As KITAB’s research has shown, passim is an incredibly powerful tool for answering a variety of questions about book history and history in general. The algorithm produces a huge amount of data, which we can utilise in our research in many ways. At present, we typically investigate text reuse in the corpus at the level of relationships between pairs of books. That is, we look at statistics that tell us what percentage of one book is reused in another and we visualise alignments between two books. This approach is great for understanding how two books are related, but once we start comparing multiple books these approaches become quite cumbersome.

To note a couple of examples: What if we wanted to investigate how one particular book was disseminated across tens or even hundreds of later works? Or what if we wanted to know about how one particular unit of information (perhaps a narrative about a major event) circulated throughout our corpus? To help deal with these kinds of questions the team has been developing new applications for understanding multiple-book relationships. In this blog post, I will take the opportunity to introduce some of the applications under development. To do so, however, requires a short tangent on bioinformatics.

The computational analysis of text reuse has developed and advanced alongside that of genomics. This is a fact noted explicitly by David Smith, when he acknowledges that passim utilises the Smith-Waterman alignment algorithm, which is also used in the analysis of genes.1 Text reuse and genetics are both concerned with problems in sequencing. Put simply, when biologists wish to analyse genes, they convert genetic material into a sequence of letters (A, C, G, T), each of which represents a chemical nucleotide base (adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine). Three-letter words termed ‘codons’ specify the amino acids that are used by the body to build proteins.2 There are also ‘stop codons’ that mark the end of the sequence. Similarities in sequences of letters between parts of a chromosome or with other chromosomes, or even similarities between the genomes of different animals, might indicate (for example) similar biological functionality. In short, important biological questions can be resolved by identifying similar sequences of letters, and alignment algorithms such as Smith-Waterman are used to undertake this task.

The computational processes used to identify genetic alignments and textual alignments are, therefore, shared. It is natural, then, that we should look to the field of genomics for inspiration when thinking about and visualising text reuse, too. We could, for example, think of books as analogous to genomes and chapters or volumes as analogous to chromosomes. Just as biologists annotate particular parts of DNA that correspond to a particular biological function and then look for alignments in other, unexplored parts of DNA, we might annotate part of a text (for example, information corresponding to a particular topic) and look for alignments in other texts. Therefore, to explore text reuse data, we do not need to necessarily build applications from scratch. Whole suites of applications have already been developed to aid biologists in reading and annotating genetic alignments. Although not all of these tools are immediately useful for the study of text reuse, there are parts that we could adapt, particularly for comparing relationships between multiple books.3

