Tagging the structure of the texts in OpenITI corpus is an important step towards the ultimate goal of the KITAB projectStudying the Arabic textual tradition using text reuse detection (for a detailed description of the tagging process, see my other blog post here). However, its application goes much beyond the aims set for this project. In the first place, it creates a corpus of manually-tagged texts, annotated by human annotators and reviewed by second annotators, to which readers have access, with an interactive space enabling them to suggest corrections for any problem in the tags or in any part of the text itself through the issues reporting mechanism on our GitHub page. Besides, with a touch of creativity, such a corpus developed by spending so much time on preparing each single text can be freely used as a base by specialists who decide to work on specific texts in their area of specialty. In this blog post, I will try to explain how our annotated texts can be used to present enhanced versions of the texts, especially large biographical/bibliographical collections. By enhanced version, I mean a digital (and preferably online) version modified in order to facilitate using the content of the text for readers and also facilitate doing research on the text (or even more broadly on the genre of the text) for specialists. The text I will use here as an example is the famous Shiʿi bibliographical collection al-Dhari’a ila tasanif al-shi’a. Nevertheless, the suggestions and methods presented here are by no means limited to this text and can be applied to any other tagged bibliographical/biographical text on our corpus. To show how our tagged texts can be used for this purpose, first I will briefly explain what I, as the annotator, have done on it and will make some preliminary suggestions to improve the quality of the text; then I will show a few possibilities for the corpus which can be helpful for a wider audience interested in the text.

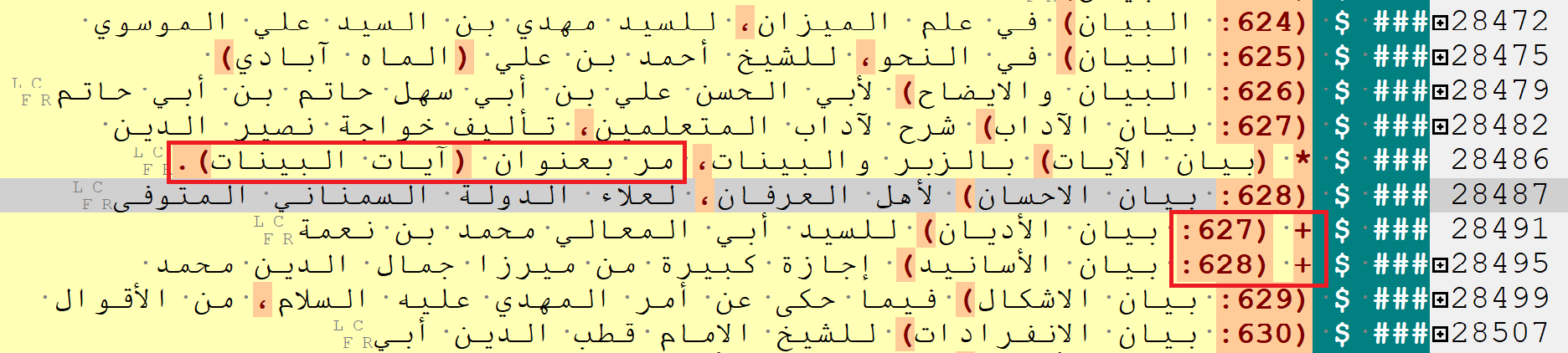

Al-Dhari’a is the largest bibliographical collection indexing the Shiʿi written tradition in Arabic and Persian (and occasionally Turkish and Urdu) in 29 printed volumes and around 55000 entries, compiled by Agha Buzurg al-Tihrani (1293/1876-1389/1970) in a span of 60 years searching through around 60 libraries in several countries from Iran and Iraq to Syria and Egypt (find the PDF here). The text has a very clear structure with numbered entries which are the titles of the texts (manuscripts or published) sorted alphabetically according to the first letter. There are also cross-references which are not numbered. So, as the first step, I tagged all the entries as simple entries (### $), and cross-references with an asterisk (### $ *), and then I checked the sequentiality of the numbered entries through a Python script. Hundreds of numbers were typed incorrectly in our digital version, which I corrected manually. Entries that did not have a number or had duplicate numbers in the printed edition, I tagged with a ### $ + (see Figure 1) (however, it is not known whether such numbering problems should be attributed to the original manuscript or to the typists of the printed edition). In an enhanced digital version, the cross-references would be linked to their main entries, and a secondary numbering system could be set up to correct the incorrect numbers in the printed edition.

