We continue our investigation of Ibn ʿAsākir’s citations to address our third question about his working methods. When author names appear within his isnāds, what do the names signify for Ibn ʿAsākir? What can isnāds reveal about his reliance on books? Ibn ʿAsākir employs no special transmission terms to refer to material from authored books that his direct informants passed on to him. But can we nonetheless glean information about his use of books from his isnāds?

What is in a name?

We start with author names in isnāds, and the argument —sometimes explicit but more often assumed – that when Ibn ʿAsākir mentions an author’s name within an isnād, he is signalling his reliance on a work written by that author. This claim has been made explicitly by Jens Scheiner, who has described Ibn ʿAsākir’s ‘virtual library’ on the basis of the references to authors found in the TMD. According to Scheiner’s analysis of transmission chains, Ibn ʿAsākir prefaced almost every report

with a single isnād or the riwāya of the work from which he had extracted it. Hence, he was not just faithful to the content of the sources he quoted, but was also very thorough in documenting his information consistently.1

Scheiner concludes that the chains of transmitters in the TMD ‘as a rule of thumb have to be understood as riwāyas of works’.2 Building on the earlier work of Aḥmad M. Nūr Sayf, Gerhard Conrad, ʿUmar al-ʿAmrawī and ʿAlī Shīrī, Steven C. Judd, and Ṭalāl b. Saʿūd al-Daʿjānī (who was far more ambitious than Scheiner was in his search for book sources for the TMD), Scheiner offers in the appendix to his chapter a list of 100 works that Ibn ʿAsākir consulted.3 For fifty-eight of these, he provides one or two riwāyas, chains of transmission documenting recensions of a text.4 He maintains that Ibn ʿAsākir’s use of these and other works illustrates ‘Ibn ʿAsākir’s love for books’.

In Scheiner’s reading, then, the chains of names in the TMD that feature names of people who are known to have written books mean that Ibn ʿAsākir consulted specific books or notebooks written by those author as transmitted to him through the lines of named transmitters. Scheiner reads the TMD and its isnāds metonymically, so that some names represent books, as sometimes is indeed the case in Arabic (and in any language). In ordinary speech, when someone says that the author of a famous work ‘says’ something, it is safe to assume that the speaker is quoting one of the author’s works. Likewise, when the Arabic term qāla precedes an author’s name, it might well mean that the speaker made the statement in a book attributed to him.

However, we should not take this view for granted, and we should be especially mindful of the tendency of print to create a false sense of how fixed a premodern work was – and the same applies even to more recent works. For example, Shakespeare’s works have been heavily scrutinised in efforts to understand his authorial voice, and many debates are still ongoing. We must thus ask: How likely it is that the broad audience with whom Ibn ʿAsākir communicated through the TMD would have routinely understood a name to stand in for a written work, especially since many members of his audience presumably lacked the wide-ranging access to literature that Ibn ʿAsākir himself might have enjoyed, and he largely refrains from referring to his sources explicitly as ‘published’ books?

Reading the TMD and its isnāds with this question in mind is a formidable task. The first step is determining which names in the isnāds in fact belong to authors. Ibn ʿAsākir almost never identifies the people he cites in isnāds specifically as authors. So we had to develop our own way of identifying authors. We sought to capture the broadest picture possible so as to determine the extent to which our data set could be used to reconstruct Ibn ʿAsākir’s ‘library’. We realise that more potential author names could be added to our list, but we do not believe that such additions would change the picture that arises from our work thus far and that casts significant doubt on the validity of efforts to reconstruct a library on the basis of citations in the TMD’s isnāds.

We began by compiling a list of the 238 persons identified by Scheiner, Mourad and al-Daʿjānī as authors whose works Ibn ʿAsākir consulted for the TMD.5 For these 238 individuals, we found 614 surface forms of names, for which we searched in the 77,231 isnāds in our data set.

Our search revealed that Ibn ʿAsākir mentions 149 of these authors in the TMD’s isnāds and that 41% of the isnāds in the TMD (that is, 31,532 isnāds) feature one of these authors.6 Some of these 149 authors are cited more often than others: fifty authors appear in 38% of all isnāds. The rest of the authors are cited much less frequently. The proportion of isnāds that mention an author would probably be higher if additional authors and surface forms were to be included in the list.

| Author | Died | Times cited | Cumulative percentage of isnāds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Muhammad al-Akfani | 524/1129 | 3,394 | 4.4 |

| al-Bayhaqi | 458/1066 | 3,026 | 8.3 |

| al-Khatib | 463/1071 | 2,977 | 12.2 |

| Abu Nu'aym | 430/1038 | 1,851 | 14.6 |

| Ibn Sa'd | 230/845 | 1,613 | 16.7 |

| Abu Bakr b. Abi Dunya | 281/894 | 1,261 | 18.3 |

| Abu Ya'la | 307/919 | 997 | 19.6 |

| Khalifa | 241/855 | 924 | 20.8 |

| Abu Muhammad b. Abi Nasr | 420/1029 | 848 | 21.9 |

| Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi | 428/1036 | 834 | 23 |

| Abu 'Abd Allah al-Balkhi | ? | 762 | 23.9 |

| Ibn Manda | 395/1005 | 746 | 24.9 |

| al-Zubayr b. Bakkar | 256/870 | 691 | 25.8 |

| al-Daraqutni | 385/995 | 648 | 26.6 |

| Ibn Makula | 485/1092 | 564 | 27.4 |

| al-Kilabi | 396/1005 | 532 | 28.1 |

| Abu Bishr al-Dulabi | 310/923 | 495 | 28.7 |

| Ya'qub b. Sufyan | 277/890 | 486 | 29.3 |

| al-Harith b. Abi Usama | ? | 485 | 30 |

| Ibn Abi Khaythama | 279/892 | 450 | 30.5 |

| Ibn Abi Shayba | ? | 426 | 31.1 |

| Muslim | 261/875 | 385 | 31.6 |

| Yahya b. Muhammad b. Sa'id | ? | 365 | 32.1 |

| al-Baghawi | 317/929 | 328 | 32.5 |

| Muhammad b. Harun | ? | 290 | 32.9 |

| Ibn al-Mubarak | 181/797 | 283 | 33.2 |

| al-Tabarani | 360/971 | 279 | 33.6 |

| Muhammad b. Muhammad | ? | 266 | 33.9 |

| al-'Uqayli | 322/934 | 250 | 34.3 |

| al-Asma'i | ? | 237 | 34.6 |

| Ibn Ma'in | 233/847 | 209 | 34.8 |

| 'Abd Allah b. Ahmad | ? | 206 | 35.1 |

| Yunus b. Bukayr | 199/815 | 178 | 35.3 |

| Sayf | 180/796 | 167 | 35.5 |

| Muhammad b. Jarir | 310/923 | 166 | 35.8 |

| al-Zuhri | ? | 158 | 36 |

| Abu Zur'a | 264/878 | 156 | 36.2 |

| 'Abd al-Razzaq | 211/827 | 154 | 36.4 |

| al-Khara'iti | 327/939 | 151 | 36.6 |

| Waki' | ? | 150 | 36.8 |

| Abu al-Ghana'im | ? | 144 | 36.9 |

| Abu 'Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami | 412/1021 | 136 | 37.1 |

| Ibn Ishaq | 151/767 | 135 | 37.3 |

| Hisham b. 'Ammar | ? | 133 | 37.5 |

| 'Abd al-Ghafir | 529/1134 | 126 | 37.6 |

| Abu Bakr al-Jawzaqi | ? | 116 | 37.8 |

| al-Humaydi | 488/1095 | 116 | 37.9 |

| al-Bukhari | 256/870 | 115 | 38.1 |

| Ibn Yunus | 347/958 | 101 | 38.2 |

| al-Qati'i | ? | 95 | 38.3 |

Table 5.1: The fifty authors whom Ibn ʿAsākir cites most frequently in the TMD’s isnāds. The death dates come mostly from Scheiner and Mourad.

We counted the number of isnāds in which each author name appears and calculated the percentage of all isnāds represented by author-containing chains.

The chronological distance separating the cited authors from Ibn ʿAsākir varies, but many of the authors he cites most often lived relatively close to his own lifetime. These authors include Abu Muhammad al-Akfani, al-Bayhaqi, al-Khatib, Ibn Manda and Abu Nuʿaym, all of whom were two or at most three generations from Ibn ʿAsākir and who all pursued projects that involved bringing material of different kinds together.

Scheiner, Mourad and al-Daʿjānī classify these people as authors, but did their writings truly constitute books that Ibn ʿAsākir consulted? There are some problems with this conception.

Problem 1: Who is the author of any given report?

An isnād in the TMD names many people but does not specify which of them should be reckoned the author of the report to which the isnād is attached. A particular piece of information might pass through several compilations before arriving in the TMD. So who gets authorial credit?

Consider the case of Abu Muḥammad al-Akfani (d. 524/1129), Ibn ʿAsākir’s fourth-ranked direct informant overall. Scheiner considers him an author, ascribing three ‘unknown biographical works’ to him: Tasmiyat man ḥaddatha Dārayyā, Tasmiyat quḍāt Dimashq and Tasmiyat wulāt Dimashq. In general, Scheiner classifies works bearing the title Tasmiya (‘list’ or ‘enumeration’) alongside other author-composed works in his library listings.7 This reasoning makes Abu Muḥammad al-Akfani an author, and as Table 5.1 shows, he is the author Ibn ʿAsākir cites most often.