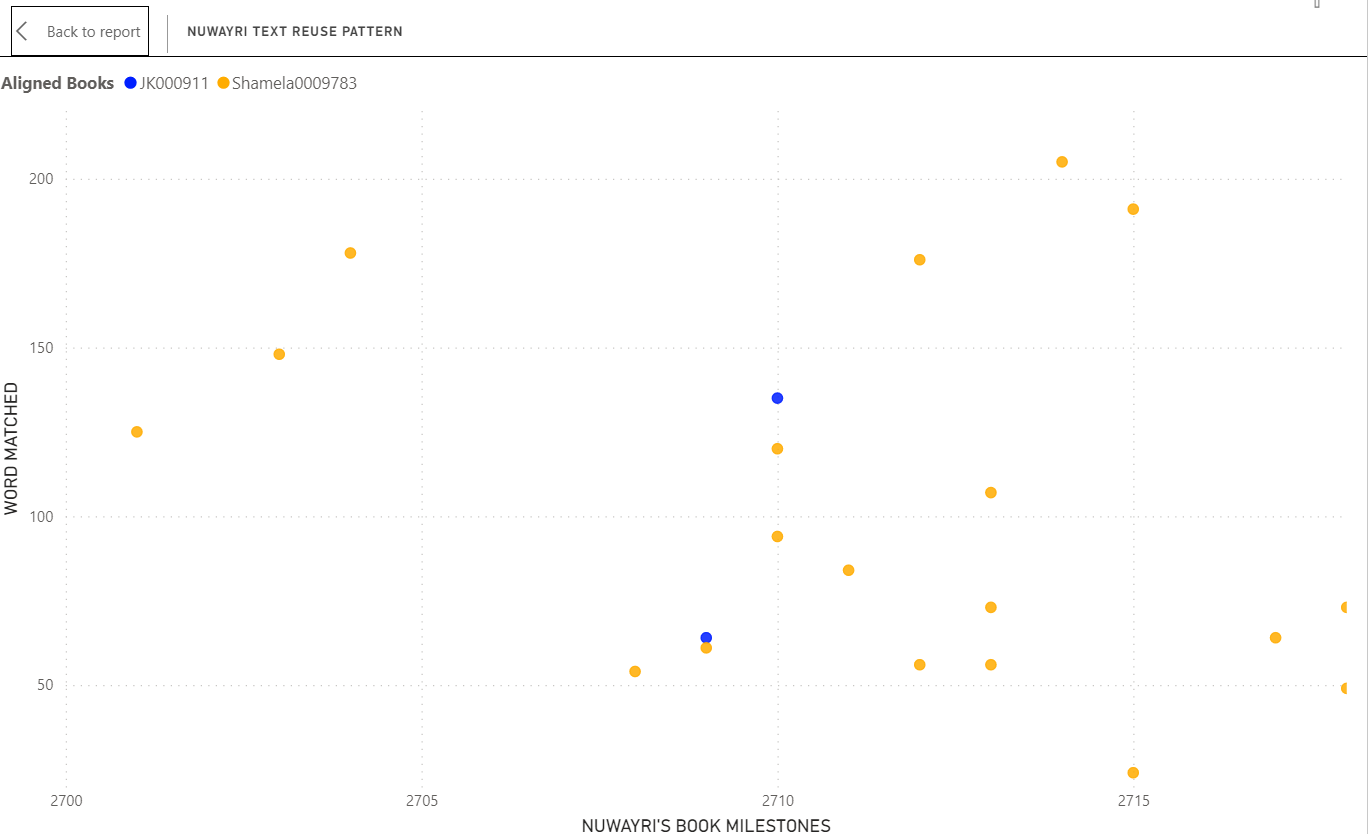

The team’s first foray into visualising relationships between multiple books uses Microsoft’s Power BI and was developed to investigate the multiple texts used in one book, al-Nuwayri’s Nihayat al-arab, in a collaboration between Sohail Merchant and Sarah Savant. In particular, Sarah was interested in prising apart overlapping sources. For multiple milestones – that is, the 300-word chunks into which we divide our texts – al-Nuwayri’s text aligns with al-Tabari’s Taʾrikh and Ibn al-Athir’s Kamil. As Ibn al-Athir also reused al-Tabari’s text, it is necessary to separate his quotations of the text from al-Nuwayri’s. To investigate these questions, the application gives a scatter plot with the milestones of the main text (in this case the Nihaya) on the x axis. We then plot onto the graph a dot for every case in which passim found text reuse for a milestone on the x-axis, giving the number of words matched on the y-axis. For example, if milestone 2711 in the Nihaya had text reuse with al-Tabari’s Taʾrikh with eighty-four words matched between the two milestones, then a dot would be plotted for that text at location 2711 on the x-axis and at 84 words on the y-axis. Filters allow the user to set thresholds for how closely the milestones should align (by number of words matched and percentage of alignment matched). It is also possible to filter by author or title to explore how particular books are reused in comparison to others. For an example, see Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Al-Nuwayri’s Nihaya as shown in the Power BI application, filtered to show only al-Tabari’s Taʾrikh (in orange) and Ibn al-Athir’s Kamil (in blue). One can clearly see a few cases in which the Nihaya aligns uniquely with the Taʾrikh. However, in many cases in which a milestone is shared by both the Kamil and the Taʾrikh, more words match with the former, suggesting that the Kamil is being used in preference to the Taʾrikh.

Figure 2: The Power BI application using the same filters as in Figure 1, but focusing only on milestones 2700–20 of the Nihaya. Notice that some milestones have more than one alignment with al-Tabari’s Taʾrikh. This might indicate that al-Nuwayri has amalgamated material from two different parts of al-Tabari’s text.

The application effectively allows one to explore the ‘DNA’ of one book and to see how it is made up of reused segments of other, earlier books.4 The app can also be used to explore questions of dissemination by investigating how parts of a work are reused in the centuries after the author’s death. The team members are now collectively experimenting with a series of apps with different books on the x-axis on the basis of this al-Nuwayri prototype, and we hope to iteratively develop a template app that can then be adapted by researchers to address their own research questions.

