One of the major challenges for those working with historical Arabic texts lies in names, and in the variety of ways that authors might refer to the same person. An author might, for example, refer to someone as ‘Hisham’, or as ‘the father of ʿUmar’, or as ‘the son of ʿAbbas’. These names might also be joined up, when an author quotes ‘Hisham, the father of ʿUmar’ or when he writes about ‘the father of ʿUmar, Hisham’.

Identifying the person in question matters for many reasons. To name but a few: We want to make texts in the OpenITI corpus searchable and need to be able to pinpoint persons, whatever variation of the name is used (and also to distinguish between different Hishams). For studying transmission and book history, we also want to know who’s who. Ryan Muther is working on a method that automatically locates isnads within texts. Who are the people mentioned in the isnads? Likewise, we have much data aligning later works with earlier sources. We want to be able to read citations. Who precisely is being cited?

We (Sarah Savant and Masoumeh Seydi) have been working on a way to link people to variant names and chose as a case study the Taʾrikh madinat Dimashq (TMD) by Ibn ʿAsakir (d. 571/1176).1 It is one of the largest works in the OpenITI corpus, containing eighty volumes in the Dar al-Fikr printed edition and more than 8 million words. The first volume treats the history of the city, including its ancient roots and seventh-century conquest; the second volume treats the topography of the city. The remainder of the book comprises biographies of the elites who lived or passed through Damascus prior to Ibn ʿAsakir’s time. According to Muther’s data, 39% of this massive work is made up of isnads, which means more than 3 million words’ worth of isnads. To put it mildly, that is a lot of names, and each is typically written in a variety of ways.

Our text reuse data suggests that Ibn ʿAsakir, in creating his mammoth work, relied heavily on earlier books, including the Kitab al-Tabaqat al-kabir of Ibn Saʿd (d. 235/830). We wanted to see specifically if we could work out the route – or routes – through which Ibn ʿAsakir accessed the Tabaqat. Did he have access to this book through a specific transmission line, as has been recently argued by specialists on Ibn ʿAsakir?2

The method

Using a search based on so-called regular expressions, we collected all transmission chains within the TMD that included Ibn Saʿd.3 We then trimmed the chains to include only the names cited between Ibn Saʿd and Ibn ʿAsakir. Relying on a transmissive term list prepared by Kevin Jaques, plus some editing, we removed non-name material from the isnad data. To deal with the variant ways of referring to the same person, we created an authorities list to map variations. The authorities list standardised variant Arabic-script names in the TMD isnads to single Latin-script versions, as exemplified below:

| Ibn Hayyawayh | أبو عمر بن حيوية |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | أبي عمر بن حيويه |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | أبو عمر ابن حيوية |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | أبو عمر محمد بن العباس بن حيوية |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | أبو عمر محمد ابن العباس |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | أبي عمر محمد بن العباس بن حيوية |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | ابن عباس |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | محمد بن العباس |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | محمد ابن العباس |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | محمد بن العباس بن حيويه الخزاز |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | أبو عمر محمد بن العباس |

| Ibn Hayyawayh | محمد بن العباس لخزاز |

Table 1: Reconciling variations in names within isnads that feature Muhammad b. Saʿd. Abu ʿUmar b. Hayyawayh (d. 373/983–4) is referred to in many different ways, reflecting differences in orthography and the name elements chosen for inclusion (e.g., the presence or absence of a kunya such as ‘father of so-and-so’). The data file from which this list is excerpted contains 427 such equations for names in Ibn Saʿd isnads.

