The OpenITI corpus is designed to facilitate many different forms of computational analysis. Within the KITAB project we spend the bulk of our time fine-tuning the methods of text reuse and the data it provides on the corpus’ many textual relationships, but we are aware that this is not necessarily the primary interest in digital texts for many scholars. As the continued popularity of the Shamela library and its software suggests, one of the most important functions of a corpus of digital texts is its searchability: scholars want to be able to search for information and locate the usage of names, words and phrases across a vast corpus. In the long run we hope to develop a complex search app by which users will be able to search the OpenITI corpus online, but our colleague Aslisho Qurboniev discovered that doing so is in fact already possible with both of the two text editors we recommend to read texts from the corpus: EditPad Pro and Kate. This is a great and easy method to do searches and it is more reliable than using Shamela. For guidance on installing these editors and the mARkdown highlighting scheme, see here. (Installing the highlighting scheme is not absolutely necessary for simply searching the corpus, but it is nice to be able to fold texts and see the structural tagging to help navigation.)

In this blog post I will explain the method for doing this kind of search in Kate, as this text editor is available for free and functions well on both Mac and Windows. Its only disadvantage is that loading large files takes a little while, and sometimes temporarily freezes the app. The EditPad Pro method follows a similar process and is explained briefly in an appendix at the end of this blog. In the second part of the blog I briefly zoom in on some search results I have come across by using this method for the phrase ‘ikhwan al-safaʾ’, which was famously used by an enigmatic early scientific and philosophical community who wrote a compendium known as the Epistles of the Pure Brethren (Rasaʾil ikhwan al-safaʾ).

Searching the corpus with Kate

To do a search on the OpenITI corpus using this method, it is necessary to download the OpenITI corpus onto your computer. The easiest way to do this is by downloading one of the fixed corpus releases we release twice a year. The most recent release can be found here. Please note that the current release will take up five gigabytes on your hard drive. With further releases this will likely increase as the corpus is ever expanding. We are also thinking about doing a separate release with only primary texts (that is, no secondary versions of the same text) in the future. For your own convenience it will be best if you move the folder to an easily retrievable location after downloading, for example in your Documents folder.

If you download the OpenITI corpus as a release, all author files will be in a single folder (and not subdivided into quarter centuries like on GitHub) with their books included in their respective subfolder. You can simply direct EditPad Pro or Kate to search through the general OpenITI folder and it will then take into account all these subfolders. If you are interested in the uptake of words and phrases in a particular period, you could create a specific subfolder and copy those texts that fall within that period into a separate folder and direct the text editor to search through it instead of the whole folder. Alternatively, you could also simply download individual text files or 25 year folders you are interested in directly from GitHub and save them in a folder to create your own subcorpus.

Once you have downloaded the corpus, launch the Kate app, click the 'Search and replace' tab, which in Image 1 below is on the bottom left of the app (or use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+Alt+F on Windows = Cmd+Alt+F on Mac). This will open a dialog box in which you can change the location where Kate will conduct the requested search: either in ‘current file’, in all ‘open files', or 'In Folder'. It is this last option we will use to search through the whole OpenITI corpus.

Image 1: The basic search window in Kate editor

Once the 'In folder' option has been marked, you only have to tell Kate where the folder you want it to look through is situated on your computer. For this you click the folder icon next to the Folder bar (see Image 2), which will open a pop-up where you can direct your computer to where you have stored the OpenITI folder. This should be a familiar procedure if you have ever opened a file from within a text editor like Word or added an attachment to an email

Image 2: Second step of the search in Kate editor – directing Kate to the relevant folder

That’s all! The next step is simply typing your search term or phrase into the 'Find' bar and clicking 'Search'. Kate will then search through all the files contained within the OpenITI folder and list any results which you can then review individually. Due to the amount of files to search through it will take a few minutes to complete, so a perfect time to go and make yourself a cup of coffee.