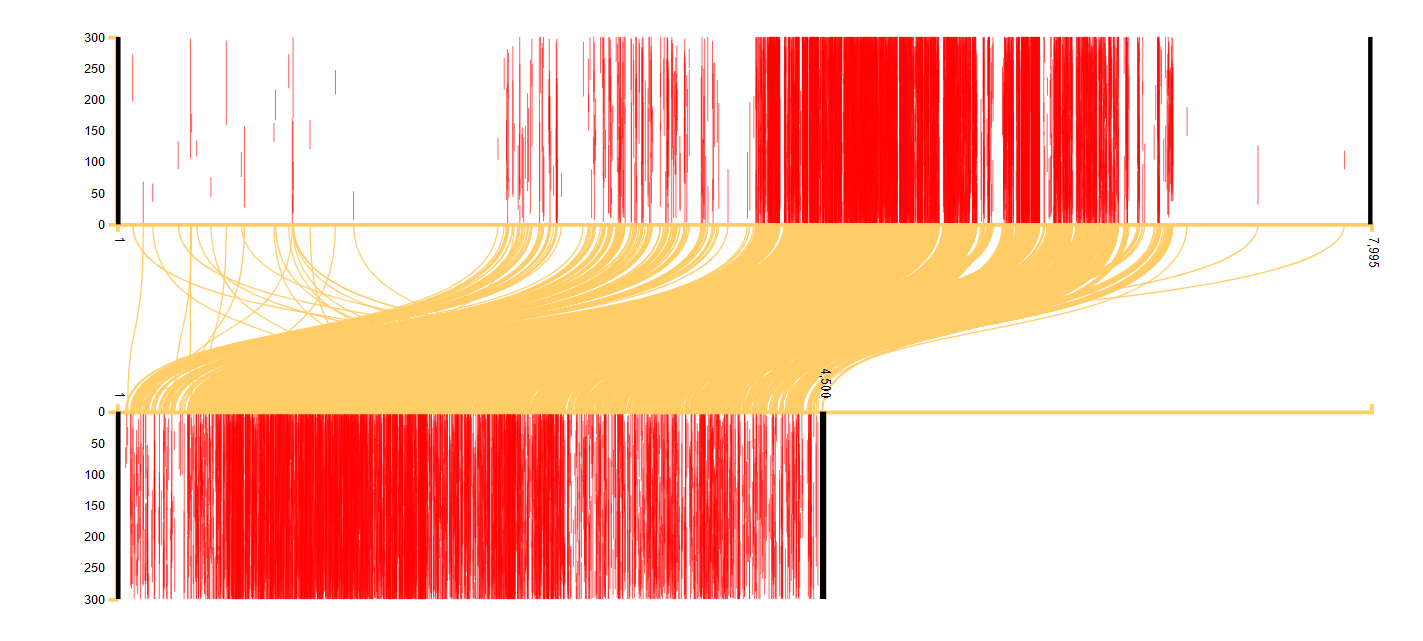

The application described above is great for investigating how one book is constructed or disseminated. It does not, however, provide any information about how the reusers of a text are themselves organising the reused text. At present we use a book-to-book visualisation that shows the reuse of milestones between a book pair, as shown in Figure 3 (this visualisation can be seen in many KITAB blog posts).

Figure 3: Al-Nuwayri’s Nihaya (on the top) compared with Ibn al-Athir’s Kamil (on the bottom) in the KITAB pairwise visualisation. Notice how this visualisation, unlike the Power BI app, allows us to compare the locations of reused milestones in the two texts.