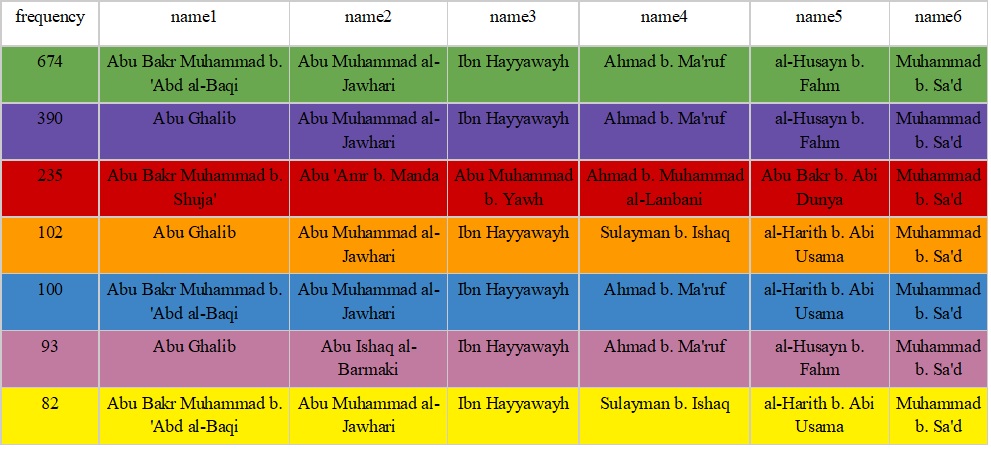

Seydi then used the Levenshtein distance algorithm to group together the most similar chains of names. Even with the reduction of the name variants to single versions, the data remained too extensive for patterns to be visible. So we filtered the total data set to look for only the most commonly occurring transmissive chains, and only those with six nodes, by far the most common length.4

Table 2: The most frequently occurring six-person isnads in the TMD that go back to Muhammad b. Saʿd. Pruning the data to get these transmission chains involved excluding 217 other six-person isnads.

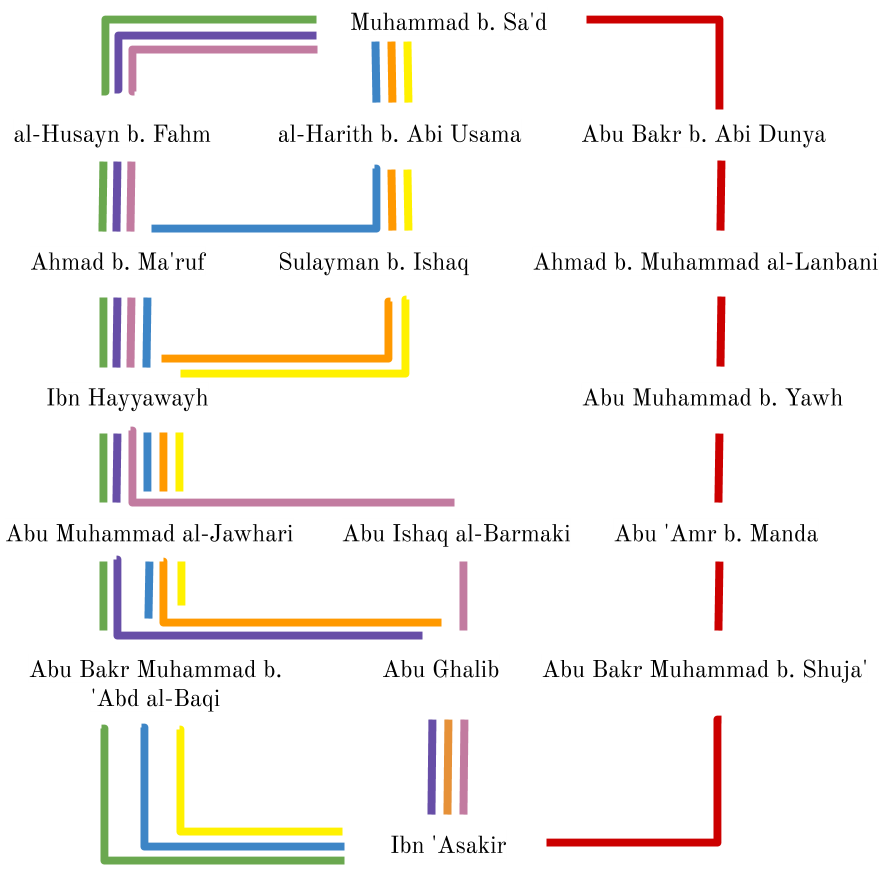

Seydi then graphed the dramatically filtered data, which produced the following graph.

