Researchers working on historical Arabic texts have long known about transmission practices that resulted in considerable differences between what were ostensibly versions of the same work. Scholars transmitted their works to many students and sometimes over long time spans; works were transmitted differently in terms of wording, structure and scope of contents. The afterlife of texts played a role too. Witness copies were dispersed over great distances. Parts were extracted and rebound with other texts. The result is that today’s print editions often produce an ideal text that never, in fact, existed.

But just how much was the tradition in flux? Now that thousands of print editions have been converted into machine-readable format, we are beginning to have more of an idea as we can compare different versions mathematically and algorithmically (conversion to machine-readable formats has also produced its own problems; more on this below).

A major task for the KITAB team is to work out just how much variation there is in titles. We have been doing this by comparing our text files to scanned versions of editions and, in some cases, physical books and recording differences in our GitHub repository (Table 1).

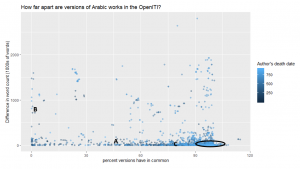

Table 1: The KITAB annotation team records issues while annotating texts. This work informs which version is labelled the ‘primary’ version in our corpus. Our statistics on corpus-wide text reuse rely on primary versions only.

This sort of close reading of texts will remain critical to understanding variations and to making corrections to machine-readable files to bring them into line with the print editions upon which they are based. But now we have also added a method that relies on word counts and the text reuse algorithm passim to provide another sense of how related our versions are at scale.

The method: Evaluating differences at scale

The method for detecting differences in versions at scale can work for both cleaning of the data and, ultimately, the deeper analysis of transmission practices.

We start now with the cleaning. We have spent a lot of 2019 evaluating passim results and have found the February 2019 run to be, so far, our best. We used the data from this run, which included all versions of the texts in the corpus. We extracted data to compare 3,215 textual versions, representing 1,552 titles. We have texts in single versions and others in multiple versions; all were compared. We also have single versions of texts in our corpus that do not form part of this data set.

Our first look at the data shows the following:

- Comparing word counts across the centuries (specifically, years 1–911 AH), we find that the median length difference between versions is 1,559 words. That is shorter than this blog post and can arise rather easily even between two nearly identical versions. The mean length difference is 78,683 words, which reflects the distorting effect of outlier cases. To give a sense of these outliers, the largest length difference was 2,799,758 words – in a case in which a title was applied to both a part of a work and the work itself.

The median is the more important number for reckoning the general state of the corpus, because it represents the middle value of the data set (i.e. the case of any specific comparison at least half of the time). Still, the mean alerts us to the degree to which many titles are not represented by the median.

- Comparing the percentage of words matched across the centuries reveals that the median is 96.17% for the wording in Version 1 aligning with that of Version 2, and 96.1% for the wording in Version 2 aligning with that of Version 1. The means, showing the downward pull of outliers, are 87.79% and 87.25%, respectively.

We can also consider this data on a per-century basis.

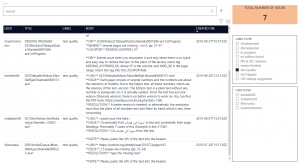

Image 1: A boxplot graph showing the degree of matching between different versions of a work across the centuries.

Image 1 provides century-level detail on our words-matched statistics. The yellow boxes represent the degree of matching in version pairs that fall between the twenty-fifth and seventy-fifth percentiles (the interquartile range), with the black horizontal line representing the median for each century’s versions. The horizontal lines below and above each box represent the minimum and maximum values, respectively. The circles below the boxes represent outlying cases. In 163 cases, the alignments equal or exceed 100% because of internal reuse within a text. This happens when one part of Version 1 matches two parts of Version 2, or the reverse. The bars above 100% mark reflect this situation. It is worth noting that we also lose reuse data at the boundaries of text chunks. We are working to improve our calculations.

Whichever way we look at the data, the median words-matched numbers indicate rather precise alignments between versions.

The outliers

Then there are the outliers.

