Introducing passim

The KITAB team’s main digital method is text reuse detection. We typically use ‘text reuse’ to refer to cases in which text is shared verbatim between works, although it could also be applied to looser forms of reuse such as paraphrase. The meaning of text reuse is subject to interpretation, and the concept can be used to investigate a variety of research questions, such as the following:

- How is a commentary upon a work structured, and how far does it rearrange or deviate from the original work?

- Are two or more texts stemmatically related?

- How extensively has a text spread across space and time?

The text reuse algorithm used by KITAB is called passim. The algorithm naively identifies reuse by looking for instances of shared text that meet a certain set of criteria (for example, that the duplicated passages exceed a certain number of words in length and contain fewer than a certain number of intervening words). This means that the text reuse data produced by passim suits certain research questions better than others. If you are interested in cases in which an author mostly paraphrases an earlier work, passim is unlikely to be helpful (or will, at best, provide only a partial picture). Or if you want to explore how certain common phrases are distributed across a large collection of works, passim may need a different set of parameters.

How does passim work?

Put simply, there are two stages to passim’s operation. In the first stage, passim is given a corpus of ‘documents’, relatively short texts. Passim takes each one of these documents and compares it to every other document in the corpus. Whenever passim finds text that is shared between two documents and that meets its criteria (these parameters can be customised to the corpus), it sets those documents aside.

In the second stage, passim compares each document pair using an established alignment algorithm called Smith-Waterman. This algorithm goes through each document character by character and decides whether each character in one document matches a character in the other. Spaces are inserted where characters do not match. The result is an alignment like the one given in the table below.

| Shamela0012129-ara1 | Shamela0023790-ara1 |

| خرج مع ابي بكر الصديق رضي الله عنه في تجارة الي بصري ومعهم نعيمان وكان نعيمان ممن شهد——- بدرا ايضا وك——-ان علي الزاد فقال له سويبط———– اطعمني فقال حتي يجء ابو بكر فقال اما والله لاغيظنك فمروا بقوم فقال لهم سويبط -تشترون مني عبدا قا—لوا نعم فقال انه عبد له كلام وهو قاءل لكم اني حر فان كنتم اذا قال لكم هذه المقالة تركتموه فلا تفسدوا علي عبدي قا-لوا بل نشتريه منك فاشتروه بعشر قلاءص ثم جاءوا فوضعوا في عنقه حبلا ف—————قال نعيمان ان هذا يستهزء بكم واني حر فقالوا قد عرفنا –خبرك وانطلقوا به فلما جاء ابو بكر -اخبروه فاتبعهم ورد عليهم القلاءص واخذه فلما قدموا علي النبي صلي الله عليه وسلم اخبروه فضحك هو واصحابه من ذلك حولا | خرج— ابو بكر——————– في تجارة——— ومعه- نعيمان وسويبط بن حرملة وكانا شهدا بدر—–ا وكان نعيمان علي الزاد فقال له سويبط وكان مزاحا اطعمني فقال حتي يجء ابو بكر فقال اما والله لاغيظنك فمروا بقوم فقال لهم سويبط اتشترون مني عبدا لي قالوا نعم ق-ال انه عبد له كلام وهو قاءل لكم اني حر فان كنتم اذا قال لكم هذه المقالة تركتموه فلا تفسدوا علي عبدي فقالوا بل نشتريه منك——– بعشر قلاءص ثم جاءوا فوضعوا في عنقه حبلا وعمامة واشتروه فقال نعيمان ان هذا يستهزء بكم واني حر قا-لوا قد اخبرنا بخبرك وانطلقوا به و—-جاء ابو بكر فاخبروه فاتبعهم فرد عليهم القلاءص واخذه فلما قدموا علي النبي صلي الله عليه وسلم اخبروه فضحك هو واصحابه منهما- حولا |

Passim was developed by David Smith and his team for the purpose of detecting instances of text reuse in a large corpus of nineteenth-century American newspapers; see their project website: viral texts. In this case, passim treated each newspaper article as a document for comparison, meaning that each compared document was around 2,000 words or fewer.

This approach was inappropriate for the texts in KITAB’s corpus for two reasons. First, the texts in the OpenITI corpus are typically very large. And second, text that is reused between works in the OpenITI corpus is often rearranged. KITAB, therefore, pre-processes the OpenITI texts before running passim by splitting them into 300-word chunks (termed milestones and marked by ‘ms’ and a number in OpenITI texts; for example, ‘ms120’). Each chunk is then treated by passim as a separate document.

In practice, therefore, passim compares every 300-word chunk of each work with every 300-word chunk of every other work and identifies chunks that share text. Smith-Waterman is then used to create alignments between those chunks.

Together with KITAB, Ryan Muther has developed a further approach to running passim on KITAB’s texts, which we term aggregation. Sometimes text reuse crosses milestone boundaries. In these cases, reused text at the edge of the milestone may be missed. Aggregation reassembles the milestones in such cases to create larger alignments that better represent the full extent of the reuse between the two works.