Graph 1: A graphic representation of the subset of lines of transmission from Ibn Saʿd shown in Table 1.

The graph features one coherent chain – in red – that runs back to Ibn Saʿd via Abu Bakr Muhammad b. Shujaʿ (d. 533/1138), Abu ʿAmr b. Manda (d. 475/1082–3), Abu Muhammad b. Yawh (d. unknown), Ahmad b. Muhammad al-Lanbani (d. unknown) and Ibn Abi Dunya (d. 281/894). The other chains, in the left part of the graph, involve nine transmitters in the five generations prior to Ibn Saʿd. The transmissive lines cross one another and look somewhat like a map of the London underground. A key goal in designing the graph was to distinguish the actual transmission lines, in contrast to graphs of isnads that fail to distinguish potential from actual paths. A next step would be weighting the lines to reflect how often the chains they represent occur in our data set.

The effort required to create this data set is important. The isnads were not sitting there ready to be plucked from the TMD; instead, they required many hours of painstaking disambiguation of names and pruning of data. We leave much on the cutting-room floor, and the left side of the graph does not yield a simple picture of transmission. This messiness points to the vagaries of naming practices and the deterioration of information through the transmission process. But it also suggests that the way in which Ibn ʿAsakir accessed the wisdom of earlier centuries was likely quite complex. Different parts of Ibn Saʿd’s oeuvre may have passed through different lines. Alternatively, the transmission may have been more mediated than that, with Ibn ʿAsakir accessing a more dispersed corpus of Ibn Saʿd materials. He may even have been judging the relative merits of different tradents for different pieces of information. It is hard to know whether his audience could track the name variants or the contents that mapped to lines (perhaps not), but the sheer number of them was one of their expectations of a book such as his.5 Giving them what they expected, Ibn ʿAsakir performed his role as a major scholar in the post-canonical era of Hadith transmission.

Just the start

Tracking these persons is just the start of understanding how Ibn ʿAsakir accessed transmissions from Ibn Saʿd. But three points are already evident and indicate towards further areas of exploration.

-

Ibn ʿAsakir cites people for for the information originating with Ibn Saʿd, but he does not generally choose to cite books. The choice to cite people rather than books reflects the knowledge environment in which Ibn ʿAsakir worked. The title al-Tabaqat al-kabir occurs in only two spots in the TMD, once in direct proximity to a transmissive chain. The title al-Tabaqat al-saghir occurs twice, both times outside of an isnad (the relationship between the two Tabaqat works is a subject of some scholarly discussion). The simpler title al-Tabaqat is also attributed to Ibn Saʿd a handful of times (though more often to other authors who wrote such works). This means that in the vast majority of cases in which Ibn ʿAsakir mentions Ibn Saʿd, he does so without direct reference to a work. This matters for understanding both how Ibn ʿAsakir worked and what he wanted his audience to know.

-

The choice to cite people rather than books notwithstanding, the isnads in Table 2 might be helpful for understanding the transmission history of Ibn Saʿd’s book. Scholars today commonly refer to recensions by al-Husayn b. Fahm (d. 289/902), al-Harith b. Abi Usama (d. 282/895) and, possibly, Ibn Abi al-Dunya (though the latter perhaps only for al-Tabaqat al-saghir, as argued by Jens Scheiner).6 The roles of the other tradents in Table 2 and Graph 1 need exploring. In particular, the parts played by Abu Muhammad al-Jawhari (d. 454/1062), Abu Ishaq al-Barmaki (d. 445/1053), Abu Bakr Muhammad b. ʿAbd al-Baqi (d. 535/1140) and Abu Ghalib (d. 527/1132) could be studied by collecting their transmissions from Ibn Saʿd to see whether their contents might represent distinct pieces of the Tabaqat al-kabir. Do citations through a particular chain always come from the same part of Ibn Saʿd’s work? Are Ibn Saʿd citations possibly pulled from the sort of Hadith booklets studied by Konrad Hirschler? As Jaques has argued for Ibn Ishaq’s (d. 151/767) Sira, we should also keep our minds open to the possibility that there was not one al-Tabaqat al-kabir but different versions produced by Ibn Saʿd himself.

