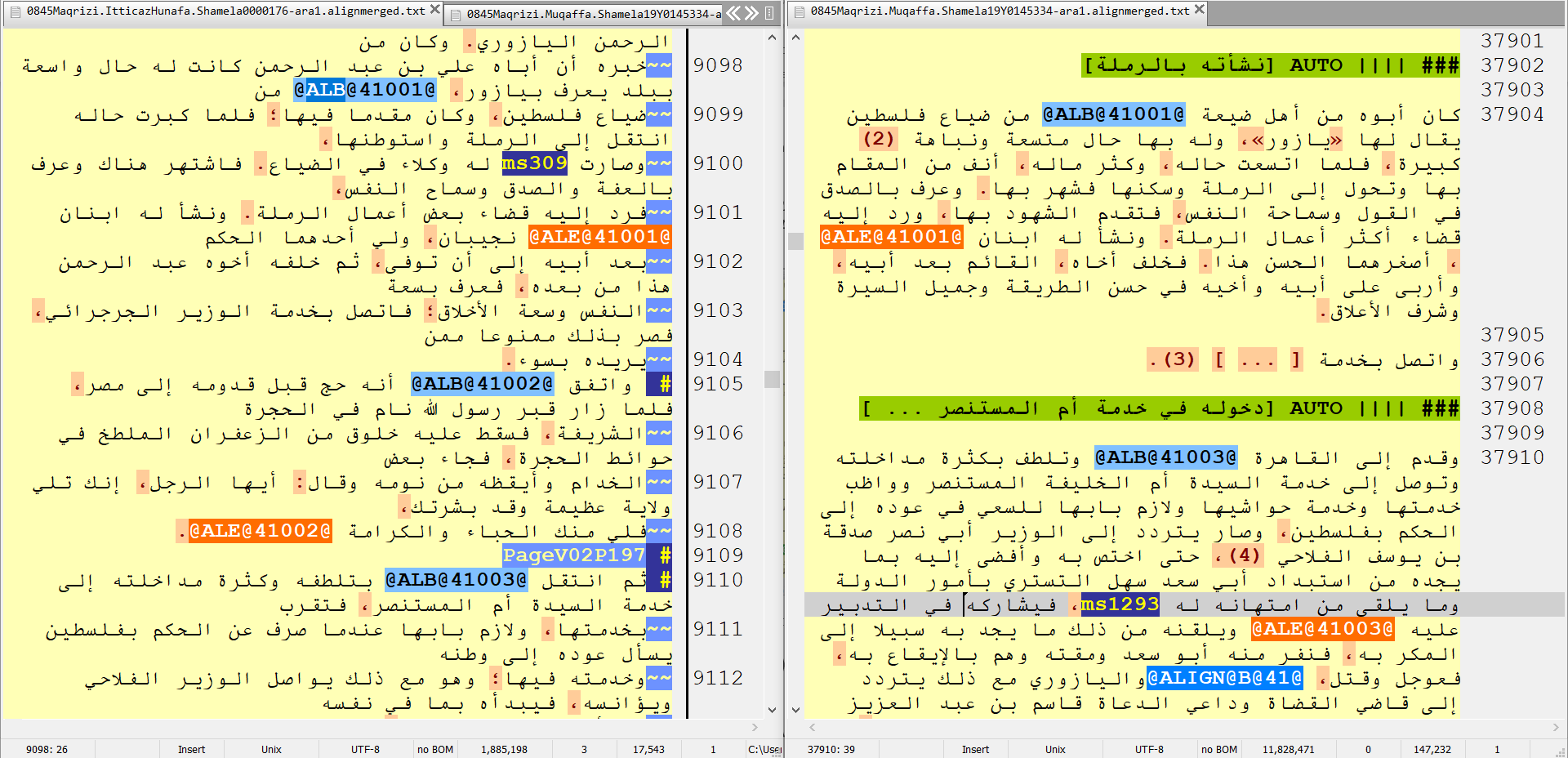

Figure 2 gives an example of parallel texts with manually evaluated alignments:

Figure 2: A side-by-side view of corresponding alignment tags with manual correction in al-Maqrizi’s Ittiʿaz (left) and his Muqaffa (right).

Some observations: Human vs. machine

The process of evaluation described above might sound particularly tedious and dull, but it is a valuable exercise for understanding both our texts and our methods. On the one hand, reading text reuse alignments so closely can teach us a lot about how authors copied, abridged and paraphrased their source texts. On the other, it teaches us about the different strengths of humans and machines in identifying text reuse.