Kate will list all results, ordered alphabetically (which means chronologically due to how we name files in the corpus). It is possible to copy these results and paste them in a separate document: this will copy the filepath and the line number as well as the place where the result is found, but the results will not be clickable. In EditPad Pro you can do the same, but the result will be clickable. Once the results are displayed (see Image 3), you can click on one of the results and Kate will open the file and take you to the place where the search result is found in the text by highlighting it. As with Shamela, the search via Kate or EditPadPro is not as smart as Google or the passim software we use to detect text reuse. It will not locate words spelt differently than the way you have input it. The inclusion of works digitised by using OCR in newer releases of the corpus, many of which have not yet been closely proofread, as well as the preponderance of typos in texts from online libraries should also be taken into account. It thus remains important to closely check every search result, especially if they come from texts that do not bear the mARkdown tag (although that tag does not necessarily mean a text is entirely reliable or free from typos, only that it has been looked at by at least two different people and its problems/reliability have been assessed). One way to work around this is by using regular expressions (regex), which is useful to learn in general if you are interested in learning some computational skills.

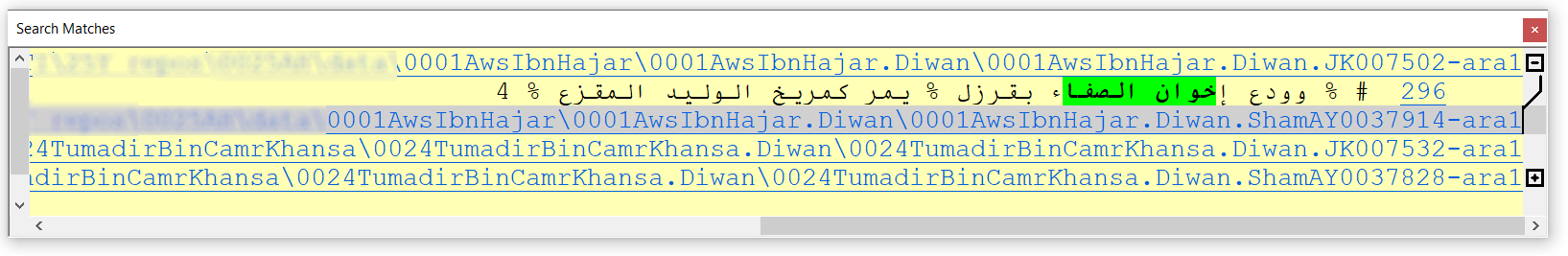

Image 3: 'matches' listed in the search window and highlighted in individual text files.

Searching for the Ikhwan al-safa in the OpenITI corpus

To illustrate the method, in the following I will show a few results on searching for the phrase 'ikhwan al-safa' in the corpus. Because of the ambiguity of whether or not the digital texts have properly spelt the first and last letters of that phrase with their respective hamzas, I omitted them and told Kate to look instead for 'khwān al-safa' (see image 3). Regex would have helped here to also include cases where the two words are separated: if the space in the search term is replaced with the regular expression [ -\r\n]* it will deal with cases where 'ikhwan' and 'al-safaʾ' are separated by a new line, page number, footnote marker and/or milestone number, etc. but not by another Arabic word. (I am grateful to Peter Verkinderen, KITAB’s in-house regex wizard for this advice).

As is clear from the search results and, to be sure, as is well known among scholars the phrase 'ikhwan al-safaʾ' did not originate with the enigmatic brotherhood that composed the Epistles. They made use of an existing turn of phrase to designate themselves as a brotherhood that saw itself as exceptionally pure and sincere and which strove to create a broader community built around those principles. Some scholars have suggested that the authors of the epistles took the phrase from Kalila wa-Dimna (notably Ignaz Goldziher), which seems plausible enough given that the epistles refer to Kalila wa-Dimna repeatedly and reproduce some of its stories. Our search results indicate however that the translator of Kalila wa-Dimna himself likely made use of a phrase that was already well attested as a poetic trope and that the authors of the epistles may also have been more broadly inspired. In Image 3 I have opened the earliest search result, a diwan (poetry compilation) of the pre-Islamic poet Aws b. Hajar (he in fact died before the Hijra, year 1 in the OpenITI corpus, but all pre-Islamic authors are filed under that year within OpenITI), which contains a poem in which the phrase is used. In general, results from the earliest centuries need to be interpreted with care as many of these texts are problematic reconstructions. Some of these diwans never even circulated as such in the pre-modern period and are modern compilations. The early transmission history of Kalila wa-Dimna is also all but straightforward, however, as the work of the AnonymClassic project is showing. Nevertheless, it appears that the phrase had some currency already very early on and that the authors of the epistles may have been inspired not just by Kalila wa-Dimna but by a relatively broadly circulating metaphoric designation.