Whether normal or aggregated passim data is more helpful in any given situation depends on the type of analysis or visualisation, so we produce both types of data sets.

Read more about how passim works in this paper: David Smith, Ryan Cordell, Abby Mullen, Computational Methods for Uncovering Reprinted Texts in Antebellum Newspapers, https://viraltexts.org/2015/05/22/computational-methods-for-uncovering-reprinted-texts-in-antebellum-newspapers

What does our passim data look like?

The result of the above process for any pair of texts is one csv (comma-separated value) file in which each row represents an individual alignment.

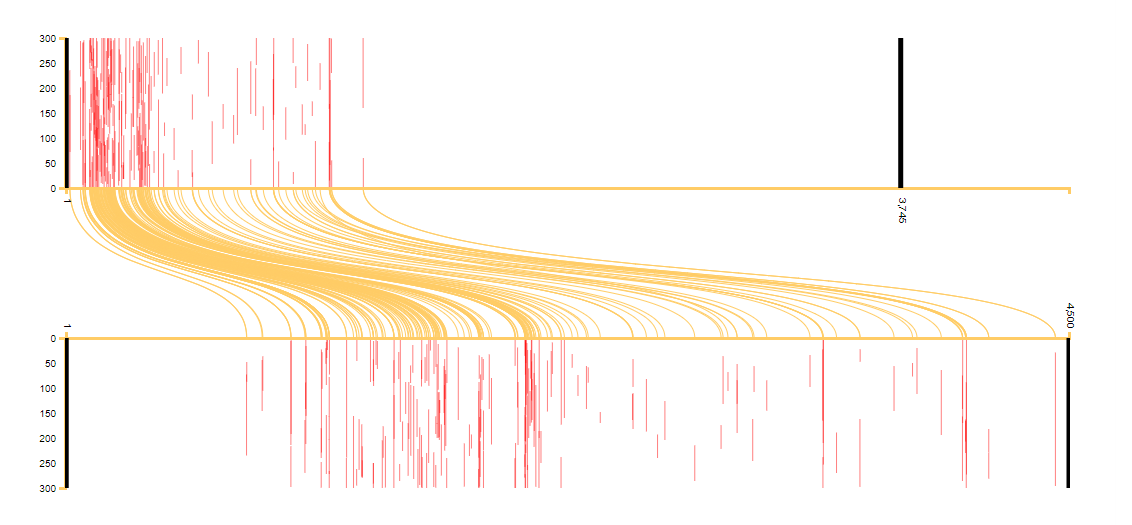

This individual alignment file can then be viewed using KITAB’s alignment reader (see Figure 1), which helps us visualise how text is shared between a pair of works.

Figure 1: A visualisation comparing Ibn Taghribirdi’s (d. 874/1470) Nujum al-zahira on the top with Ibn al-Athir’s (d. 630/1233) al-Kamil fi al-taʾrikh on the bottom. Yellow lines indicate reused text, and the red bars show the length of each instance of reuse. One can clearly see how Ibn Taghribirdi condensed the Ibn al-Athir’s material when writing his chronicle, as both chronicles end with their author’s lifetimes. For more on the visualisation, see here.

From these alignments we also compute statistics for each book (again for both normal and aggregated data) that show, for example, what proportion of a work is shared with another work and how many words are shared between two texts. This statistical data is fed into a Power BI application, and it is also used by team members to investigate research questions.

Improving passim

A number of decisions must be made when running passim on the whole corpus. We have chosen to split our texts into 300-word chunks (rather than, say, chunks of 100 words). And we have selected a set of parameters that we think are best suited to identifying text reuse in classical Arabic.

These decisions are subject to constant review, and we are producing alignment data sets that have been checked by team members to test and experiment with new parameters and approaches. For an idea of how we review passim, see this blog post.

Passim FAQs

When does KITAB run passim?

We run passim at least twice every year to account for corpus changes. We do not run it more frequently because the preparation of the corpus and subsequent analysis of the data produced by passim is very time-consuming. It is important for us that the corpus is prepared appropriately and that the data and subsequent results are checked thoroughly to guard against potential errors. Each time passim is run, the current version of the corpus is released on Zenodo, so that the text reuse data can always be traced back to the state of the corpus at the time passim was run. See further our explanation of corpus releases.

Can I access the passim data?

At present we are not releasing the passim data publicly. This is because we are still developing and improving our processes for running passim and analysing its output. We hope to release the data soon, and when we do we will also release a suite of applications to help researchers make the most of it. We are currently sharing the preliminary data sets with those who are working with us to expand the corpus and interpret our data.

Can I run passim?

It is possible to run passim on any computer on a small corpus of texts. To run the algorithm on larger quantities of text requires a huge amount of computing power, and accordingly we run it on the OpenITI corpus using a server.

Using passim is not recommended unless you have a good familiarity with computers. Instructions for how to run passim can be found here. A development branch of passim now allows you to run the algorithm through Python, and this is the recommended route. For instructions, see here.