But Abu Muhammad al-Akfani also transmitted material from other authors, as both Scheiner and Mourad note.8 The following isnād illustrates his role:

أخبرنا أبو محمد بن الأكفاني أنبأنا عبد العزيز الكتاني أنبأنا أبو محمد بن أبي نصر أنبأنا أبو الميمون بن راشد أنبانا أبو زرعة حدثني الحكم بن نافع أنبأنا شعيب

Abū Muḥammad b. al-Akfānī [Abu Muhammad al-Akfani] informed us that Abū Muḥammad b. Abī Naṣr [Abu Muhammad b. Abi Nasr] communicated to them from Abū al-Mamūn b. Rāshid from Abū Zurʿa [Abu Zur'a] from al-Ḥakim b. Nāfiʿ from Shuʿayb …

Here Ibn ʿAsākir cites not just one author (Abu Muhammad al-Akfani) but three, including Abu Muhammad b. Abi Nasr (d. 420/1029) and Abu Zur'a (d. 264/878).

Indeed, Abu Muhammad al-Akfani transmits from several earlier authors, listed in Table 5.2.

| Author | Died | Times cited by Abu Muhammad al-Akfani |

|---|---|---|

| Abu Muhammad b. Abi Nasr | 420/1029 | 1,609 |

| Abu Zur'a | 264/878 | 577 |

| al-Khatib | 463/1071 | 309 |

| Ibn Muhanna | 365/975 | 22 |

| al-Kilabi | 396/1005 | 18 |

| Abu Bakr b. Abi Dunya | 281/894 | 15 |

| Ahmad b. al-Ma'ali | ? | 9 |

| Muhammad b. Muhammad | ? | 7 |

Table 5.2: Other authors cited by Abu Muhammad al-Akfani in the TMD.

How are we meant to know when Abu Muhammad al-Akfani is passing on material from his own compilation in which he quotes earlier works and when he is transmitting the work of an earlier author, such as Abu Muhammad b. Abi Nasr? The language of the isnāds almost never gives such information.

Problem 2: Numerous chains go back to the same author

The list of riwāyas given by Scheiner suggests a tidy set of citations of books. But our data set yields a much more complex picture.

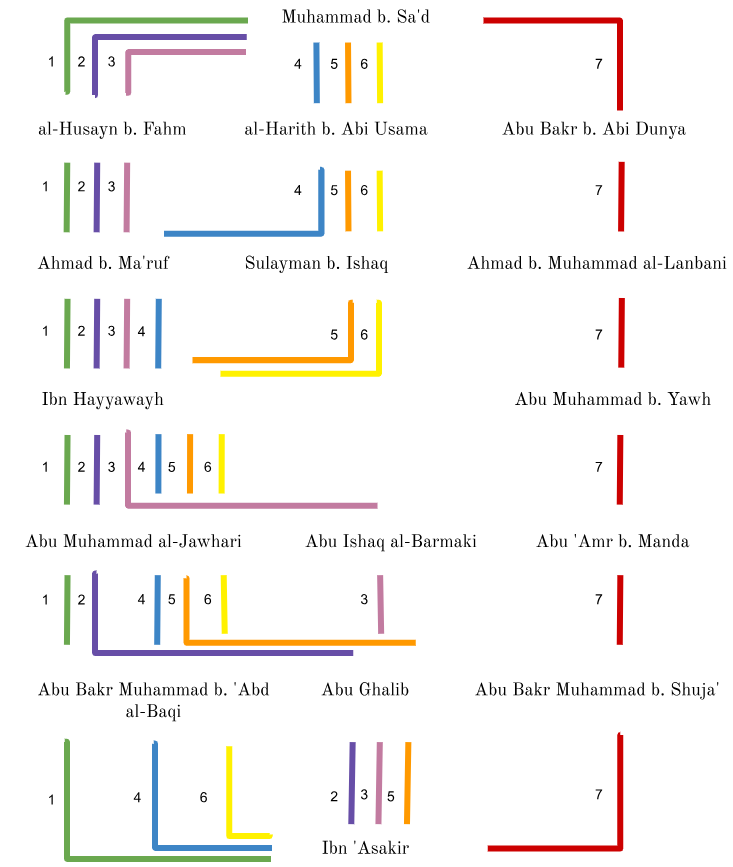

In 2020, when studying the role of Muḥammad b. Saʿd [Ibn Sa'd] (d. 230/845) in providing information to Ibn ʿAsākir, we mapped the primary routes through which Ibn ʿAsākir derived information from Ibn Saʿd (see Figure 5.1). The resulting diagram looked like a map of the London Underground.

Figure 5.1: The main routes through which Ibn ʿAsākir says he received information from Ibn Sa'd. Seven generations separate him from Ibn Sa'd. Graph by Masoumeh Seydi.

We noted in a blog post:9

The isnads were not sitting there ready to be plucked from the TMD; instead, they required many hours of painstaking disambiguation of names and pruning of data. We leave much on the cutting-room floor, and the left side of the graph does not yield a simple picture of transmission. This messiness points to the vagaries of naming practices and the deterioration of information through the transmission process. But it also suggests that the way in which Ibn ʿAsakir accessed the wisdom of earlier centuries was likely quite complex. Different parts of Ibn Saʿd’s oeuvre may have passed through different lines. Alternatively, the transmission may have been more mediated than that, with Ibn ʿAsakir accessing a more dispersed corpus of Ibn Saʿd materials.

We pointed out that the questions we raised about the transmission of Ibn Sa'd’s works had broad relevance for understanding how Ibn ʿAsākir obtained material from written works in general. We also observed that a critical step would be further work on named entity recognition.

We now have the general data to make this point even more strongly. When we look at Ibn ʿAsākir’s citations of all authors in the TMD, not just Ibn Sa'd, we find a dense tangle of transmission lines. The London Underground metaphor doesn’t do it justice.

We investigated this tangle in three ways.

First, we tried to count unique isnāds going back to authors. This yielded very high numbers – sometimes more than a hundred isnāds leading to a single author– because the multiple surface forms of names inflated the counts. Nevertheless, it is clear that Scheiner’s list underestimates the scope of the phenomenon.

Second, we counted the number of direct informants who passed on isnāds citing authors. As with the first count, we found the numbers significantly higher than suggested by Scheiner’s list; Ibn ʿAsākir received authorial material from many direct informants.

| Author | Died | Position in isnād | # of direct informants citing him | Names of direct informants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Muhammad al-Akfani | 524/1129 | 0 | 1 | Abu Muhammad al-Akfani |

| al-Bayhaqi | 458/1066 | 1 | 15 | Abu 'Abd Allah, Abu Muhammad 'Abd al-Jabbar, Abu Nasr 'Abd al-Rahim, Abu al-Hasan 'Ubayd Allah b. Muhammad, Abu al-Muzaffar, Abu Nasr b. al-Qushayri, Abu Nasr al-Qushayri, Abu al-Ma'ali, Abu al-Qasim al-Mustamli, Abu al-Qasim, Abu al-Ma'ali Muhammad b. Isma'il, Abu Muhammad Hibat Allah b. Sahl, Abu al-Qasim b. Abi 'Abd al-Rahman, Abu 'Abd Allah al-Furawi, 'Abd Allah Muhammad b. al-Fadl |

| al-Khatib | 463/1071 | 1 | 40 | Abu Mansur al-Shaybani, Abu Mansur Muhammad b. 'Abd al-Malik, Abu Mansur b. Khayrun, Abu al-Wahsh, Abu al-Fada'il al-Hasan b. al-Hasan, Abu al-Hasan al-Ghasani, Abu al-Najm, Abu Bakr b. al-Mazrufi, Abu Turab, Abu al-Ma'ali al-Husayn b. Hamza, Abu al-Hasan, Abu Muhammad, Abu Bakr Muhammad b. 'Abd al-Baqi, Abu Muhammad Tahir b. Sahl, Abu al-Husayn b. Kamil, Abu Muhammad b. Sabir, Abu al-Qasim al-Samarqandi, Fatima bt. al-Husayn, Abu 'Abd Allah Muhammad b. 'Ali, Abu al-Hasan b. Sa'id, Abu Ja'far Muhammad b. Abi 'Ali, Abu al-Qasim al-'Alawi, Abu Mansur b. Zariq, Abu al-Sa'ud Ahmad b. 'Ali b. Muhammad, Ibn Sa'id, Abu Ja'far Muhammad b. Abi al-Hamadhani, Abu al-Husayn b. Qubays, Abu al-Hasan Barakat b. 'Abd al-'Aziz, Abu al-Qasim, Abu al-Hasan 'Ali b. Barakat, Abu al-Sa'adat, al-Khatib, Abu al-Faraj Ghayth, Abu al-Hasan b. Qubays, Abu al-Hasan 'Ali b. Ahmad, Abu al-Qasim al-Wasiti, Abu Turab Haydara, Abu Muhammad al-Sulami, 'Ali b. al-Hasan, Abu al-Hasan 'Ali b. Ahmad al-Faqih |

| Ibn Sa'd | 230/845 | 5 | 8 | Abu Talib, Abu Ghalib, Abu Bakr Muhammad b. Shuja', Abu Muhammad b. 'Abd al-Baqi, Abu Bakr al-Shahid, Abu Nasr, Abu Bakr Muhammad b. 'Abd al-Baqi, Abu Bakr |

| Abu Bakr b. Abi Dunya | 281/894 | 4 | 11 | Muhammad b. Tawus, Abu al-Qasim al-Samarqandi, Abu Ya'qub Yusuf b. Ayyub, Abu Muhammad b. Tawus, Abu Sa'd Ahmad b Muhammad b. al-Baghdadi, Abu Bakr Muhammad b. Shuja', Abu al-Qasim, Abu al-Qasim al-Mustamli, Abu Sa'd b. al-Baghdadi, Abu Bakr, Abu al-Qasim al-'Alawi |

| Abu Nu'aym | 430/1038 | 1 | 21 | Abu Sa'd Muhammad b. Muhammad, Abu al-Hasda al-Faradi, Abu al-Qasim al-Samarqandi, Abu Sa'd Muhammad b. Muhammad b. Muhammad, Abu Nu'aym, Abu 'Ali, Abu al-Qasim Ghanim, Abu Talib Muhammad b. Mahfouz, Abu 'Ali al-Muqri', Abu 'Ali al-Haddad, Abu Sa'd Mutriz, Abu 'Ali al-Husayn b. Ahmad, Abu al-Qasim, Abu al-Qasim b. al-Husayn, Abu al-Ma'ali 'Abd Allah b. Ahmad, Abu al-Qasim Mahmud b. Ahmad, Abu al-Muzaffar, Abu al-Barakat, Abu Muhammad al-Sulami, Abu 'Ali al-Hasan b. Ahmad, Abu Sa'd al-Mutriz |

| Abu Ya'la | 307/919 | 3 | 14 | Umm al-Mujtaba, Abu al-Qasim Tamim b. Abi Sa'id, Abu al-Qasim al-Samarqandi, Abu al-Muzaffar, Abu 'Abd Allah al-Khallal, Abu al-Qasim al-Mustamli, Abu Sahl Sa'duwayh, Abu al-Mujtaba al-'Alawiyya, Umm al-Baha', Abu 'Abd Allah al-Husayn b. 'Abd al-Malik, Abu Sahl b. Sa'duwayh, Abu al-Husayn b. al-Farra', Abu Mansur al-Husayn b. Talha, Abu 'Abd Allah al-Furawi |

| Khalifa | 241/855 | 5 | 4 | Abu Ghalib, Abu al-Barakat, Abu al-'Izz Thabit b. Mansur, Abu Ghalib al-Mawardi |