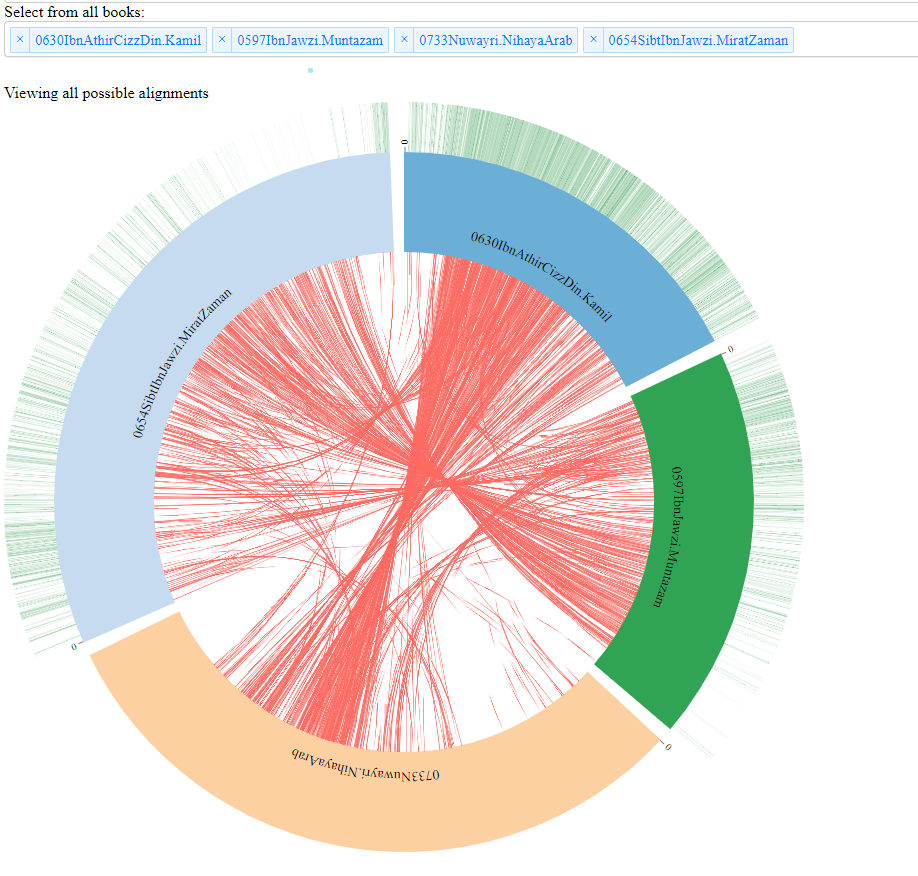

It would be immensely powerful to be able to take a similar approach to relationships among multiple books. Fortunately, researchers in genetics have already developed a solution for visualising these kinds of alignments (in the field, this kind of comparative practice is called synteny). As noted above, biologists are interested in tracing alignments of sequences between chromosomes and species. One popular approach is to use a circular representation (sometimes called Circos5), a donut-shaped visualisation in which the outer ring is broken into segments representing individual chromosomes or genomes and lines (chords) are drawn between segments of the outer ring to represent alignments. If one replaces the chromosome alignment data with book alignments, the result is a visualisation of multiple books that takes account of the location of reuse in all of the compared texts. An example is given in Figures 4 and 5, created using the bioinformatics visualisation library Dash Bio in Python.6

Figure 4: A Dash Bio Circos diagram showing text reuse between al-Nuwayri’s Nihaya and three chronicles (Ibn al-Jawzi’s Muntazam, Ibn al-Athir’s Kamil and Sibt Ibn al-Jawzi’s Mirʾat al-zaman). On each segment of the ring, 0 represents the start of the work, that is, word 0. Chords represent reuse (using the aggregated data set) between all of the chosen texts, with line thickness corresponding to the size of the reuse instance. The green bars on the outside show the parts of the compared texts that are reusing al-Nuwayri’s Nihaya (the user’s chosen primary text). One can clearly see that all of the text is reused in more or less the same order – that is, following a chronological schema.