Figure 1: Screenshot of the folded text to show only the headers in EditPad Pro: a cross-reference tagged as ### $ * and two duplicate numbers tagged as ### $ +.

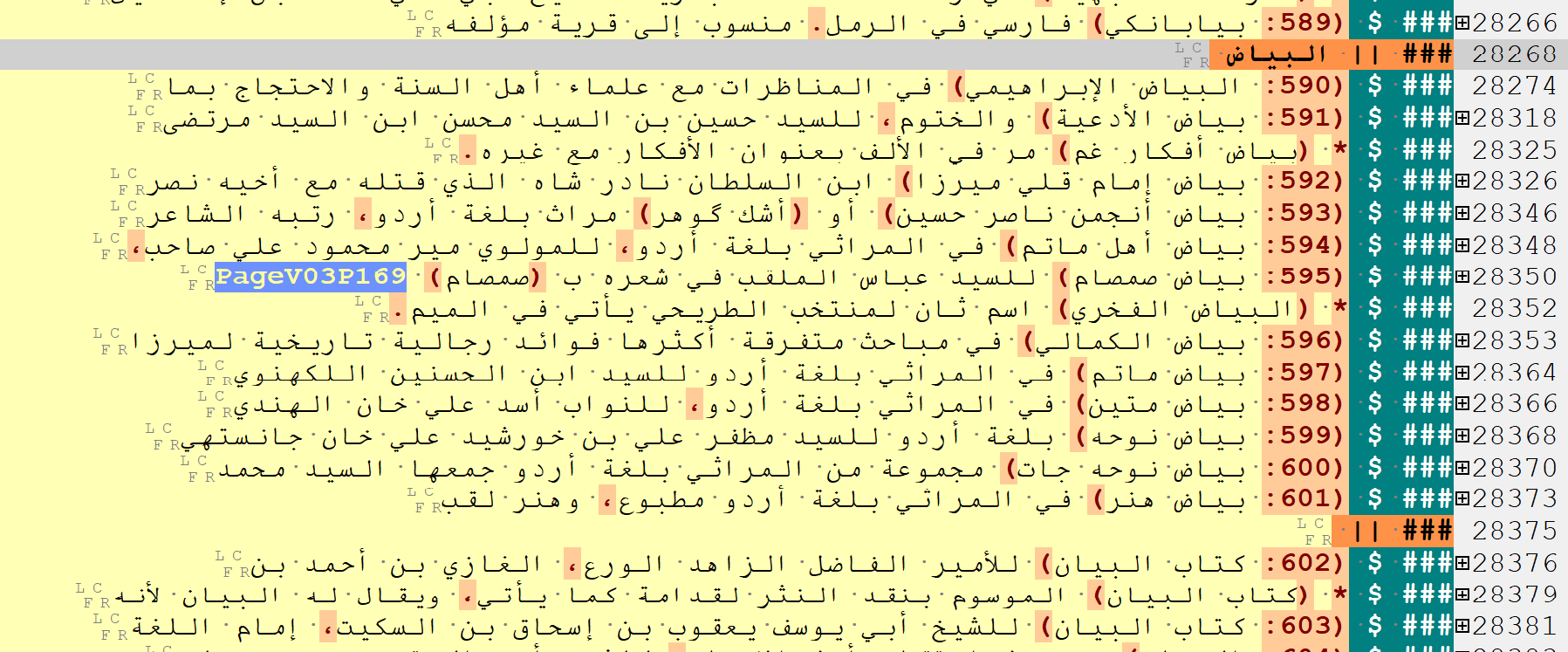

The categorisation of the headers should also be modified in an enhanced version. The entries are sorted according to their first alphabetical letter. So, the first-level headers (tagged with one pipe: ### |) are successive alphabetical letters. Occasionally, the author has introduced second-level headers (tagged with two pipes: ### ||) to group texts that have the first word of the title in common, or belong to a specific genre. Since the OpenITI mARkdown annotation system does not include closing tags, I used blank second-level headers to mark the end of these sections (Figure 2). Appropriate headers can be added in square brackets for all of such sub-categories to facilitate navigation. The other problem in the categorisation of the headers is that in the fourth volume (and in a very few cases in other volumes), after the first-level alphabetical headers, there is an additional layer of headers based on the second alphabetical letter of the entries, which has made the levelling of the whole text inconsistent (see Figure 3). In an improved version, the text could be made more accessible by extending this secondary level based on the second letter to the navigation of the entire text (in a way that makes clear this is done by the annotator, not by the author). So, the first-level headers will be the first alphabetical letter of the entries; the second-level headers will be the second alphabetical letter of the entries; and the third-level headers will be the genre or the first word of the title of the books.