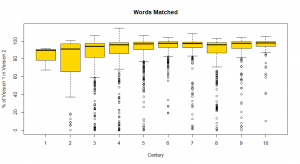

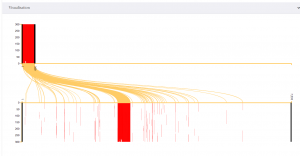

Image 2: A graph based on the same versioning data. The circled area in the visualisation represents 2,061, or 64%, of the comparisons of versions. The other 36% of compared version pairs show sharper – and sometimes very sharp – differences.

Each dot in Image 2 represents a case in which we have ostensibly two versions of the same work stored in GitHub.

Consistent with Image 1, the greatest concentration of dots is toward the bottom right. Within the circled area, the two versions differ little in word count (the y-axis) and have at least 90% of their words in common (the x-axis). In 2,061 out of our 3,215 comparisons, version 1 matched the second version by at least by 90% and with no more than 50,000 words differing.

Both graphs show us outliers that require attention, though in different ways. The first breaks the data down by century and gives the sharpest picture of the median. The second provides the clearest view of the outliers. Within the KITAB team, we are working with a dynamic version of the second graph that helps us prioritise outliers for attention.

Examples

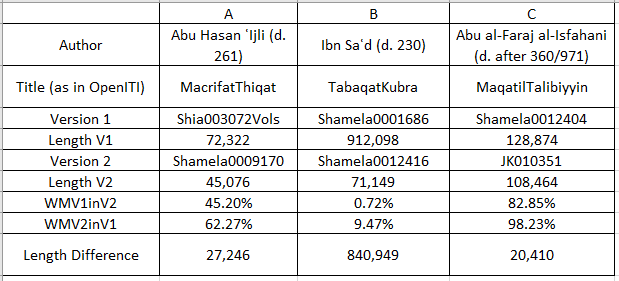

But what are these outliers – the texts whose versions differ significantly? As examples, let us consider three situations, labelled A–C in the table below, which summarises the relevant data:

Table 2: Differences within pairs of versions of three different works – Abu Hasan ʾIjli (d. 261/874-5), Ibn Saʿd (d. 230/845) and Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani (d. after 360/971).

These might be fairly typical cases. A quick reading of the files on GitHub shows the following:

-

The correct title of version 2 of the first text, Shamela0009170, is not Maʿrifat al-thiqat but rather Taʾrikh al-thiqat, another work written by the same author.

-

Version 1, Shamela0001686, of the second text, Ibn Saʿd’s al-Tabaqat al-kubra, is a complete version of the work; version 2, Shamela0012416, includes only parts of it. The metadata gives the title as الجزء المتمم لطبقات ابن سعد. الطبقة الرابعة من الصحابة ممن أسلم عند فتح مكة وما بعد ذلك.

-

Version 1, Shamela0012404, of the third text is based on the undated Beirut (Dar al-Maʿrifa) edition of Maqatil al-Talibiyyin prepared by al-Sayyid Ahmad Saqr and contains the editor’s introduction and footnotes, whereas version 2, JK010351 (for which there is no metadata), does not contain these.

Some of these cases represent errors that are rather easily identified and remedied. In our first reading of the data, for example, we identified 618 cases, involving eleven titles, where we had very little overlap between two versions because one of them represented a small excerpt of the larger text. They were filtered from the data described above and are not represented in the graph. This rather common scenario shows up in the percentages with the smaller work having a high percentage matched and the larger work having a small percentage matched. A text file with the identifier Shamela0023678, for example, was listed as Ibn Kathir’s Bidaya wa-l-nihaya; however, the 107,574-word text is in fact excerpted from the Bidaya and labelled in the text file as Muʿjazat al-Nabi. When we used passim to compare this excerpt against twelve versions of the Bidaya, each of which was about 2 million words long, we found the ‘versions’ to be very distant. So we need to make sure our data accounts for the fact that the short text represents only a part of the work, not the entirety of it.

When we align two books using one of KITAB’s data visualisations, we can often see what is happening. By way of example, see below:

Image 3: The top of the graph shows the short ‘version’ of Ibn Kathir’s Bidaya wa-l-nihaya (Shamela0023678), with the text, in 300-word chunks, running along the x-axis. The bottom shows a longer version (Shia003593Vols), also chunked in 300-word segments. The yellow lines represent alignments between the two texts. The scattered red lines in the bottom part of the graph likely indicate that the longer version is itself repetitive and matches more than one part of the short text.