Table 5.3: The eight authors cited most frequently by Ibn ʿAsākir.

We included in our count all author-citing direct informants who appear at least five times in Ibn ʿAsākir’s isnāds. The numbers of direct informants would probably be somewhat lower if we were to do further normalisation of names and thus reduce replication; but it would likely be higher if we were to count isnāds featuring authors regardless of the position in which the authors appear, instead of limiting our count to those isnāds in which each author appears in the position most typical for him.10 In any case, it is obvious that Ibn ʿAsākir did not obtain authorial material from just a few direct informants.

It is noteworthy that Ibn ʿAsākir appears to have received material from al-Bayhaqi, al-Khatib and Abu Nu'aym via a large number of direct informants, whereas he relies on far fewer informants for material from authors who died earlier. A likely explanation lies in the reputation and standing of the former set of authors in Ibn ʿAsākir’s day, but a more practical factor is also likely to have been at play: a relatively recent author would have left behind many students whom Ibn ʿAsākir could still meet in person. By contrast, it may have been harder to find authoritative transmitters for authors more remote in time, though thanks to the capacity of isnāds to branch and multiply over time, the opposite outcome was also possible.

Finally, we assessed the frequency of author citations by starting with Ibn ʿAsākir’s top direct informants and counting how often authors appeared in the isnāds for the material they passed on to Ibn ʿAsākir.11 Were any of the direct informants specialists in material from authors?

| Direct informant | # of authors cited per Scheiner | Names of authors cited per Scheiner | # of isnāds with author names | Percentage of all his isnāds | # of authors cited in data set | Names of authors cited in data set |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Muhammad al-Akfani | 3 | Abu al-Zur'a, Ibn Muhanna, Musa b. 'Uqba | 3,380 | 100% | 1 | Abu Muhammad al-Akfani |

| Abu al-Qasim al-Samarqandi | 8 | Ya'qub b. Sufyan, Ibn 'Adi, Ibn Ishaq, Ibn Sallam, Musa b. 'Uqba, Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi, Sayf, al-Shirazi | 2,831 | 32% | 74 | Abd Allah b. Ahmad, Abd Allah b. Wahb, Abd al-Rahman b. Ibrahim al-Dimashqi, Abd al-Razzaq, Abu 'Abd Allah Muhammad b. Ahmad b. Muhammad, Abu 'Abd Allah al-Balkhi, Abu 'Aruba al-Harrani, Abu 'Awwana, Abu 'Ubayd al-Qasim b. Sallam, Abu Bakr b. Abi Dawud, Abu Bakr b. Abi Dunya, Abu Bakr b. Ziyad, Abu Bishr al-Dulabi, Abu Dawud, Abu Hudhayfa, Abu Ishaq al-Fazari, Abu Khaythama, Abu Muhammad al-Akfani, Abu Muhammad b. Abi Nasr, Abu Nu'aym, Abu Ya'la, Abu Zur'a, Abu al-Aswad, Abu al-Hasan 'Ali b. Muhammad b. Ahmad, Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi, Ahmad b. Hanbal, Hisham b. 'Ammar, Ibn 'Adi, Ibn Abi Dawud, Ibn Abi Shayba, Ibn Ishaq, Ibn Ma'in, Ibn Makula, Ibn Mujahid, Ibn Sa'd, Ibn Sallam, Ibn al-Mubarak, Ibn al-Munadi, Ishaq b. Bishr al-Bukhari, Khalifa, Muhammad b. Harun, Muhammad b. Jarir, Muhammad b. Muhammad, Musa b. 'Uqba, Muslim, Sayf, Sufyan b. 'Uyayna, Surayj b. Yunus, Waki', Ya'qub b. Sufyan, Yahya b. Muhammad b. Sa'id, Yunus b. Bukayr, al-Asma'i, al-Baghawi, al-Bayhaqi, al-Bukhari, al-Daraqutni, al-Faryabi, al-Harith b. Abi Usama, al-Hasan b. Sufyan, al-Humaydi, al-Khara`iti, al-Khatib, al-Kilabi, al-Mada`ini, al-Nasa'i, al-Qati'i, al-Shafi'i, al-Shirazi, al-Suli, al-Tabarani, al-Walid b. Muslim, al-Zubayr b. Bakkar, al-Zuhri |

| Abu Ghalib | 4 | Ibn Abi Khaythama, Ibn Sa'd, Khalifa, al-Zubayr b. Bakkar | 2,635 | 54% | 46 | Abd Allah b. Ahmad, Abd al-Razzaq, Abu 'Abd Allah al-Balkhi, Abu 'Aruba al-Harrani, Abu Bakr b. Abi Dawud, Abu Bakr b. Abi Dunya, Abu Dawud, Abu Muhammad b. Abi Nasr, Abu Nu'aym, Abu al-Ghana`im, Abu al-Hasan b. Sumay', Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi, Hisham b. 'Ammar, Ibn Abi Dawud, Ibn Abi Khaythama, Ibn Abi Shayba, Ibn Ishaq, Ibn Jusa, Ibn Ma'in, Ibn Makula, Ibn Sa'd, Ibn Sallam, Ibn al-Kalbi, Ibn al-Mubarak, Khalifa, Muhammad b. Jarir, Muhammad b. Muhammad, Sufyan b. 'Uyayna, Surayj b. Yunus, Waki', Yahya b. Muhammad b. Sa'id, al-Baghawi, al-Daraqutni, al-Faryabi, al-Harith b. Abi Usama, al-Humaydi, al-Khatib, al-Khutabi, al-Kilabi, al-Mada`ini, al-Qati'i, al-Suli, al-Tusi, al-Walid b. Muslim, al-Zubayr b. Bakkar, al-Zuhri |

| Abu al-Qasim al-Mustamli | 0 | - | 1,747 | 65% | 38 | Abd al-Rahman b. Ibrahim al-Dimashqi, Abd al-Razzaq, Abu 'Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami, Abu 'Aruba al-Harrani, Abu 'Awwana, Abu Bakr al-Jawzaqi, Abu Bakr b. Abi Dawud, Abu Bakr b. Abi Dunya, Abu Dawud, Abu Hudhayfa, Abu Nu'aym, Abu Ya'la, Hisham b. 'Ammar, Ibn Abi Dawud, Ibn Hibban, Ibn Ishaq, Ibn Ma'in, Ibn al-A'rabi, Ibn al-Mubarak, Muhammad b. Jarir, Muhammad b. Muhammad, Musa b. 'Uqba, Muslim, Sufyan b. 'Uyayna, Waki', Yahya b. Muhammad b. Sa'id, Yazid b. Muhammad b. Iyas, Yunus b. Bukayr, al-Baghawi, al-Bayhaqi, al-Hakim, al-Harith b. Abi Usama, al-Hasan b. Sufyan, al-Khatib, al-Suli, al-Walid b. Muslim, al-Waqidi, al-Zuhri |

| Abu 'Ali al-Haddad | 1 | Abu Nu'aym | 1,570 | 81% | 17 | Abu 'Aruba al-Harrani, Abu Bakr Ahmad b. al-Fadl, Abu Muhammad al-Akfani, Abu Nu'aym, Abu Ya'la, Abu Zur'a, Ahmad b. Sayyar, Hisham b. 'Ammar, Ibn Ishaq, Ibn Ma'in, Ibn Manda, Ibn Sa'd, Muhammad b. Ishaq al-Sarraj, al-Hasan b. Sufyan, al-Khatib, al-Tabarani, al-Walid b. Muslim |

| Abu 'Abd Allah | 2 | Ibn Abi Khaythama, al-Zubayr b. Bakkar | 1,557 | 55% | 33 | Abd al-Razzaq, Abu 'Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami, Abu 'Aruba al-Harrani, Abu 'Awwana, Abu Bakr al-Jawzaqi, Abu Khaythama, Abu Muhammad b. Abi Nasr, Abu Nu'aym, Abu Ya'la, Abu al-Aswad, Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi, Ibn Abi Khaythama, Ibn Jusa, Ibn Ma'in, Ibn Manda, Ibn Sallam, Ibn al-Mubarak, Ibrahim al-Harbi, Muhammad b. Jarir, Muhammad b. Muhammad, Yahya b. Muhammad b. Sa'id, al-Baghawi, al-Bayhaqi, al-Bukhari, al-Daraqutni, al-Harith b. Abi Usama, al-Khatib, al-Kilabi, al-Mada`ini, al-Tusi, al-Walid b. Muslim, al-Zubayr b. Bakkar, al-Zuhri |