Figure 2: Screenshot of the folded text to show only the headers in EditPad Pro: a blank second-level header (### ||) showing the end of the previous second-level section.

Figure 3: Screenshot of the folded text to show only the headers in EditPad Pro: an additional layer of categorisation applied occasionally in the fourth volume based on the second alphabetical letter of the entries.

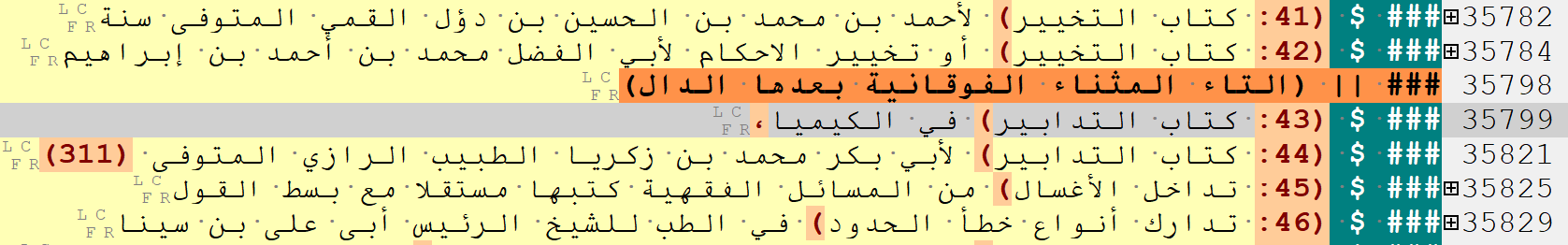

A major issue in most large collections that needs to be dealt with is its appendices or supplements, compiled by the original author or by subsequent writers. In this case, the last volume of the text is an appendix compiled by the original author alphabetically indexing the texts he has found after publishing his book. Besides, the text has several supplements compiled by subsequent authors to complement the entries. An enhanced digital version offers the possibility to add links to these supplements. The entries indexed in the author’s appendix and the ones indexed in the supplements could be integrated into the text using abbreviations showing from which text each entry is drawn. I have created a sample in Figure 4 in which ABT-SUP stands for the entries taken from the author’s supplement; MAR stands for the entries taken from a contemporary supplement written by Muhammad Ali al-Rawadati entitled Takmilat al-Dhari’a ila tasanif al-Shi’a; and MTB stands for the entries taken from another contemporary supplement written by Muhammad al-Tabataba’i al-Bihbahani entitled al-Shari’a ila istidrak al-Dhari’a. Apart from the entries of the supplements, some of the entries indexed in the original text could also be linked to their correct places. The author introduces new texts that should have been mentioned in previous volumes after the phrase ‘قد فاتنا ذكره في محله’. For all such cases, links could be added to the relevant places in previous volumes. I showed one case in the figure with ABT-M which stands for Agha Buzurg al-Tihrani matn. Such an abbreviation system will make a digital version in which the readers have access to all the entries both in the original text and in the supplements in a successive order, while at the same time, the entries belong to each specific text is clearly recognisable, with the ability of adding the entries in newly-found or newly-compiled supplements.

Figure 4: A sample integrating three entries from the supplements plus one from the original text placed in its correct position. The first number is the successive number for all entries. The second one which is in parenthesis shows that the number either belongs to the original text, or is added (by a plus sign) from a supplement. The abbreviation and the following PAGE/NO shows the page number and the entry number of the supplement from which the entry is drawn.

