Post 7: Text Reuse Alignments

How did al-Tabari create his extensive works? We contend that well-organised sets of notes played a critical role. Our argument relies on reasoning about the practicalities of working at scale, as well as our analysis of a data set consisting of thousands of citations that al-Tabari begins with the formula ‘he told me’/’he told us’ (haddathani/haddathana). As demonstrated in previous posts, we have counted and tabulated these people who, he says, gave him information and have sketched visually (through tree maps) the bundles of notes he likely copied down and collated into notebooks.

We can also draw on text reuse alignments. As evidence, these are of an altogether different character and derive from a different data set. The alignments that we have identified between al-Tabari’s Taʾrikh al-rusul wa-l-muluk, Jamiʿ al-bayan ʿan taʾwil ay al-Qurʾan (Tafsir) and Tahdhib al-athar (files Shamela0009783BK1, Shamela0007798 and JK008250Vols in the OpenITI corpus, respectively) consist of 1,374 rows in which a passage of at least ten words in one of the works overlaps with a passage in another of the works. The books are divided into chunks of 300-word tokens, so the maximum length of an identified alignment is 300 words. The largest share of the alignments found is between the Taʾrikh and the Tafsir (1,101), but there are also significant alignments between the Tafsir and the Tahdhib (229) and a few between the Taʾrikh and the Tahdhib (44). Of the alignments between the Taʾrikh and the Tafsir, 258 contain 100 words or more, and 54 exceed 200 words.

The algorithm that generated these alignments is called passim, and it is able to find aligned text passages rather well. For example, it recognises alignments even if the overlapping passage runs continuously in one text but contains additional insertions of phrases, names or other words in the other text.

Even short alignments often point to a shared source. The following brief alignment between the Taʾrikh and the Tafsir, provides an example. Differences are highlighted, and dashes mark a word missing from one of the parallel texts. Even without knowing Arabic, one can see that the differences are not substantial in terms of quantity. Both alignments begin by citing Ibn Ishaq.

Taʾrikh, milestone 66:

ابن اسحاق قال يقال والله اعلم خلق الله ادم ثم وضعه ينظر اليه اربعين يوما قبل ان ينفخ فيه الروح حتى عاد صلصالا كالفخار ولم تمسه نار قال فلما مضي له

Tafsir, milestone 292:

ابن اسحاق \-\--فيقال والله اعلم خلق الله ادم ثم وضعه ينظر اليه اربعين عاما قبل ان ينفخ فيه الروح حتي عاد صلصالا كالفخار ولم تمسه نار قال فيقال والله

In the Taʾrikh, the passage is found in a section dedicated to the topic of Adam’s creation (al-qawl fī khalq Ādam), and it is preceded by an isnad going back to Muhammad b. Humayd (d. 248/862). The report begins with ‘Ibn Ishaq said’. The following translation loosely follows Rosenthal’s:

Ibn Ishaq said, reportedly (God knows best!), that God created Adam, then put him down and looked at him for forty days before blowing the spirit into him, until he became ṣalṣāl like potter’s clay untouched by fire. [Ibn Ishaq] said that once [that period] had passed …

In the Tafsir, Ibn Ishaq is cited without an isnad, and the word ‘said’ that follows his name in the Taʾrikh precedes it, thus falling outside the alignment. More critically, in the Tafsir’s version, God looked at Adam for forty years rather than forty days (ʿāman versus yawman). The passage appears in the context of commentary on Quran 2:30: ‘When your Lord said to the angels, I am putting a successor (khalīfa) on earth, they said, “Will You place someone there who will cause corruption on it and shed blood, while we glorify You with Your praise and extol Your holiness?” [God] answered, “Surely, I know that which you do not know.”’1

There are numerous such closely related passages, and once passim has identified and output them into a CSV file, we can spot their differences. But in its current form, passim does not capture paraphrase unless it occurs within a chunk that otherwise aligns. In general, this means that we have a harder time finding evidence of reuse when an author actively revised the source text into his own.

In the longest alignments between the Taʾrikh and the Tafsir, both texts rely heavily on Muhammad b. Humayd’s transmission of Ibn Ishaq’s Sira. In fact, of the ten longest alignments, all but one can be traced to Muhammad b. Humayd. The Sira – as passed on by Muhammad b. Humayd – represents a major source common to all three of al-Tabari’s works.