| Abu Muhammad al-Sulami | 2 | al-Hasan b. Muhammad al-'Amili, Ibn Makula | 1,466 | 45% | 36 | Abd al-Razzaq, Abu 'Aruba al-Harrani, Abu 'Ubayd al-Qasim b. Sallam, Abu Hudhayfa, Abu Muhammad al-Akfani, Abu Muhammad b. Abi Nasr, Abu Nu'aym, Abu Zur'a, Ahmad b. al-Ma'ali, Al-Haytham b. 'Adi, Hisham b. 'Ammar, Ibn Abi Khaythama, Ibn Ma'in, Ibn Makula, Ibn Manda, Ibn Sa'd, Ibn al-A'rabi, Ibn al-Mubarak, Muhammad b. 'A'idh, Muhammad b. Harun, Muhammad b. Jarir, Muhammad b. Muhammad, Waki', Ya'qub b. Sufyan, al-Baghawi, al-Bukhari, al-Daraqutni, al-Kalbi, al-Khara`iti, al-Khatib, al-Kilabi, al-Mada`ini, al-Tahawi, al-Walid b. Muslim, al-Waqidi, al-Zuhri |

| Abu Bakr Muhammad b. 'Abd al-Baqi | 1 | al-Waqidi | 1,292 | 68% | 20 | Abu 'Abd Allah al-Balkhi, Abu 'Aruba al-Harrani, Abu 'Awwana, Abu Nu'aym, Abu Ya'la, Ahmad b. Hanbal, Ibn Abi Dawud, Ibn Abi Shayba, Ibn Sa'd, Ibn al-Mubarak, Muhammad b. Muhammad, Yahya b. Muhammad b. Sa'id, al-Baghawi, al-Daraqutni, al-Faryabi, al-Harith b. Abi Usama, al-Khatib, al-Walid b. Muslim, al-Waqidi, al-Zubayr b. Bakkar |

Table 5.4: The eight direct informants whose isnāds mention authors most frequently.

Table 5.4 focuses on eight direct informants whose isnāds feature the highest number of authors. The second and third columns provide the number and names of authors cited by each informant according to Scheiner, whereas the fifth and sixth columns give the same information as found in our data set. It is evident that the data set yields far more author citations than Scheiner’s lists do.12 As noted previously, our data model counts Abu Muhammad al-Akfani as an author and as a direct informant.

Some of these people might have specialised in authorial material. A likely example is Abu 'Ali al-Haddad, of whose isnāds 81% mention the names of authors. When we look at the isnāds of the fifty direct informants who cite the most authors, we find that in thirty-three cases half or more of their isnāds contain author names. It is worth noting that these direct informants’ transmission lines nearly always name more authors than mentioned by Scheiner.

If it is true that the chains of transmitters in the TMD ‘as a rule of thumb have to be understood as riwāyas of works’, Ibn ʿAsākir’s library would have been much larger than projected by Scheiner. But we do not believe that the neat image of books on shelves accurately reflects the way in which Ibn ʿAsākir accumulated and managed his material. Ibn ʿAsākir does not cite such a library of books in the TMD. This is not to say he had no books to hand; but it is generally not possible to say on the basis of his isnāds which books or, more likely, which parts of which books he used for particular parts of the TMD.

Problem 3: Ibn ʿAsākir does not cite authors’ works directly

Ibn ʿAsākir received material from authors such as al-Bayhaqi and al-Khatib via numerous informants. But he often did not cite these authors’ books directly. An interesting case is that of al-Khatib and his book Tārīkh Baghdād, which Ibn ʿAsākir mentions at least sixteen times but does not in fact cite his book. He almost certainly had access to a version of the book, but when he wanted to quote al-Khatib, it seems that he used quotations from it taken down from various of his direct informants. He thus preferred to quote these authoritative people over a book. Curiously, Scheiner says he could not find any riwāya for the Tārīkh Baghdād in the TMD (‘no riwāya mentioned or found’).13

Ibn ʿAsākir mentions on several occasions that he had looked up information on particular figures in the Tārīkh Baghdād but failed to find the people in question. For example, Ibn ʿAsākir reports that one Idrīs b. Ibrāhīm compiled (ṣannafa) a book (kitāb) called Uns al-jalīs wa-masarrat al-anīs (‘Intimacy with companions and joy with close friends’) containing reports about a number of people (Ibn ʿAsākir provides a list). But, he says, he does not have any information on who might have passed on reports from Idrīs b. Ibrāhīm (man rawā ʿanhu), and he notes that Abū Bakr al-Khaṭīb (that is, al-Khatib) does not mention Idrīs in his Tārīkh Baghdād.14 This and similar cases present Ibn ʿAsākir as a careful researcher who sought information from written sources and admitted to failure when he found none.

By contrast, Ibn ʿAsākir mentions al-Khatib as a transmitter in 2,977 isnāds that support reports on Damascus and its illustrious community, but without reference to the Tārīkh Baghdād itself. He relies on as many as forty direct informants for these quotations, as noted above in Table 5.3 (though these numbers are tentative, as more work needs to be done on the Name List, and the isnāds cannot be extracted directly from the TMD).15 The direct informants to whom Ibn ʿAsākir attributes most of the isnāds featuring al-Khatib are listed in Table 5.5. The table also shows how often he cites each informant and thus what proportion of the material passed to Ibn ʿAsākir by that informant the reports citing al-Khatib represent.

| Direct informant | Citations of al-Khatib | Total citations | Percentage of al-Khatib citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Muhammad al-Sulami | 741 | 3,224 | 23% |

| Abu al-Qasim al-Wasiti | 550 | 575 | 96% |

| Abu Muhammad al-Akfani | 260 | 3,380 | 8% |

| Abu al-Qasim al-'Alawi | 255 | 2,069 | 12% |

| Abu Mansur b. Khayrun | 165 | 371 | 44% |

| Abu al-Najm | 105 | 153 | 69% |

| Abu Muhammad Tahir b. Sahl | 90 | 178 | 51% |

Table 5.5: The eight direct informants who cite al-Khatib most often.

In sum, then, when Ibn ʿAsākir quotes reports from al-Khatib, he mentions the latter personally. By contrast, he refers to the Tārīkh Baghdād only in connection with information that it does not contain. This raises a possibility. Did Ibn ʿAsākir seek out people (his direct informants) to back up specific quotations that he had read first in the Tārīkh Baghdād? Perhaps he had a sort of shopping list of passages from al-Khatib’s book and sought out informants who could corroborate them. It was only when he failed to find the material he expected in the Tārīkh (and thus also could not back it up with an informant) that he felt compelled to mention the book itself. The high degree of textual overlap between the TMD and the Tārīkh Baghdād could point to just this kind of dependency – to Ibn ʿAsākir’s combing the pages of al-Khatib’s book for the required information.16

For most of the direct informants listed in Table 5.5, citations of al-Khatib represent only a fraction of the content they shared with Ibn ʿAsākir. Al-Khatib’s work was not their main line of business. In one interesting case, Ibn ʿAsākir mentions, in an entry for a direct informant named Abu Turab, that he obtained a volume of al-Khatib’s Tārīkh Baghdād from Abu Turab; but when Ibn ʿAsākir quotes al-Khatib via Abu Turab, most often alongside other direct informants, he does not mention the Tārīkh Baghdād.17 In another case, he notes that Abū al-Ḥasan b. Abī al-ʿAttār [Abu al-Hasan al-'Attar] passed on texts from al-Khatib, including ‘a piece of the Tārīkh Baghdād as well as Ibn Qutayba’s Adab al-kātib and Mushkil al-Qurʾān, and [other] volumes in circulation’.18 In fact, of the informants in Table 5.5, only Abu al-Qasim al-Wasiti appears to have specialised in transmitting material from al-Khatib.

When Ibn ʿAsākir writes about these direct informants in his Muʿjam shuyūkh and the TMD, he does not give any particular prominence to their role in transmitting quotations from al-Khatib. He does not, for example, mention al-Khatib at all in his Muʿjam al-shuyūkh entry for Abu Muhammad al-Sulami, who ranks first among his direct informants in terms of the frequency with which al-Khatib’s name appears in his isnāds.19 Nor does he highlight al-Khatib when writing about Abu Muhammad al-Akfani. The mustadrak, the text appended to the TMD by the work’s modern editors, contains an entry for Abu Muhammad al-Akfani, which quotes Ibn ʿAsākir as follows:

He began learning by audition when he was a boy of nine. After that, [he audited] from his father and from Abū al-Qāsim al-Ḥannāʾī, Abū al-Ḥusayn Muḥammad b. Makkī, ʿAbd al-Dāʾim b. al-Ḥasan al-Hilālī, Abū Bakr al-Khaṭīb [al-Khatib], ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Kattānī, Abū Naṣr b. Ṭulāb, Abū al-Ḥasan b. Abī al-Ḥadīd, Ṭāhir b. Aḥmad al-Qāʾinī, the preacher ʿAbd al-Jabbār b. Burza, Abū al-Qāsim b. Abī al-ʿAlāʾ and many other people.20

The works attributed to the authors listed in this entry are often long. Al-Khatib’s Taʿrīkh Baghdād, for example, runs to more than 1.8 million words in the OpenITI version of the text.21 Did Abu Muhammad al-Akfani listen to the entirety of each of these authors’ works? Maybe, but it seems highly unlikely, and is made even more improbable by the fact that many may still have been works in progress at the time. Most importantly, nothing of the sort is in fact claimed about him.

What is likely true for Abu Muhammad al-Akfani is at least equally likely true for Ibn ʿAsākir. If his direct informant had only partial access to a work through audition, his own access was probably limited to whatever portion his informant had been able to obtain.