Named Entities

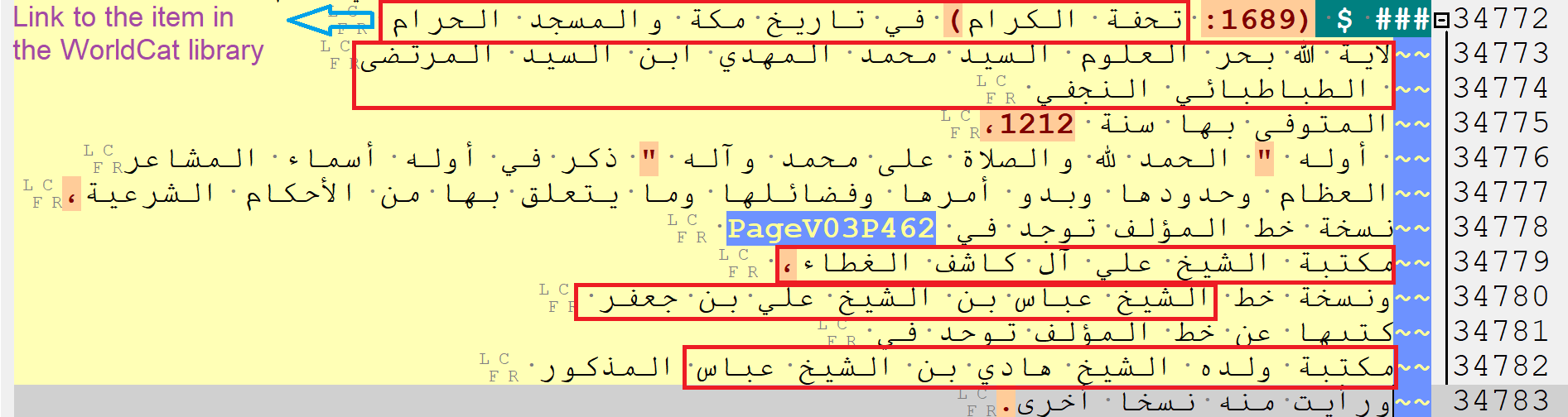

Preparing the text’s indexes (list of the names of people, places, etc.) will be greatly facilitated through this tagging method. Since Arabic keyboards are not uniform and often use different Unicode codes for the same letters, the first step in preparing indexes is to homogenise the letters (this is required since many of the large texts are typed by several typists, or produced by joining sections from different sources). The next step is tagging the names inside the text through a combination of automatic tagging and human annotation (Ideally, tagging the information inside the texts will be part of the project’s analytical annotation phase which should be done according to individual researchers’ objectives. However, given the limitations in resources, this may take years). The text in question here, for example, is much more than a bibliographical collection, and in many cases, presents very useful information about the authors of the entries, or sometimes even the scribes of the manuscripts of the entries. Besides, the name of an author may be repeated several times in the text. So, the name of each person should have an in-text link showing in a pop-up window all the other places where that name appears in the text. This would allow the readers to have quick access to all the books written by each author and also his biographical information in case it is available in the text (the indexes that have been prepared for texts, sometimes published separately, can be used as a base here. See an index of names for al-Dhari’a here for example). If the author is well-known, a link to EI2, EI3 or any other modern encyclopedia, or name authority files (like VIAF) can complement the collection of the links in the pop-up window; otherwise, the links will be a good starting point for collecting information about less well-known authors or even the scribes. Besides, tagging other names in the text will also provide a great opportunity for scholars who will work on different aspects of the text. As an example, in many cases, the author mentions the names of the libraries in which he has found the books he introduces. Tagging the names of the libraries will enable the scholars interested in the history of libraries in Islamic world to reconstruct the lost stock of the libraries to some extent. Furthermore, the entries that have been published up to now can be linked to their respective items in the WorldCat database. This will allow us to have a list of the books that are lost, or are extant but have not been published yet.

Figure 5: Items need to be tagged for producing a comprehensive index, marked with red rectangles.