Beyond Muhammad b. Humayd, we find other direct informants. As an experiment, we searched through the passim output files for the surface forms of the ten most often cited direct informants. Of the 1,374 alignments, 555 contain one of the names – and in fact all ten top informants are named. Although this evidence is not extensive, it does suggest that al-Tabari reached back to the same trusted notebooks for his different works.

Not Copying Between Works

The general picture of text reuse yielded by our data set is one of a few extensive alignments and many more fragmentary ones. The most obvious explanation for this phenomenon is that al-Tabari used a common set of notes but adapted them differently in different contexts.

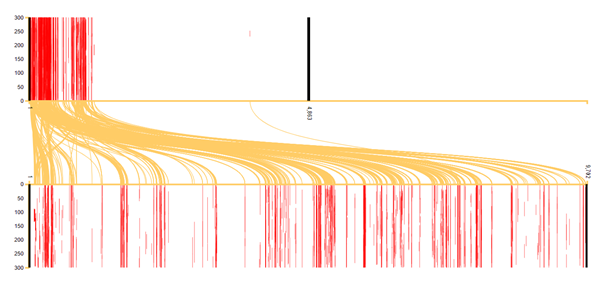

Previous scholars have held the view that al-Tabari did not copy wholesale the Tafsir into the Taʾrikh (or vice versa), and that is also what our data and visualisations suggest.2

Image 1: Alignments between the Taʾrikh (on the top) and the Tafsir (on the bottom). Based on passim run of February 2021. Files compared: Shamela0009783BK1 and Shamela0007798.

Image 1: Alignments between the Taʾrikh (on the top) and the Tafsir (on the bottom). Based on passim run of February 2021. Files compared: Shamela0009783BK1 and Shamela0007798.

The latest section of the Taʾrikh that is aligned with the Tafsir falls within a discussion of events in the Prophet’s lifetime, specifically concerning the Prophet’s wife ʿAʾisha. The arrangement owes much to Sira material derived from Muhammad b. Humayd, and the frequency of mentions of Muhammad b. Humayd’s name in the aligned passages also points to both texts relying heavily on the Sira.

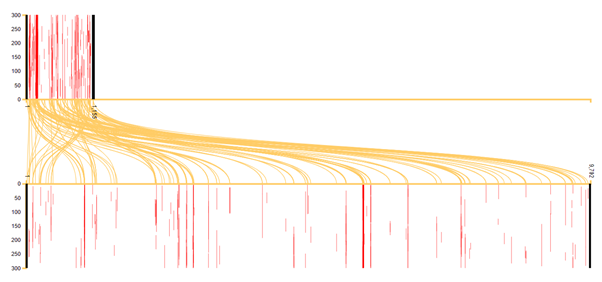

Image 2: Alignments between the Tahdhib (on the top) and the Taʾrikh (on the bottom). Files compared: JK008250Vols and Shamela0009783BK1.

Image 2: Alignments between the Tahdhib (on the top) and the Taʾrikh (on the bottom). Files compared: JK008250Vols and Shamela0009783BK1.

By contrast, there are very few alignments between the Tahdhib and the Taʾrikh, and no obvious pattern. The total number of aligned passages between these two works is forty-four, and the longest passage consists of 239 words. Eight further alignments contain 100 words or more.

Image 3: Alignments between the Tahdhib (on the top) and the Tafsir (on the bottom). Files compared: JK008250Vols and Shamela0007798.

Image 3: Alignments between the Tahdhib (on the top) and the Tafsir (on the bottom). Files compared: JK008250Vols and Shamela0007798.

Between the Tahdhib and the Tafsir, there are a total of 229 aligned passages, the longest of which is 265 words. Of these alignments, forty-five contain at least 100 words.

In view of the most closely aligned sections in the two works, it is possible that al-Tabari used some short sections of the Tahdhib al-āthār to write up a few parts of the Tafsir, for example. Such consultations though would be few, if any at all. The general pattern and imprecision of the alignments do not support the conclusion that this was his primary modus operandi.

In our final blog post, we bring our exploration to a close with a brief but important reflection on how al-Tabari himself became a direct informant.

-

Our translation loosely follows Wahiuddin Khan’s. ↩

-

E.g., Franz Rosenthal, general introduction to al-Tabari, The History of al-Ṭabarī, i: General Introduction and From the Creation to the Flood, trans. Franz Rosenthal (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 80–134 (where he combs the biographical sources). ↩