There is also the possibility that the mention of al-Khatib in isnāds points to other works of his. Al-Dhahabī’s biography of Ibn ʿAsākir states that Ibn ʿAsākir received material through audition from Abū al-Qāsim al-Nasīb [Abu al-Qasim al-'Alawi] and that he obtained twenty volumes of al-Khatib’s writing from him in this manner.22 These twenty volumes seem to refer not to the Tārīkh Baghdād but to another work, called Fawāʾid al-nasīb, which consists of Hadiths that al-Khatib selected for Abu al-Qasim al-'Alawi. One of these volumes (volume 13) appears to have made its way into the OpenITI corpus.23 As noted in Post 3, Ibn ʿAsākir was about 9 years old when Abu al-Qasim al-'Alawi died, suggesting that the passing of material to him occurred with assistance.

Let us return to Scheiner’s argument that Ibn ʿAsākir’s author-citing isnāds should be taken to constitute riwāyas for these authors’ works. However, in spite of the number of isnāds featuring al-Khatib in the TMD, Scheiner concludes that the TMD contains no riwāyas for three works by al-Khatib, including the Tārīkh Baghdād. We would argue that this is because the reading of all isnāds as riwāyas is in fact untenable, and Scheiner perhaps understands this is the case. Otherwise, he would have had to give dozens of riwāyas for this work – versus the reasonably small number he lists for other books. Above all, we contend that it is important to listen to what Ibn ʿAsākir says he is doing. He is not claiming that he got his information from al-Khatib’s books; rather, he is quoting al-Khatib himself within the chain of authorities.

Problem 4: Ibn ʿAsākir only rarely cites titles within isnāds

The fact that Ibn ʿAsākir does not cite al-Khatib’s books in his isnāds is not unusual.

We searched all of the isnāds in our data set for the titles of works identified by al-Daʿjānī, Scheiner and Mourad. Our search encompassed 456 unique titles including generic title words such as tārīkh, sīra, futūḥ, maghāzī, ṭabaqāt, musnad, sunan, nasab and tafsīr. In addition to searching for tārīkh on its own we also looked for thirty-five titles with the word tārīkh, including Tārīkh Samarqand and Tārīkh al-umam wa-l-mulūk. Fifteen searched titles began with the word tasmiya (e.g. Tasmiyat mawālī ahl Miṣr).24

We found and verified 165 references to book titles across the set of about 77,231 isnāds, which means that 0.2% of all isnāds mention a title. Eighty-one of the isnāds contained the word tārīkh. In seven cases the term appeared as a descriptor for a person, such as someone cited as the author (ṣāḥib) of a work on history. Fifteen of the isnāds contained the word tasmiya. The other terms yielded much fewer results. Sīra, maghāzī, sunan and nasab appeared once each, while futūḥ appeared twice, tafsīr three times, and ṭabaqāt and musnad five times each.

| Title | Author | # of mentions |

|---|---|---|

| Tadhyīl Tārīkh Nayṣābūr | Abd al-Ghafir | 19 |

| Tārīkh al-Andalus | al-Humaydi | 18 |

| Tārīkh Jurjān | Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi | 16 |

| Maʿrifat al-ṣahāba | Abu Nu'aym | 8 |

| Maʿrifat al-ṣahāba | Ibn Manda | 7 |

| Tārīkh Ṣūfiyya | Abu 'Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami | 4 |

Table 5.6: Book titles cited by Ibn ʿAsākir in isnāds, with their authors.

The search also turned up works that we had not searched for. For example, Ibn ʿAsākir mentions a Tasmiyat umarāʾ yawm al-jamal and attributes the work to ‘Yaʿqūb’, with the following isnād

وأخبرنا أبو القاسم بن السمرقندي أنا أبو بكر بن الطبري أنبأنا ابوالحسين ببن الفضل أنبأنا عبد الله بن جعفر نبأنا يعقوب قال في تسمية أمراء يوم الجمل قال وعلى خيل الأزد

Abu al-Qasim al-Samarqandi informed us that Abū Bakr b. al-Ṭabarī transmitted from Abū al-Ḥusayn b. [sic] al-Faḍl, who communicated from ʿAbd Allāh b. Jaʿfar, who communicated from Yaʿqūb, who said in the Tasmiyat umarāʾ yawm al-jamal …

This was not one of the fifteen tasmiya works we searched for with our script.

It is noteworthy that Ibn ʿAsākir’s own TMD bears both tārīkh and tasmiya in its full title, Tārīkh madīnat Dimashq wa-dhikr faḍlihā wa-tasmiyat man ḥallahā min al-amāthil aw ijtāza bi-nawāḥīhā min wāridīhā wa-ahlihā (on the meaning of tasmiya both here and in Ibn ʿAsākir’s citations, see Post 6).

When we do find Ibn ʿAsākir citing titles, they seem to belong to books that could be easily mined. Perhaps Ibn ʿAsākir asked people he encountered who knew and had access to these books whether the books contained information relating in any way to Damascus. In an era in which people were conduits for books, it is perfectly natural to imagine that he obtained very specific information in this manner. The people he cites were well known in his day for possessing authority to transmit certain parts of certain books. His device for locating information in these works was not a table of contents or an index, but people.

We acknowledge that improving our search scripts might turn up more titles. We intend to publish them after doing some further work so other scholars wanting to look for mentions of particular books can refine them for this purpose. Additional search terms can also be added, and some can be modified to reflect variations in citation conventions. However, we are confident that additional results would not significantly change our conclusion that Ibn ʿAsākir cites book titles only rarely.

As a final point, we note that we also undertook a search for these terms across the text of the TMD, outside of isnāds as well as within them. We then tagged points in the text where book titles and the names of their authors appeared together. This search produced poor initial results, with many false positives. We will be refining the search and expect improvements, but the challenges it poses are a further indicator of the character of the citation patterns we are studying.

Problem 5: Text reuse evidence does not line up with isnāds

Using Power BI software, we built an application that could ingest all of the alignments between the TMD and earlier works contained in the OpenITI corpus.25 The number of potential overlaps was large. We therefore narrowed it down to thirty-nine books mentioned by Scheiner. Table 5.7 lists the works that have the most alignments with the TMD.

| Author | Died | Title of book | # of TMD milestones matched | # of TMD milestones best match | Max. length of alignment (words) | # of isnād citations (all positions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| al-Khatib | 463/1071 | Tārīkh Baghdād | 3,527 | 2,533 | 281 | 2,977 |

| Ibn Sa'd | 230/845 | al-Ṭabaqat al-kubrā | 2,227 | 1,348 | 281 | 1,613 |

| Ahmad b. Hanbal | 241/855 | Musnad | 2,127 | 994 | 271 | 85 |

| al-Tabarani | 360/971 | al-Muʿjam al-kabīr | 1,597 | 679 | 246 | 279 |

| al-Bayhaqi | 458/1066 | al-Sunan al-kubrā | 1,314 | 591 | 245 | 3,026 |

Table 5.7: The five pre–Ibn ʿAsākir OpenITI works with the largest number of alignments with the TMD.

Here is how we built this table and what it shows. There are 27,177 milestones, each comprising 300 word tokens, in the TMD. The text reuse data we have generated with passim is based on a comparison of the Arabic text in each of the TMD milestones with the Arabic text of milestones in the other works. The comparisons are collected in separate files. Power BI software joins the files together within a large data frame on the basis of the TMD milestones. We can manipulate this data to gather statistics on the alignments between the TMD and each of the earlier books or between the TMD and groups of them, and we can examine the aligned text and see its location within each book. We can also create visualisations of the relationship between the TMD and the other books.

We assessed the alignments between the TMD and the earlier books in two ways. First, we counted how many milestones in the TMD align with milestones in the other books. An alignment with a TMD milestone often extends over more than one milestone in the comparison book. This is because we split the books into milestones mechanically, at automatic 300-word intervals, and the divisions thus do not reflect natural divisions, such as sections or paragraphs, within the text itself.

A given passage in the TMD may also match passages in multiple other texts. This happens, for example, when Ibn ʿAsākir draws on a source that relies on a still earlier source or that shares a (sometimes lost) source with other works in the corpus. In order to include only the most salient alignments, we filtered the results to show only the most substantial match for each aligned milestone of the TMD (according to the number of words matched). The filtering inevitably caused the loss of some data. But when there are multiple possible sources for TMD sections, searching for the best match for each TMD milestone can give a good indication of the source Ibn ʿAsākir probably used, since visualisations make it possible to assess consecutive reuse (see Figure 5.2). We have experimented with this method with other authors and their works and have generally found it helpful for drawing such conclusions. Best-milestone matching is especially important when an author has relied on two or more histories that build consecutively on one another – not generally the case for Ibn ʿAsākir but very much the case for an author such as Shihāb al-Dīn al-Nuwayrī (d. 732/1332).26

There is much to be said about our text reuse data and about what can be learned by studying it in Power BI. We will limit ourselves here to highlighting just one point: although we can see many alignments between the TMD and earlier works, these do not map as well as we might expect to mentions of the names of these works’ authors. Ibn ʿAsākir cites authors in contexts that offer no evidence of text reuse, and his reuse of texts is often unaccompanied by citation of the relevant authors.