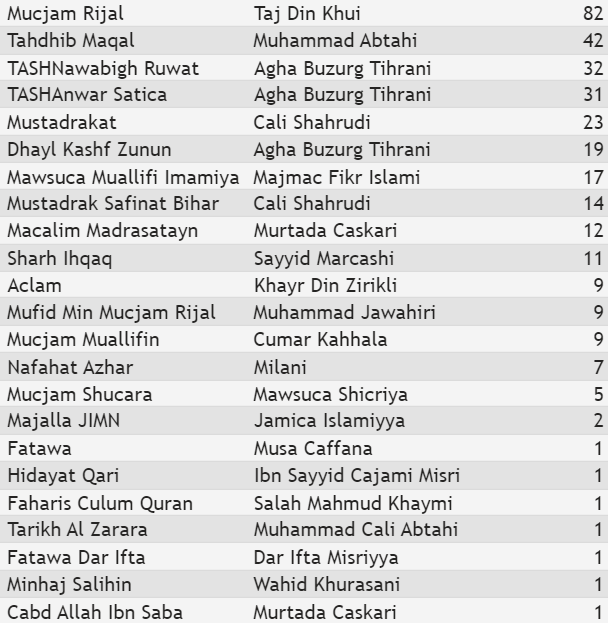

Text Reuse Data

The KITAB team’s text reuse data could enrich an enhanced digital version. The team uses the passim algorithm to compare all texts in the corpus with each other and find instances where a pair of texts have passages in common. This data could be used to find out which parts of the text are drawn from previous texts and which parts are repeated in subsequent textsa process which not only helps in any research about the text, but also in editing the text or reconstructing its lost sections (see Figure 6). Since large texts are more likely to extensively quote previous sources and be quoted in later sources, running passim on them will most probably bring very helpful results (for a general description of passim see here. There are some other blog posts on our website about it: 1, 2, 3, 4).

|

Figure 6: A list of 25 texts written by authors who died before Agha Buzurg for which passim has detected the most cases of text reuse with al-Dhari’a on the left, and a list of the texts written by authors who died after Agha Buzurg for which passim has detected one or more cases of text reuse with al-Dhari’a on the right (the columns on the right side of both lists show the number of instances of text reuse between the text and al-Dhari’a).

Figure 7: Graphical representation of the sections of al-Dhari’a that are reused in all the texts on the corpus written by authors who died before and after Agha Buzurg. Darker colours signify more cases of text reuse in that section of the text.

Passim can also be run on a pair of texts to find similar passages. Figure 8 is the result of passim on the pair al-Dhari’a and Muntajab al-Din Ibn Babawayh’s al-Fihrist, another Shiʿi bibliography written in the 6^th^/12^th^ century, showing which parts of al-Dhari’a are likely to be drawn from this text.

Figure 8: A list of the sections of al-Dhari’a that are taken from Muntajab al-Din’s al-Fihrist based on the milestone IDs of the two texts.

Figure 9: Graphical representation of the information in Figure 8, showing the distribution of the reused passages of al-Fihrist (on the bottom) in al-Dhari’a (on the top). As it is evident, the cases of reuse are very sparse in comparison with the texts at the top of the table in Figure 6. However, for a detailed analysis of the text, they could still be of importance.

After finding similar passages in a pair of texts, it will also be possible to observe the differences between them using our text-comparing app OpenITI Diff viewer (see Figure 10). The app can also be used for a second function. The OpenITI corpus contains different digital versions of the same texts sometimes different digitisations of the same paper edition, and sometimes of different printed editions. Thus, most folders contain more than one edition of the text (this is not the case about al-Dhari’a which is a recent compilation most of which was published while the author was still alive). So, the app also enables specialist scholars (those who intend to present a newer edition of the text, for example) to compare different printed editions and easily observe the differences between them. This will save a lot of time and energy that close reading of the texts for comparison would require.

Figure 10: Using OpenITI Diff viewer app to compare a paragraph in Al-Dhari’a with the corresponding paragraph detected as a text reuse case in Muntajab al-Din’s al-Fihrist (the fifth case in Figure 8).

Last of all, let me emphasise again that the issues considered here are the most typical issues that can be enhanced in the digital versions of all large biographical/bibliographical texts. For an enhanced version, almost all such texts have a numbering system that need to be corrected; have categorised headers (usually alphabetical) that should be revised; have some supplements, written either by the original author or by the subsequent authors, that need to be integrated into the text (many of the supplements are also available on our corpus and are ready to be used for this purpose); need indexes and in-text links that are vital for mining the information inside the text (which can be prepared by tagging the necessary items inside the text by specialists); need to be collated with other editions through digital methods; and need to be set against preceding and following texts to discover which parts of their information is abstracted from previous sources and which parts are reproduced in subsequent texts. The tagged texts in OpenITI corpus, although not necessarily aimed at resolving all of the mentioned issues, provide an unequalled facility which paves the way for scholars and specialists in the field to deal with each one of them. Highly ambitious projects might go far beyond this. In this case, for example, it would not be far-fetched for a team of specialist researchers and editors to embark upon performing the same process on other Shiʿi bibliographical collections on the corpus, as al-Fihrist by Shaykh Tusi (d. 460) or al-Fihrist by Muntajab al-Din (d. 575), aiming finally at creating the most comprehensive Shiʿi bibliography by joining all the collections together. The whole point is that the same process can be carried out on any other biographical/bibliographical collection (or set of collections) in the corpus in any given field.