-

The citations of Ibn Saʿd within the TMD do not map easily to the reuse alignments we have generated independently with the passim algorithm.7 Why this might be the case is complicated, but the phenomenon seems to arise ultimately (and mostly) from (1) the fact that Ibn ʿAsakir was working with various transmissions from Ibn Saʿd, and these might have been passed on in pieces through written notebooks or collations, as mentioned earlier (meaning that the transmission was highly mediated), and (2) the fact that the alignment data we have is based on a specific edition of Ibn Saʿd’s text held in the OpenITI. In other cases, when an author relied directly on an earlier work, citations map much more easily to text reuse alignments.

These points suggest that we should be exploring the way that Ibn ʿAsakir cites his information more generally (including the role of transmission from people versus books) and the extent to which distinct transmission chains that include authors of well-known and surviving works might have conveyed distinct pieces of their books. Did Ibn ʿAsakir have at hand the books themselves, even if he does not typically cite them directly?

Our lines of enquiry will help us to understand both the reception of Ibn Saʿd’s book and the ways in which authors such as Ibn ʿAsakir went about their work. Before we can get started, though, we need to work on the names that feature in citations, and that is why named entity recognition and the ability to cluster related chains of transmission are so important.

For computer scientists, this sort of work is part of the new stock-in-trade of the Digital Humanities. For historians, it takes time and patience and iteration. Creating lists of name variants is frankly best done with music running in the background and plans for an evening outside. Working on manuscripts, scholars develop skills, including the ability to read and differentiate different scripts. Patience is required. For understanding books in their digital format, named entity recognition might just be a parallel to this sort of work, with rewards aplenty.

-

The OpenITI file that we used for this chapter, 0571IbnCasakir.TarikhDimashq.JK000916-ara1, is based on the eighty-volume 1995–2001 Dar al-Fikr edition edited by ʿUmar al-ʿAmrawi and ʿAli Shiri, but it excludes volumes 71–80. Volumes 71–74 represent a mustadrak, or amendment by the editors (including additional biographical entries); these volumes have now been added to the OpenITI file on the basis of another file in the OpenITI containing the entire Dar al-Fikr work (0571IbnCasakir.TarikhDimashq.Shamela000071-ara1, containing 8.5 million words). Volumes 75–80 represent indices (not added). Gowaart Van Den Bossche and Hamid Reza Hakimi annotated the file for the KITAB project. ↩

-

See e.g. Jens Scheiner, ‘Ibn ʿAsakir’s Virtual Library as Reflected in His TMD’, in Steven Judd and Jens Scheiner, eds, New Perspectives on Ibn ʿAsakir in Islamic Historiography (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 156–257, esp. 179–82. ↩

-

Regular expressions are a formalised way of constructing search patterns, implemented in many computer languages and much text editing software. Regular expressions can be used, for example, to allow for intervening words or to locate passages that cross pages or other boundaries. See Jan Goyvaerts and Steven Levithan, Regular Expressions Cookbook, 2nd. rev. ed. (Farnham: O’Reilly, 2012). ↩

-

There were also isnads with 7–12 transmitters, but six nodes was by far the most common. ↩

-

For reflections on name variation in another context, and the challenges of pinning names to titles, see Konrad Hirschler, A Monument to Medieval Syrian Book Culture: The Library of Ibn ʿAbd al-Hadi (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), 177–8. ↩

-

Scheiner, ‘Ibn ʿAsakir’s Virtual Library’, 181–2 and 269. I use death dates for tradents from Scheiner and from Ahmad Nazir Atassi, ‘The Transmission of Ibn Saʿd’s Biographical Dictionary Kitab al-Tabaqāt al-Kabir’, Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 12 (2017), 56–80. ↩

-

Atassi has noted that ‘expecting a verbatim match between the reports found in a consulted compilation and the corresponding report in the printed [al-Tabaqat al-kabir] is unrealistic’; Atassi, ‘Transmission of Ibn Saʿd’s Biographical Dictionary’, 73. ↩