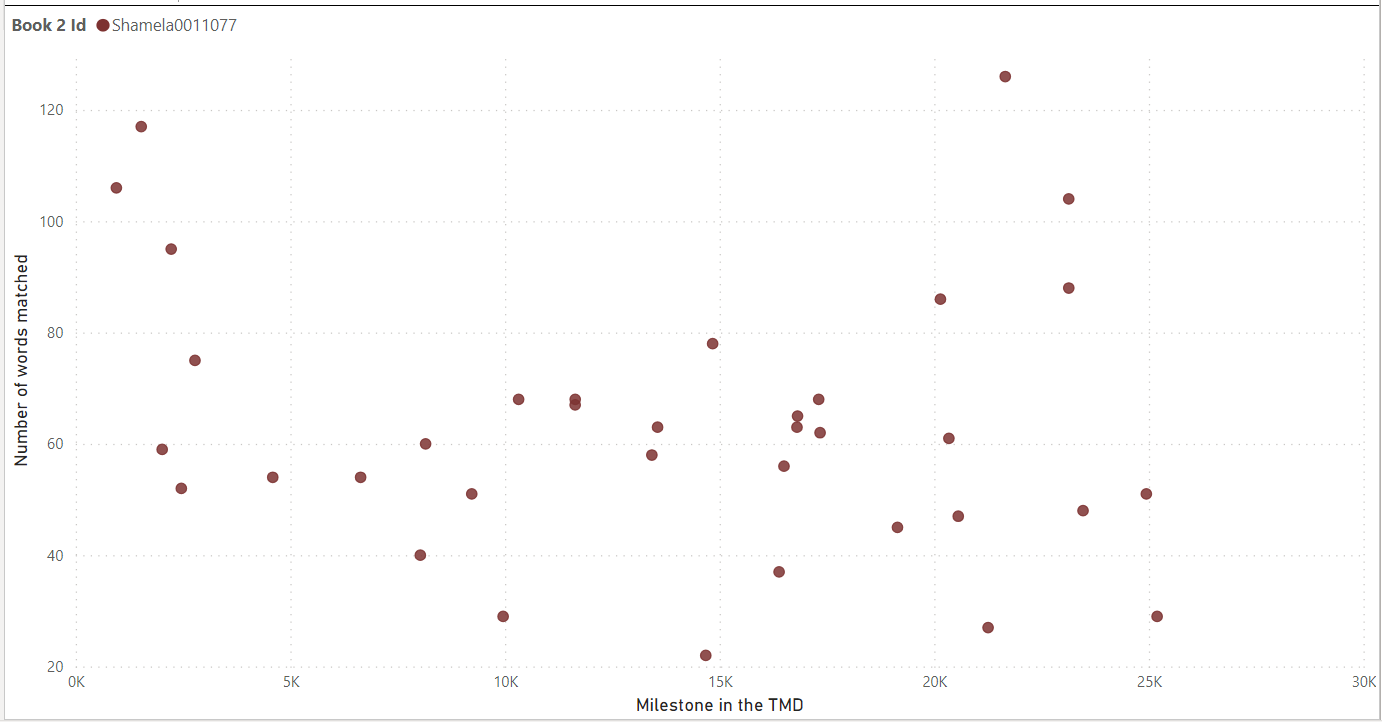

Let’s consider two examples. The first is the case Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi’s Tārīkh Jurjān, listed in Table 5.6 and briefly mentioned in Post 3.27 Passim detected matches with the Tārīkh Jurjān in fifty-four milestones of the TMD, thirty-six of which represent the best match for that milestone of the TMD. These best matches are represented in Figure 5.2.

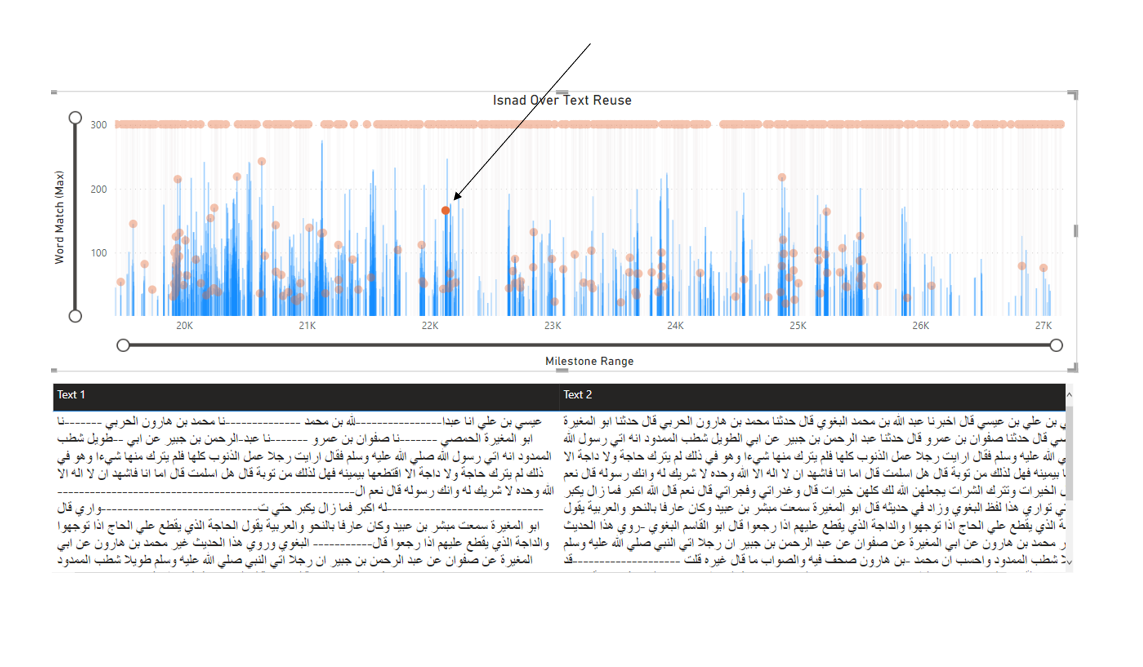

Figure 5.2 Instances of alignment between the TMD’s 300-word milestones and Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi’s Tārīkh Jurjān.

The longest match, shown in Figure 5.3, consists of 126 words.

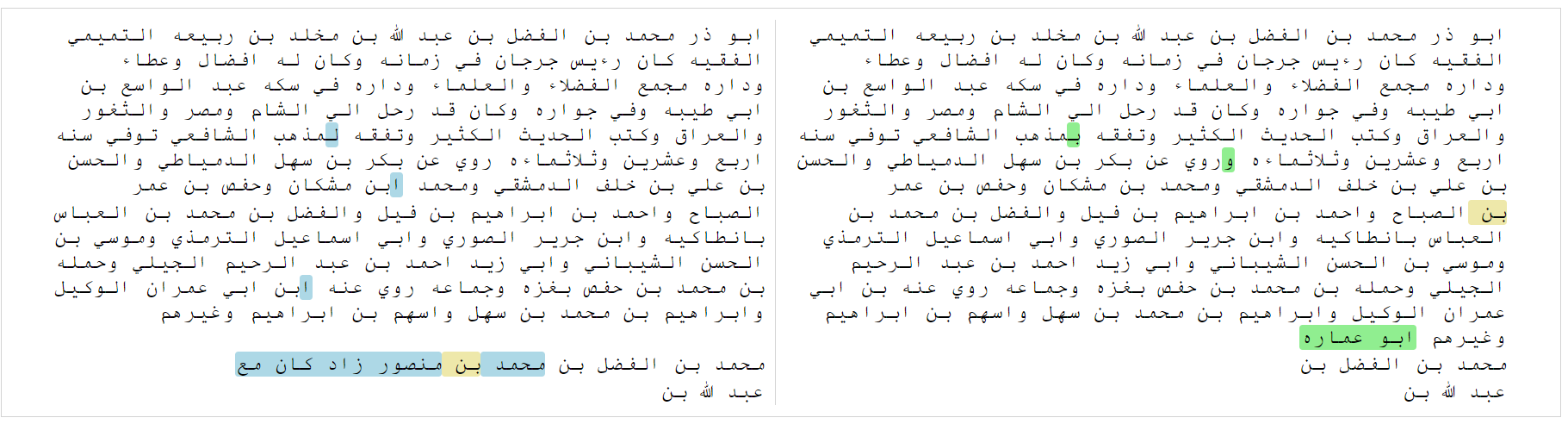

Figure 5.3: The longest alignment between Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi’s Tārīkh Jurjān (on the left) and Ibn ʿAsākir’s TMD (on the right), with the limited divergences between the two texts highlighted.28

Still, we have far more citations of al-Sahmi himself (without mention of his book) than we have evidence of Ibn ʿAsākir’s reuse of al-Sahmi’s book, since Ibn ʿAsākir cites al-Sahmi in 834 isnāds.29

