Running the passim algorithm on the OpenITI corpus allows us to identify a vast number of instances of text reuse, but the quality of these results from a historical point of view depends on the quality of the texts in the corpus. As the material was pulled from various, often inconsistently formatted digital corpora (mainly Shamela, al-Jamiʿ al-kabir, and Shia Online), the text quality of the books in our corpus needs to be properly assessed and harmonised as much as possible. One of our responsibilities as postdoctoral fellows with the KITAB project is evaluating the quality of a number of such texts as well as tagging their general structure. In this blog post I discuss some complexities of this job, especially as they relate to the larger research questions of text reuse, the many-sided ‘inter-’ and even ‘transtextualities’ (Gérard Genette) in our corpus and what we jokingly refer to as the rabbit holes you can fall into when doing this work.

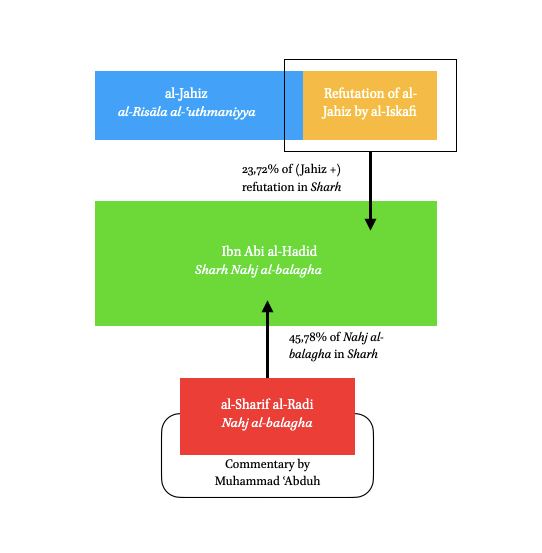

Some time ago I decided to work on the annotation of al-Risala al-ʿuthmaniyya, a text on the virtues of ʿUthman attributed to the early Islamic polymath al-Jahiz (d. 255/868–9). In doing so, I found out that this particular text had been published as part of a compilation that also included an appendix containing a refutation of al-Jahiz’s arguments by his contemporary Jaʿfar al-Iskafi (d. 240/854). To complicate matters further, this other text is in fact only known to have survived through being quoted in Sharh Nahj al-balagha, a large-scale ‘commentary’ on the earlier Nahj al-balagha (‘The peak of eloquence’). The refutation found in our edition of al-Jahiz’s al-Risala l-ʿuthmaniyya is thus an extract tacked on by a modern editor and does not reflect the historical transmission of al-Jahiz’s text.

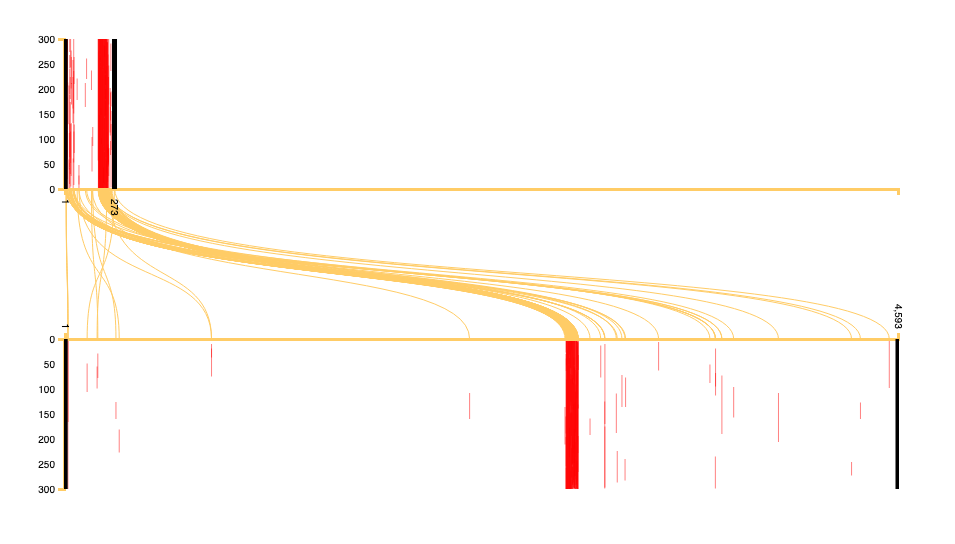

Nahj al-balagha itself consists of various sayings, sermons and speeches attributed to ʿAli b. Abi Talib (d. 40/661), who was widely appreciated as having been extremely eloquent and well-spoken (i.e. baligh). Its compilation is generally attributed to al-Sharif al-Radi (d. 406/1016, but in our corpus it is still filed as a work by ʿAli b. Abi Talib himself. The later Sharh Nahj al-balagha was compiled by the seventh/thirteenth-century scholar Ibn Abi al-Hadid (d. 656/1258) and has become arguably even more popular than al-Radi’s text. This popularity may be explained through the particular predilections of ‘post-classical’ Arabic literary tastes: Ibn Abi al-Hadid not just commented on the lexical and semantic meanings of various words and phrases but also took the occasion to display his vast knowledge of the Arabic written tradition. This resulted in twenty volumes of associative digressions on matters of poetry and literary theory, and also on some doctrinal issues – it is interesting to note that the work of Ibn Abi al-Hadid, who belonged to the Shafiʿi madhhab, cuts across doctrinal divides and remains popular amongst both Shiʿis and Sunnis. It is in these digressions that we should locate the quotations from Jaʿfar al-Iskafi’s refutation of al-Risala al-ʿuthmaniyya, which Ibn Abi al-Hadid deemed relevant to include. In the visualisation of text reuse between the digital version of al-Jahiz’s al–Risala al-ʿuthmaniyya (top) and that of Sharh Nahj al-balagha (bottom) below, one can see that the correlation of the texts is mostly comprised of one chunk near the end of the first work (i.e. the appendix containing al-Iskafi’s refutation), which is unsurprisingly found more or less verbatim in the second work (in the thirteenth volume, to be more exact), as well as a smattering of other material throughout the work.