Another very early instance of the phrase, which for sure predates the encyclopaedia and likely also Kalila wa-Dimna, is found in Ibn Hisham’s redaction of Ibn Ishaq’s sira of the Prophet. Here the phrase is used in a poem attributed to Abu Khurāsh in which the death of one of the fighters at the Battle of Hunayn is lamented (PageV02P474 of the file 0213IbnHisham.SiraNabawiyya.Shamela0023833-ara1.completed). A very similar phrase is found in a poem that has been attributed to ʿAli b. Abi Talib (see below).

While I could write much more about the many different results I found, I will in the remainder of this blog continue to focus on a few further poetic usages. Such references are an understudied phenomenon which I believe has great potential for the study of the reception of the Ikhwanian corpus. Coming across one such poetic use initially urged me to conduct this search: on an important 7th/13th century manuscript manuscript of the Rasaʾil ikhwan al-safaʾ a reader wrote a line of poetry the flyleaf (see Image 4).

Image 4: poetic line on flyleaf of Süleymaniye Kütüphanesi MS Esad Efendi 3638

As this reader helpfully notes, this line is taken from a longer poem included in the diwan of the famous 8th/14th century poet Safi al-Din al-Hillī (for an accessible introduction to his life and work, see this great podcast episode), a delightful reproach to a friend who had taken offence at something unspecified al-Hilli said or wrote. The poem is not explained or introduced in the diwan but it is fairly easy to understand. Al-Hilli wrote many poems in this genre of ikhwaniyyat which boomed in the Islamic Middle Period when poetic communication became much more diverse and socially horizontal, rather than predominantly embedded in hierarchical court settings. While the diwan does not give any further info about the recipient of this poem, it does not give the impression of being addressed to a superior either. Here is the full poem with my translation, with obvious references to the Epistles highlighted in bold. The line cited on the manuscript fly leaf is the third line. (I am grateful to Lorenz Nigst and Aslisho Qurboniev for their advice on this translation)

حَتّامَ أَمنَحُكَ المَوَدَّةَ وَالوَفا وَتَسومُني قَصدَ القَطيعَةِ وَالجَفا

How I gave friendship and fidelity to you

only to have you impose estrangement and aversion on me

يا عاتِباً لِجَريرَةٍ لَم أَجِنها ظَنّاً بِأَنَّ وَفايَ كانَ تَكَلُّفا

You censured an offence that I did not commit

as if you thought my fidelity was but pretension

بِاللَهِ لِم ثَقُلَت عَليكَ رَسائِلي هَذا وَأَنتَ أَجَلُّ إِخوانِ الصَفا

By God, why do my letters weigh on you

even though you are the loftiest of the Sincere Brethren?

وَلِمَ اِطَّلَعتَ عَلى جِبالِ مَوَدَّتي فَجَعَلتَها بِالهَجرِ قاعاً صَفصَفا

Why did you ascend the mountains of my love

only to make them into a barren wasteland by abandoning them soon after?

هَب أَنَّني أَغلَظتُ قَولي عاتِباً أَيَجوزُ أَن يُقلى الصَديقُ إِذا هَفا

Assuming that I spoke rudely when I scolded you,

does that mean a friend’s lapse gives permission to detest him?