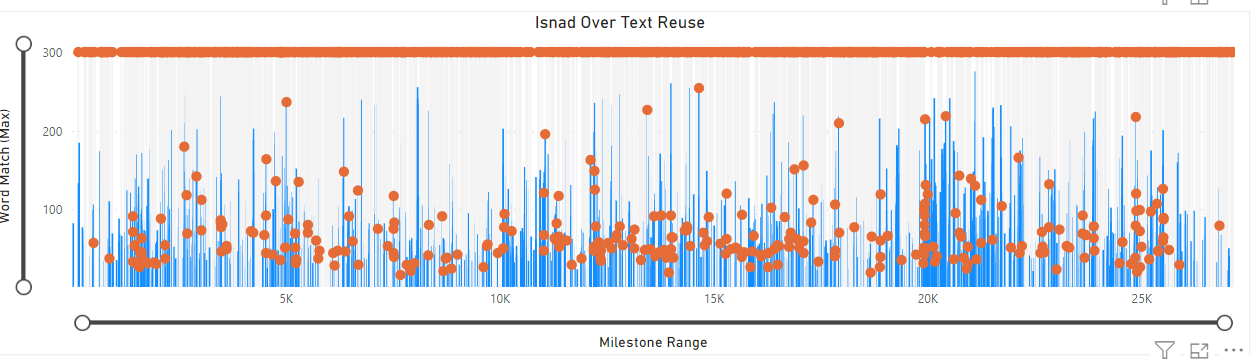

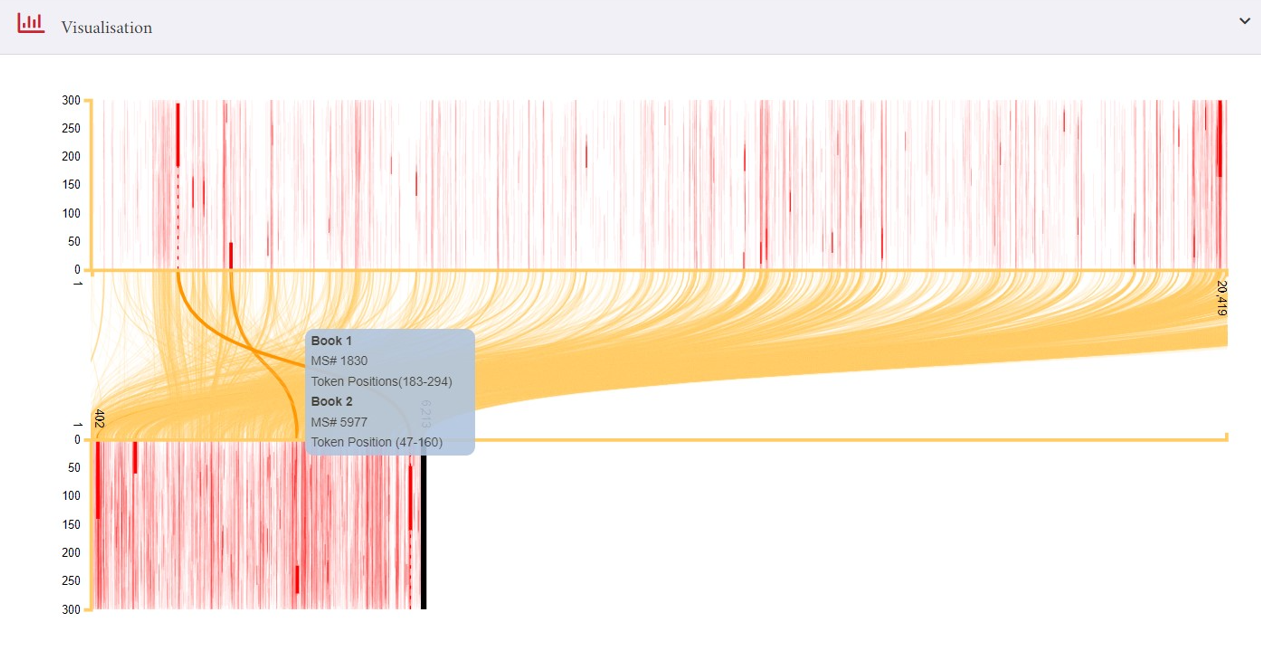

The second example involves al-Khatib and his book Tārīkh Baghdād. Al-Khatib is the author whom Ibn ʿAsākir cites most often, and the Tārīkh Baghdād is the book for whose reuse we have the most evidence. Figure 5.4 shows the relationship between the two books.

Figure 5.4: Alignments between the long TMD (top) and the shorter Tārīkh Baghdāḍ (bottom), with yellow lines connecting matching milestones.30

The relationship is clearer when we zoom in on a part of the graph, as in Figure 5.5.

Figure 5.5: Alignments between a section of the TMD (between milestones 0 and 20,419) and the entirety of the Tārīkh Baghdād, showing that Ibn ʿAsākir drew on all parts of the latter in composing the TMD and that he used material from the Tārīkh Baghdād in all parts of his own work.

Figure 5.5: Alignments between a section of the TMD (between milestones 0 and 20,419) and the entirety of the Tārīkh Baghdād, showing that Ibn ʿAsākir drew on all parts of the latter in composing the TMD and that he used material from the Tārīkh Baghdād in all parts of his own work.

When we compared the TMD milestones that show evidence of reuse of al-Khatib’s book with the milestones in which Ibn ʿAsākir cites al-Khatib himself, we found only partial overlap. Some milestones contain citations but no reuse, whereas others feature reuse but no citation.

In order to represent this information visually, Sohail Merchant used Power BI to produce the graph in Figure 5.6. This graph covers the entire text of the TMD, but it is also possible to zoom in on a particular milestone range. In addition, Power BI can show the text of the two aligned passages for each match, as illustrated in Figure 5.7.

Figure 5.6: Reuse of the Tārīkh Baghdād in the TMD (blue lines) and citations of al-Khatib in the TMD (orange dots). The length of each blue line indicates the length of the alignment between the two texts. For milestones containing a citation but no reuse, the orange dot appears at the top of the graph. In milestones containing both reuse and citation, the placement of the dot on the blue line is arbitrary; the precise location within the milestone was not recorded.

Figure 5.7: A sample alignment between the TMD and the Tārīkh Baghdād (at milestone 22,131 of the TMD).31

These two examples demonstrate that Ibn ʿAsākir sometimes cites authors without reusing their texts and sometimes reuses texts without citing their authors. The evidence thus indicates that Ibn ʿAsākir was not simply copying out works by earlier authors, and his citations of authors by name do not necessarily point to these authors’ books. In both cases, he is citing an author’s name more than we can account for when we look at reuse.

In the case of al-Khatib, it is possible that the orange dots of citation without the blue lines of reuse in Figure 5.6 mark instances in which Ibn ʿAsākir is citing other books by al-Khatib, though without naming them (Scheiner does not list other books by al-Khatib in Ibn ʿAsākir’s ‘library’; al-Daʿjānī does but stresses the primacy of the Tārīkh Baghdād).32 More than twenty other books attributed to al-Khatib in the OpenITI corpus contain alignments with the TMD. Although it is thus likely that Ibn ʿAsākir drew on al-Khatib’s other writings, it is noteworthy that he does not say so. Many of these other works are short (consisting of fewer than 10,000 words) and might represent treatments of topics useful to Ibn ʿAsākir (as he himself created many similar, short works). Further, the possibility that al-Khatib created other works (including lectures students wrote down) that have not come down to us cannot be excluded.33

When we compared reuse and citation for other works supposedly used by Ibn ʿAsākir, we obtained similar results. We created animations that take a viewer through each section of the TMD and that painstakingly illustrate the mismatch between his citations of an author and the evidence of reuse of that author’s works upon which Scheiner says Ibn ʿAsākir relied.34 The animations do not offer high entertainment, but they do make the point that text reuse evidence does not line up with isnāds.

Conclusions

The following points summarise our findings concerning author names in isnāds:

-

About 40% of all isnāds mention an author’s name, and some mention more than one. But it is rare for Ibn ʿAsākir to specify that a person mentioned in an isnād is an author or to give the title of a work. When an isnād contains multiple authors’ names, it is typically unclear to which one (if any) the transmitted information is to be attributed.

-

Ibn ʿAsākir provides many different isnāds for many of the authors he cites. The paths of transmission are rarely simple.

-

Ibn ʿAsākir evidently wished to demonstrate that he obtained information via many different people. He cites al-Khatib, for example, through many direct informants. However, he rarely cites al-Khatib’s Tārīkh Baghdād, even though he indicates that he had the book to hand when he says that he searched for information within it but failed to find it.

-

Ibn ʿAsākir mentions titles of works in only about 0.2% of all his isnāds – in other words, extremely rarely. When he does cite what seem to be titles, these most often to texts contain the words tārīkh or tasmiya. Notably, these words are found in the title of his own book, and their prominence perhaps reflects his perception of ‘proper’ citation and/or the ease with which such works could be mined and their material slotted into the TMD. Still, even relatively frequent mentions of an author’s work (e.g. Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi’s Tārīkh Jurjān, which is cited fifteen times) are eclipsed by the far more frequent mentions of the work’s author (834 times for Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi).

-

The text reuse data indicates that Ibn ʿAsākir drew on the books of many of the authors he cites. But he seems to have done so in mediated ways, since the milestones in which he cites authors generally do not match well the milestones in which he reuses their books. His citations of Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi and al-Khatib are cases in point: he cites them even where he does not reuse their writings and reuses their works even where he does not cite them. He also possibly used other writings by the authors whose names he cites. Assuming that a reference to al-Khatib, for example, necessarily points to the Kitāb Baghdād risks overlooking smaller works by al-Khatib that may have been more useful for Ibn ʿAsākir in composing the TMD. Ibn ʿAsākir himself created many such small works and would have understood their usefulness; in addition, his connections may have given him access to the more rare short works.

These findings have implications for Scheiner’s thesis that isnāds with author names represent, ‘as a rule of thumb’, riwāyas for these authors’ written works, and that these isnāds can thus be used to reconstruct the library that Ibn ʿAsākir had at his disposal. We believe that this interpretation of citation chains is far too optimistic. It overspecifies what Ibn ʿAsākir is saying he is doing. ‘Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi said’ should not be read as ‘Abu al-Qasim al-Sahmi said in the Tārīkh Jurjān’.

On the one hand, Ibn ʿAsākir likely have had access to more written sources than the isnāds would indicate. Remember that Ibn ʿAsākir worked on the TMD over a very long period of time. During this time, he amassed quotations from a variety of sources. It is likely that his work – both the content of the TMD and the way he cited his sources – was guided by the books he had available to him. Furthermore, these books may have directed him to other possible sources of information pertinent to his project. Perhaps he also kept indexed lists of notes.

But on the other hand, he seems to have preferred to access his information, even when it originated in a book, through human intermediaries. This preference is evident in his citations.

However he worked, it is clear that he relied on a corpus of written materials that was more complex than the idea of a library of books would suggest. Our searches touch only the tip of what we believe to be a proverbial iceberg of Ibn ʿAsākir’s use of written materials over his lifetime.

In the next blog post, we continue our exploration of Ibn ʿAsākir’s citations of written materials, this time outside of isnāds.