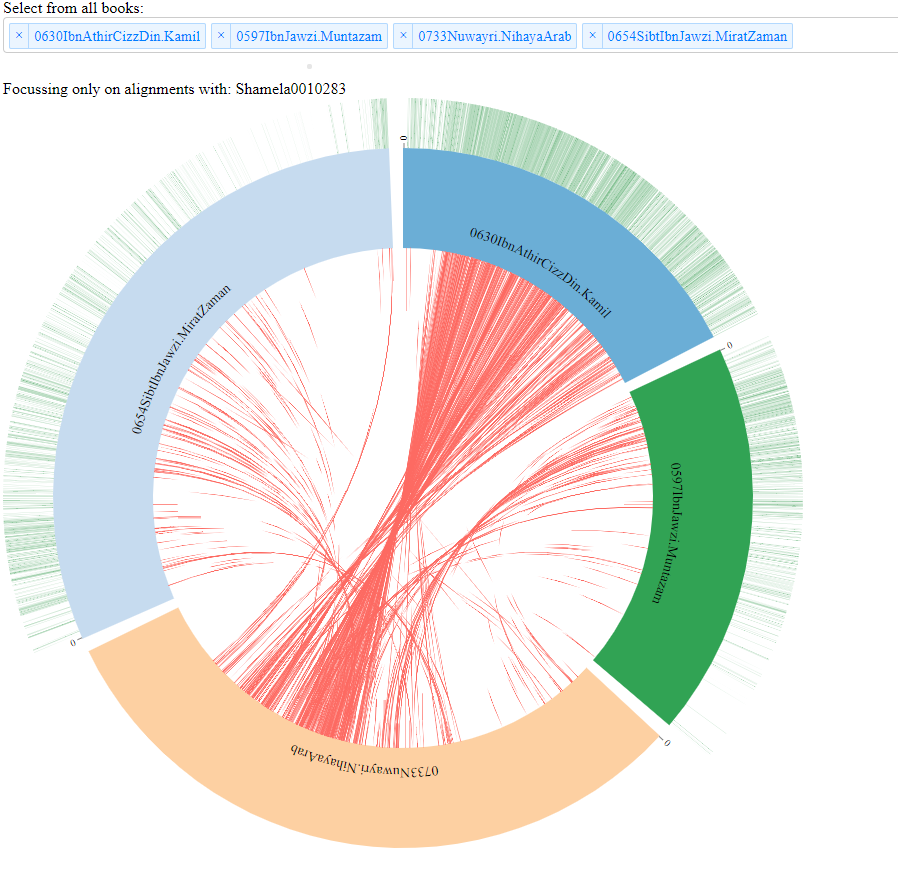

Because of the quantity of reuse between the texts (in particular, the large amount of text shared between Ibn al-Jawzi and Sibt Ibn al-Jawzi), the exact relationships of the three chronicles with al-Nuwayri’s Nihaya are difficult to distinguish in Figure 4. For this reason, we have added the ability to show only chords between the primary text and the other selected texts.

Figure 5: A Circos visualisation comparing the same selection of books as in Figure 4 but displaying chords only for reuse between al-Nuwayri’s Nihaya (the user’s chosen primary text) and the other selected texts. In this case, one can more easily see that the Nihaya shares text most heavily with the Kamil.

This circular representation of the data allows for significant customisation. One can colour individual chords to represent different types of data. It is also possible to add other data ‘tracks’ to the visualisation to show different types – bars on the outside of the circle or line graphs on the inside. We will be experimenting with different approaches and hope to share more soon. For the moment, I hope I have shown the importance of thinking across fields and learning from other approaches. Such an approach will help us avoid reinventing the wheel (or, in this case, circos).

-

For a good explanation, see David A. Smith, Ryan Cordell and Abigail Mullen, ‘Computational Methods for Uncovering Reprinted Texts in Antebellum Newspapers’, American Literary History 27/3 (2015), https://viraltexts.org/2015/05/22/computational-methods-for-uncovering-reprinted-texts-in-antebellum-newspapers/. This paper references Dan Gusfield, Algorithms on Strings, Trees, and Sequences: Computer Science and Computational Biology (Cambridge, 1997), which helpfully compares alignment in genomics with other ‘string’ problems in computer science (for the non-computer scientist, the latter is particularly dense and perhaps not that helpful). ↩

-

For a more in-depth explanation and diagram, see https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Genetic-Code. ↩

-

For a helpful guide to tools for visualising genomics, see Cydney B. Nielsen, Michael Cantor, Inna Dubchak, David Gordon and Ting Wang, ‘Visualizing Genomes: Techniques and Challenges’, Nature Methods Supplement 7/3 (2010), esp. 7–9. A trawl of the literature indicates that the available tools do not seem to have changed significantly since the date of this publication. See also Pal Subhajit, Sudip Mondal, Gourab Das, Sunirmal Khatua and Zhumur Ghosh, ‘Big Data in Biology: The Hope and Present-Day Challenges in It’, Gene Reports 21 (2020). ↩

-

The comparison to DNA is not mine, but Sarah Savant’s. ↩

-

Named after a popular variant; see Circos.ca. Perhaps the most powerful variant of this visualisation is MizBee, but this application cannot presently be easily adapted for non-genomic applications. See http://www.cs.utah.edu/~miriah/mizbee/Overview.html ↩

-

For more information on the functions and code, see https://dash.plotly.com/dash-bio/circos. When the application has been finalised, we will publish our customised version of the code on GitHub. ↩