So why – in sum – do versions differ?

Many of the numeric differences arise from the transition to machine-readable format. The problem here lies not, in the first instance, in the precision with which the texts were typed up: so far, we are finding the typing to be generally highly accurate (even when pages are missing, the typed text corresponds verbatim – and it is worth noting that the missing parts seem random and the result of simple human error).

To deal with one type of digital-born error, we ran scripts to remove footnotes, but these were only partially successful. As the KITAB team annotates the book files, team members are marking editorial information (such as introductions) for removal, plus adding missing numbers and text using the scanned images. We record these errors/improvements in a file on GitHub (all have the extension .yml; Image 1 above represents a collation of these files through Power BI software).

Somewhat more schematically, the following factors seem to explain the major differences encountered between versions so far:

-

Misattribution – the compared works are not in fact versions of one another but entirely different works (situation A in Table 2 above).

-

Application of the same title to a shorter text as well as a longer one that includes the smaller piece (situation B). This happens under a variety of circumstances, including with anthologies, or when a part was printed separately (possibly on the basis of manuscript evidence), or when a large text was typed up in separate files.

-

Inclusion vs. non-inclusion of introductions, footnotes, editor’s tables, indexes, etc., all of which should be stripped out (situation C).

-

Missing paragraphs or pages.

-

The inclusion vs. non-inclusion of chains of transmission for Hadiths and historical reports.

-

Inclusion vs. non-inclusion or abbreviation of pious formulae and the presence of spelled-out dates versus those written in numbers.

-

Separation of parts of a text – volumes published separately, for example.

-

The presence of commentaries within, alongside or following a text.

In cleaning our data, issues 1, 3 and 4 are rather straightforward to deal with – we can relabel works, strip out modern editorial material and, wherever possible, consult editions to type up missing content. Issues 5 and 6 explain differences but require no intervention from the annotation team (we do not aim to improve editions). Within the span of our ERC grant, we should be able to identify and address these issues for a significant number of our texts, vastly improving the quality of our corpus.

Issues 2, 7 and 8, however, are more complicated. They raise legitimate questions about what within the Arabic tradition is reckoned to constitute the text properly speaking. This is both a practical and a philosophical question. Practically, we can check title pages and even go back to the manuscript tradition. On this basis, one might reckon the longer version to be the ‘text’ and the shorter one a derivative.

Versions as a major topic for book history

To return to the point made at the start of this post.

In our cleaning, we should be careful. We should not be looking for ideals of texts that never existed. Our partial versions may not be simply modern derivatives. For example, in the case of the Bidaya wa-l-nihaya, all surviving manuscripts of this great classic of Arabic letters are only partial witnesses to the text. Perhaps the most complete version originally consisted of eight volumes, of which substantial parts are missing. This suggests that a partial version may be more faithful to how the text was experienced historically.

We can also ponder what the print tradition represents of the manuscripts upon which it is based. We can imagine alignments of machine-readable files based on manuscript witnesses to a specific text. The files are generated either by transcription or by human-corrected Optical Character Recognition. We can visualise differences and compare the manuscript-based files with existing print editions.

We need to work on cleaning our data. But our work will not stop there. We should use our data to consider the general picture of parts of works that over time come to be experienced as the work, or of variation within the tradition in general. Does closeness between versions change over time? Are third/ninth-century versions less close than ninth/sixteenth-century ones? What about genres? Do we find more variation in some corners of the Arabic tradition than in others? Does excerpting increase in particular times and places and/or with particular genres?

With mathematical reading at scale, these are the sorts of provocations that will make work in the Digital Humanities exciting and worthwhile.

N.B. This post was written on the basis of data generated by the KITAB technical team (Masoumeh Seydi, Ryan Muther and Sohail Merchant) and following many discussions with team members working on the corpus, especially Maxim Romanov, Gowaart Van Den Bossche, Mathew Barber and Peter Verkinderen. I used the programming language R for the statistics and for Images 1 and 2. There are many reasons that this topic matters. Other posts on versions will follow.