-

Scheiner, ‘Ibn ʿAsākirʼs Virtual Library’, 247. See also Jens Scheiner, ‘Single Isnāds or Riwāyas? Quoted Books in Ibn ʿAsākir’s Tarjama of Tamīm al-Dārī’, in Maurice A. Pomerantz and Aram Shahin (eds), The Heritage of Arabo-Islamic Learning: Studies Presented to Wadad Kadi (Leiden: Brill, 2016), esp. 51–6 and 67 (based on a small piece of the TMD). ↩

-

Scheiner, ‘Ibn ʿAsākirʼs Virtual Library’, 251. The term riwāya came to mean the ‘transmission of a written text through oral expression’; S. Leder, ‘Riwāya’, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2^nd^ ed., http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0927. As Leder notes, ‘It is this function of riwāya, based on the great value attached to oral testimony, which is hard to understand for outsiders and which is most characteristic of Islamic scholarship.’ ↩

-

For Scheiner’s description of his method, see Scheiner, ‘Ibn ʿAsākirʼs Virtual Library’, 160–2. As Scheiner notes, al-Daʿjānī’s three-volume monograph about Ibn ʿAsākir’s sources lists far more works than does Scheiner’s list: ‘Al-Daʿjānī claims to have checked all isnāds in the TMD, which took him about five years and led to the identification of approximately 1,000 works Ibn ʿAsākir had used pertaining to ḥadīth, history, and theology. … [I]t should serve as the standard reference work to the sources contained in the TMD. However, the current study will elaborate on the work by al-Daʿjānī, who omitted references and did not list all the biographical works Ibn ʿAsākir used.’ ↩

-

Scheiner lists fifty-two books with one riwāya (he notes a bit of name variation), six books with two riwāyas, and one book (a ‘notebook’ by Ibn Isḥāq) with four riwāyas. ↩

-

Scheiner’s list was our starting point. We added to it authors mentioned by Mourad and then incorporated, from the first volume of al-Daʿjānī’s Mawārid, authors of works pertaining to the following three categories (the categories are al-Daʿjānī’s, the translations ours): (1) histories (tawārīkh), prophetic biography (sīra), the expeditions and raids of the Prophet (maghāzī), the expansion of the early Muslim community beyond its borders (futūḥ), biography (tarājim), genealogy (ansāb), historical accounts (akhbār) and historical topography (khiṭaṭ); (2) theology/dogma (uṣūl al-dīn); and (3) Hadith and its sciences (ḥadīth wa-ʿulūmuhu). For more details on the list of authors and titles, see Savant and Seydi, ‘Ibn ʿAsākir and His History of Damascus’, ‘V. 1.0 – Release Notes’. ↩

-

Savant and Seydi, ‘Ibn ʿAsākir and His History of Damascus’, ‘Isnads’, table ‘NameList’; ‘Isnads_with_Authors’, table ‘Author_Title_SearchTerms’. ↩

-

We discuss this term in greater detail in Post 6, but it seems to denote something like collected notes on a topic. Ibn ʿAsākir uses the term hundreds of times, and in all (or nearly all?) cases, the words that follow it suggest collated information on a particular topic. ↩

-

Mourad treats Abu Muhammad al-Akfani as a teacher of earlier works rather than an author in his own right. The works he considers Abu Muhammad to have taught include Talkhīṣ al-mutashābih by al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Kitāb al-Ḍuʿafāʾ by Abū Zurʿa al-Rāzī (d. 264/878, as preserved by Saʿīd b. ʿAmr al-Bardhāʿī, d. 292/905), Kitāb al-Tārīkh and Kitāb al-Ṭabaqāt by Abu Zurʿa al-Dimashqī (d. 282/895), and Kitāb Tārīkh Dārayyā by Ibn Muhanna al-Khawlānī (d. c. 370/980). Mourad also writes that Abu Muhammad al-Akfani granted Ibn ʿAsākir a certificate to transmit the Taʿrīkh Baghdād and that he read with Ibn ʿAsākir the Kitāb al-Maghāzī of Muḥammad b. ʿĀʾidh (d. c. 233/847). Mourad, Ibn ‘Asakir of Damascus, 18–19. ↩

-

https://kitab-project.org/Mapping-Who-s-Who-in-Isnads-First-Steps/. The graph is from Savant, ‘People versus Books’, 293–4 (a reuse of our post). ↩

-

For the table, we counted only those isnāds in which the cited author appears in the position most common for him, thus excluding any isnāds in which he is cited in a different position. Some, though not all, instances in which an author seems to appear in an unusual position reflect incorrect splitting of names within isnāds. See Savant and Seydi, ‘Ibn ʿAsākir and His History of Damascus’, ‘Isnads_with_Authors’, table ‘AuthorIsnads_TheirDO_Stats’. ↩

-

In Post 3, readers can find this information in the informant profiles of the top five direct informants. ↩

-

The sole case of an author citation listed by Scheiner that is not attested in the data set is Abu Muhammad al-Sulami’s citation of the author al-Hasan b. Muhammad al-'Amili. Our work did not turn up any isnāds to al-'Amili through any direct informant. However, it is highly likely that further refinement of the search terms would turn up references to him, too. Scheiner attributes to him an unknown biographical work, Tārīkh fī maʿrifat al-rijāl. When we search the text of the TMD for this title, we find that Ibn ʿAsākir gives al-Hasan b. Muhammad al-'Amili his own biographical entry and mentions the Tārīkh fī maʿrifat al-rijāl there. Scheiner, ‘Ibn ʿAsākir’s Virtual Library’, 279; Ibn ʿAsākir, TMD, 13:357, ms. 04953. ↩

-

Scheiner, ‘Ibn ʿAsākir’s Virtual Library’, 271. ↩

-

Ibn ʿAsākir, TMD, 7:368, ms. 02440. In total, Ibn ʿAsākir says on nine occasions that he failed to find information on a particular individual in the Tārīkh Baghdād. One of the mentions occurs in an entry for ʿAbd al-Karīm b. Muḥammad b. Manṣūr al-Samʿānī [al-Sam'ani, d. 562/1166], who, Ibn ʿAsākir says, composed a dhayl (continuation) of the Tārīkh Baghdād. Ibn ʿAsākir, TMD, 36:447, ms. 13918. ↩

-

Cf. al-Daʿjānī, Mawārid Ibn ʿAsākir, 1:218–19. ↩

-

Our thoughts on the non-citation of the Tārīkh Baghdād benefited from conversations with Lorenz Nigst, in particular. ↩

-

Ibn ʿAsākir, TMD, 15:378, ms. 05714. ↩

-

Ibn ʿAsākir, TMD, 41:330, ms. 15965. ↩

-

Ibn ʿAsākir, Muʿjam al-shuyūkh, 610–11, entry 751, ms. 310–11. ↩

-

Ibn ʿAsākir, TMD, 73:357, ms. 27980. ↩

-

Abū Bakr Aḥmad b. ʿAlī Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Tārīkh Madīnat al-Salām wa-akhbār muḥaddithīhā wa-dhikr quṭṭānihā al-ʿulamāʾ min ghayr ahlihā wa-wāridīhā, ed. Bashshār ʿAwwād Maʿrūf, 16 vols (Beirut: Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī, 2002), 0463KhatibBaghdadi.TarikhBaghdad.Shamela0000736. ↩

-

Al-Dhahabī, Siyar aʿlām al-nubalāʾ, 20:555, ms. 6647. The expression samiʿnāhā bi-l-ittiṣāl here is of interest. ↩

-

I thank Lorenz Nigst for working out the significance of this passage from al-Dhahabī. See ʿAlī b. al-Ḥasan Ibn ʿAsākir, al-Fawāʾid al-muntakhaba al-ṣiḥāḥ wa-l-gharāʾib (n.p.: Maktabat Aḥmad al-Khadarī, 2014), 0508NasibAbuQasim.Fawaid.ShamAY0032970. See also al-Daʿjānī, Mawārid Ibn ʿAsākir, 3:2159. ↩

-

We also searched the isnāds that contained title words for author names. But the author names we found were often not connected with the titles mentioned in these isnāds. For example, the title of a work might be found deep in the isnād (three or four generations before Ibn ʿAsākir), but an author’s name appears only in the generation prior to Ibn ʿAsākir. We considered the names turned up by this search but did not rely on its results. ↩

-

The work on the application was started by Sarah Savant and Sohail Merchant for the work of Shihāb al-Dīn al-Nuwayrī, and it is now being continued by Merchant and Mathew Barber. The application has proven one of the best tools for collating and interpreting alignments for a single work (whether for investigating possible source texts or for tracing a text’s later reproduction). The passim data set is based on the 2022.1.6 OpenITI corpus release. The Power BI alignments have been filtered to show only those with at least a fifty-word match or at least 90% precision in the match over the entire aligned span. ↩

-

We have fruitfully tested the method on al-Nuwayrī’s Nihāyat al-arab fī funūn al-adab (partially translated by Elias Muhanna as The Ultimate Ambition in the Arts of Erudition). ↩

-

Scheiner, ‘Ibn ʿAsākir’s Virtual Library’, 274; Mourad, Ibn ‘Asakir of Damascus, 22; al-Daʿjānī, Mawārid Ibn ʿAsākir, 1:211–12. ↩

-

Abū al-Qāsim Ḥamza b. Yūsuf al-Sahmī, Tārīkh Jurjān, ed. Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Muʿīd Khān (Beirut: ʿĀlam al-Kutub, 1407/1987), 417–18, 0427Sahmi.TarikhJurjan.Shamela0011077, ms. 255; Ibn ʿAsākir, TMD, ms. 21654. Alignment from passim run on OpenITI release of 2022.1.6. ↩

-

Savant and Seydi, ‘Ibn ʿAsākir and His History of Damascus’, ‘Isnads_with_Authors’, table ‘TransmissionChains_Authors’. ↩

-

Book alignment file from passim run associated with OpenITI release of 2022.1.6. ↩

-

Ibn ʿAsākir, TMD, 56:209, ms. 22131. ↩

-

Al-Daʿjānī, Mawārid Ibn ʿAsākir, 1:217–20. ↩

-

The alignments between the TMD and al-Khatib’s other books do not explain the citation pattern (the reuse occurs entirely between the first 500 or so milestones of the TMD and these works). ↩

-

See the KITAB_CDH YouTube channel. ↩