إِنَّ الصَديقَ إِذا تَأَكَّدَ حَقُّهُ بِالوُدِّ أَغلَظَ في العِتابِ وَعَنَّفا

For the friend, if convinced of his right,

will speak coarsely and vehemently in censuring out of affection

وَكَذا سَميعُ العَتبِ في حالِ الرِضى يُغضي لَهُ وَإِذا تَحَرَّفَ حَرَّفا

And just so, he who contentedly hears the censure,

will condone it, even if it is extremely harsh

كَالراحِ تُدعى الإِثمَ عِندَ مَلالِها وَمَعَ الرِضى تُدعى السُلافَ القَرقَفا

Just as wine is called 'sin' (ithm) when people grow weary of it

and a 'vintage' (sulaf) or 'frisson' (qarqaf) when it brings pleasure

The fact that al-Hilli does not just use the phrase ikhwan al-safaʾ here, but also rasaʾili to refer to his own letters leaves little doubt that he is here not just evoking a time-worn turn of phrase, but also a text that had by his lifetime become very popular. As my ongoing research into the manuscript tradition of the Rasaʾil ikhwan al-safa indicates, production notably boomed in the 7th/13th century and most prominently in the Ilkhanid realm and sphere of influence where al-Hilli spent a good part of his life. Furthermore, in the first line he uses the word 'al-wafa', which is found in the longer title of the epistles: Rasaʾil ikhwan al-safaʾ wa-khullan (or khillan) al-wafaʾ. Another search I did for the latter phrase in the corpus indicates that this was much less widely used, and that when it was, it tended to refer unambiguously to the Epistles. However, note that the last word in the line referring to ikhwan al-safaʾ is written defectively as safa (that is, without the final hamza) and thus may refer to the hill of Safa in Mecca. Although I think it is more of a case of poetic licence here, some of the usage I came across in other search results does indicate this second meaning, and al-Hilli is possibly deliberately courting ambiguity here. Indeed, in the fourth line of this poem he also refers to the 'mountains of my love' (jibal mawaddati). This may refer to an exceptionally beautiful poem attributed to ʿAli b. Abi Talib (transmitted amongst others by Ibn ʿAsakir) where he refers to the love amongst the Brethren of Safa whose friendship 'we engraved on the sky with pens of fine dust' (naqashna wudd ikhwan al-Safa // bi-aqlam al-habaʾ ʿala al-hawaʾ).

As it turns out, our poem is also not the only one referencing the ikhwan in al-Hilli’s diwan. He does so again, and much less ambiguously, in the first line of a longer 23-line poem inviting a friend to his house in Mardin (this time the topic is introduced in the diwan), where he writes all the hamzas and also uses the phrase khillan al-wafaʾ:

رسائل صدق إخوان الصفاء تجدد أنس خلان الوفاء

Sincere brethren’s truthful writings

renew the intimacy between faithful friends

This is but a very small sampling of the 1694 matches for our phrase identified by Kate in the OpenITI corpus (see Image 3 however, note that probably at least half of these are duplicates, usages found in two or more different versions of the same text), but it highlights that poetic references to the Ikhwan al-Safaʾ constitute a potentially rich field of enquiry for which this simple search method may be used fruitfully. The existence of a number of versifications of Epistles from the Ikhwanian corpus as well as poems responding to the Epistles’ contents recorded on flyleaves and title pages, which I have come across in my study of the Ikhwanian manuscript tradition suggests that this could figure in a broader evaluation of the literary reception of the Epistles.

Appendix: Searching in EditPad Pro

In EditPad Pro: Use Ctrl+F to open the search-and-replace box, and write your search term in the Search field. In the EditPad Pro menu, go to Search > Find on Disk; this will open a dialog box where you can select the folder you want to search.

Image 5: Search on Disk dialog in EditPad Pro. Pro tip: write `\^[01].+(?<!yml)$` in the Regular expression field, after ticking the ‘regular expression’ box: this way, only text files will be searched, and not metadata or other irrelevant files. (Note, this also works in Kate)

If you click the OK button, EditPad Pro will start searching all files and subfolders within that folder. The search results will finally be displayed in a separate window. You can preview the lines that contain the matches inside the search results window; if you double-click on the line number, the text will open in the editor at that location.

Image 6: EditPad Pro search results