Image 1: The top of the graph represents the digital version of al-Jahiz’s al-Risala al-ʿuthmaniyya, the bottom the digital version of Ibn Abi al-Hadid’s Sharh Nahj al-balagha. Red lines denote the chunks of text shared between the two texts, while the yellow lines show their positions within the works.

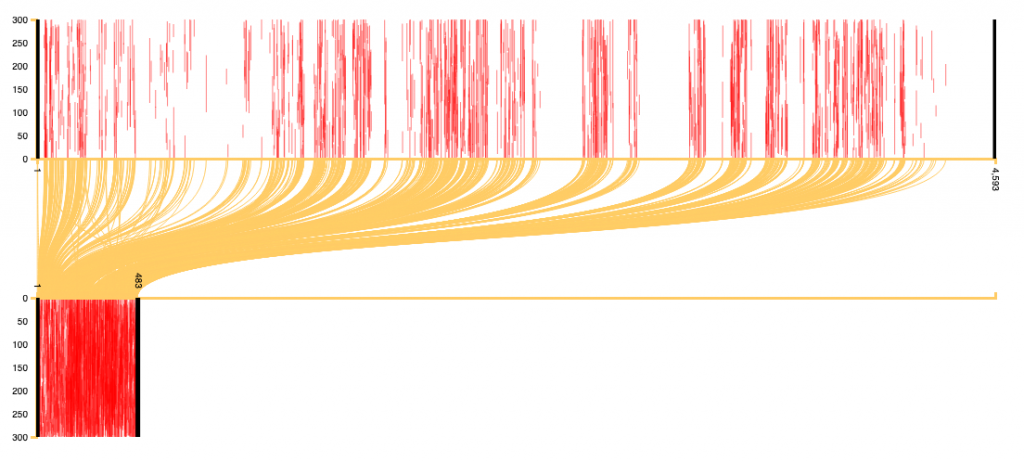

Below is a visualisation of the relationship between Ibn Abi al-Hadid’s work and the work it comments on, Nahj al-balagha:

Image 2: The top represents the digital version Ibn Abi al-Hadid’s Sharh Nahj al-balagha, the bottom the digital version of the much shorter Nahj al-balagha. One can see that material from the Nahj al-balagha is found all across the Sharh, as would be expected in a commentary, though with several fairly large gaps, which are likely caused by Ibn Abi al-Hadid’s extensive digressions.

The most surprising aspect of this visualisation is that the original Nahj al-balagha does not seem to match fully with the Sharḥ — this is clear from the fact that the red block of text that represents Nahj al-balagha is not fully coloured, as one would expect if we’re dealing with a word-for-word commentary. If we look at statistics on word match between these two digital works, it appears that the Sharh includes only 45% of Nahj al-balagha. Does this mean that Ibn Abi al-Hadid commented on only about half of the original text? Having gone through the entirety of Ibn Abi al-Hadid’s twenty volumes, this struck me as unlikely, so I took a closer look at the digital version of Nahj al-balagha. It turns out that when the digital version of this text had been prepared for the OpenITI corpus, the footnotes had not been successfully deleted. However, in a way this was somewhat fortunate, as these footnotes add another layer of beautiful complexity to our case: the footnotes consist almost entirely of another commentary on this text by none other than Muḥammad ʿAbduh (d. 1905). It is interesting to note that ʿAbduh’s commentary is much drier and to the point than Ibn Abi al-Hadid’s is and resembles much more our modern use of footnotes, an obvious shift in audience tastes for this kind of material. It could be argued that this digital text thus preserves not one but two texts, albeit in a completely different way than in the earlier example of the Risala al-ʿuthmaniyya, in which the editor simply tacked a commentary on to the end. The editor of this version of Nahj al-balagha, by contrast, included the commentary in a way that is reminiscent of practices common in later periods of the Islamic written tradition, namely with marginal and interlinear commentaries, which do not easily translate to the format of a modern edition.

Cases such as these create complexity in our corpus that we have to address and distinguish thoroughly if we want to create reliable data on text reuse. We have recently taken a number of decisions to resolve problematic cases such as these: in the case of books containing more than one text we have decided to transfer the additional texts into separate files and to convert residual footnotes into endnotes, which can then be excluded for certain types of analysis but preserved for other types. Of course, even when our data becomes ‘cleaner’, qualitative assessment will always be needed. At the same time, problems such as these also highlight the vibrant complexity of the Arabic written tradition itself and provide food for thought and discussion for the general research angles of the KITAB project.

Image 3: A general visualisation of textual relationships in this case study.