The identification of text reuse is a task at which humans are actually quite poor. As I found in my own research, manual studies in text reuse are limited by two factors:

-

Memory: successfully identifying a case of reuse requires you to remember similarities in language and events.

-

Corpus size: comparing closely by hand can only be done on a relatively narrow corpus, and the assembly of such a corpus will (like it or not) be subject to biases.

Passim does not suffer from these limitations: it can compare across an enormous corpus in a very short period of time (so there is no need to create a selective corpus or focus on a particular subject); it is not hindered by the limits of human memory; and crucially, passim does not get tired or go cross-eyed after hours of closely scrutinising text. In other words, passim allows us to see text reuse at scale without being subject to the biases of text selection or the lack of precision caused by fatigue.

When passim’s outputs were compared with those of my research, the results were very compelling: passim did not falsely identify passages of reuse, and it found nearly all of the instances of reuse I had found through close reading of the texts. In addition, it did not find any meaningful instances of reuse that my own research had not identified. However, passim failed in instances where there was only a limited number of shared words between the texts and where shared words had been reordered – for example, where one work had omitted a long span of text or where lots of synonyms were used in the copy. Table 2 below shows an example of such a case:

| Al-Maqrizi’s Ittiʿaz (ii: 197) | Al-Maqrizi’s Muqaffa (iii: 366-7) |

|---|---|

| وكان من خبره أن أباه على بن عبد الرحمن كانت له حال واسعة ببلد يعرف بيازور، من ضياع فلسطين، وكان مقدّماً فيها؛ فلما كبرت حاله انتقل إلى الرملة واستوطَنها، وصارت له وكلاء في الضياع. فاشْتُهِر هناك وعرف بالعِفّة والصدق وسماح النفس، فرُدّ إليه قضاء بعض أعمال الرملة. ونشأ له ابنان نجيبان، ولي أحدُهما الحكم بعد أبيه إلى أن توفي, ثم خلفه أَخوه عبد الرحمن هذا من بعده، فعُرِف بسعة النفس وسعة الأخلاق، | كان أبوه من أهل ضيعة من ضياع فلسطين يقال لها “يازور“، وله بها حال متّسعة ونباهة كبيرة. فلما اتّسعَت حاله، وكثر مالُه، أنِف من المقام بها وتحوّل إلى الرملة وسكنها فشُهر بها. وعُرف بالصدق في القول وسماحة النفس، فتقدّم الشهود بها، ورُدّ إليه قضاءُ أكثر أعمال الرملة. ونشأ له ابنان، أصغرُهُما الحسن هذا. فخلف أخاه، القائمَ بعد أبيه، وأربى على أبيه وأخيه في حسن الطريقة وجميل السيرة وشرف الأعلاق |

Table 2: A formatted version of alignment 41001 shown in figure 2 above. The underlining shows text reuse. For the human reader, it is clear from the subject matter and the patterns of similarity that al-Maqrizi is copying from the same source text, but because the number of shared words is relatively small and the gaps between shared words large, passim was unable to align these two passages within its current parameters.

These cases show an evident shortfall of passim when compared to manual study. Any researcher comparing the texts understands the content and relies on this to find instances of text reuse. Whereas passim goes through the text and pairs up words and phrases irrespective of their meaning, the researcher often relies on the meaning of the text to find instances of text reuse. In my own research, for example, I created a spreadsheet cross-referencing the events before proceeding to compare the texts. This means that researchers are not thrown off by the use of synonyms or when certain words are omitted but the overall meaning is retained.

To an extent, passim can be taught to recognise these marginal cases of text reuse. By creating a body of evaluation data, the alignment model will learn what kinds of patterns to associate with text reuse, including such marginal cases. This case study illustrates the importance of cooperation between computer scientists and humanists for high-quality research in text reuse and book history. Without computational techniques, it is impossible to understand text reuse at scale, and as a result our studies would remain narrow and at risk of bias. Yet without subject specialists, passim cannot learn what constitutes meaningful reuse.

-

For examples, see Algorithmic Reading of Shiʿi Hadith Collections: Direct Borrowing and Common Sources and On Commentaries, Digressions, Transtextualities and Rabbit Holes. ↩

-

The editions used for the comparison were al-Maqrizi, Ittiʿaz al-hunafaʾ bi-akhbar al-aʾmma al-fatimiyyin al-khulafaʾ, ed. Muhammad Hilmi Muhammad Ahmad, vol. 2 (Cairo, 2008), and al-Maqrizi, Kitab al-Muqaffa al-kabir, ed. Muhạmmad al-Yaʿlawi, vol. 3 (Beirut, 1987). ↩