Machine-learning-based approaches are at the cutting edge of the Digital Humanities. KITAB is using this approach in a field that we call ‘subgenre classification’, which is being developed by Ryan Muther. By ‘subgenre’ we mean distinct units in a text that share certain characteristics that can be distinguished. These are the kinds of features that we as human readers can easily identify on the basis of our understanding of how a text works. Examples include isnads, poetry and Quranic quotations. It is useful to be able to identify subgenres that occur frequently across the corpus, a task that would be impossible to undertake manually for the more than 6,000 texts in our corpus.

The identification of subgenres can help us address research questions such as the following:

- Does the frequency of isnads in texts vary over time?

- How long are isnads, and do they get longer or shorter over time?

- Where and how often is poetry quoted in a text? Do certain texts quote poetry in similar ways?

- How common is Quranic quotation in the corpus?

Automatic isnad detection: Our first case study

So far, we have attempted automatic detection of one subgenre: isnads. The ability to detect isnads automatically across the OpenITI corpus is valuable for multiple reasons. First, it helps us better understand how these lists of names, which are repeated frequently throughout our corpus, interact with text reuse detection. We know that at least some of the instances of text reuse identified by passim are only alignments of long isnads without shared matns. Second, identifying isnads allows us to analyse the names and the networks of scholars that they represent. Automatic isnad detection has also given us a better understanding of the OpenITI corpus and guided our research into book history. For examples, see our blog posts that engage with the isnad data set.

On this page, we will provide a relatively detailed overview of how the automatic detection of isnads works. This is our first machine-learning workflow, and it will help inform our implementation of other machine-learning-based methods in the future.

The process: Training and retraining the model

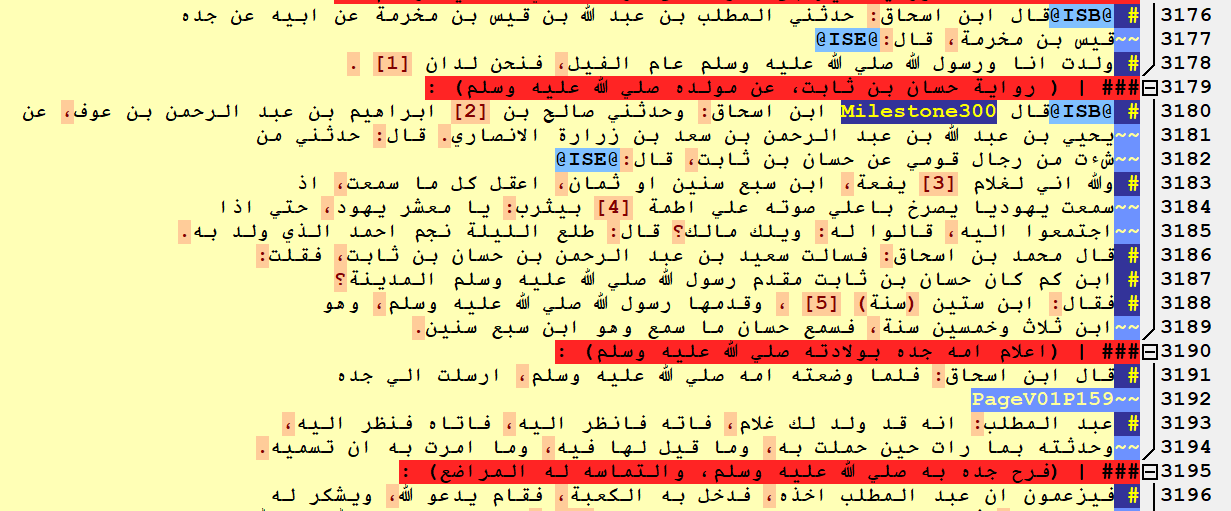

The first step was to create training data for the model. A number of team members (the annotators) worked together to read a variety of OpenITI texts and insert two types of tags into the text: \@ISB@ to mark the beginning of an isnad and \@ISE@ to mark the end of an isnad. The annotators studied 2,000 lines in each text that they worked on, spreading their annotations throughout the text (for example, they might look at 200 lines, skip 1,000 lines, look at another 200 lines, and so on until they had looked at 2,000 lines in total). By logging the lines that they studied, the annotators provided both positive and negative feedback for the model. For example, if the annotator found no isnads in one set of 200 lines and did not add any isnad tags to it, the model would know that it should not identify any isnads in that section.

Image 1: A screenshot of Ibn Hisham’s Sira in EditPad Pro with the beginnings and ends of isnads annotated.

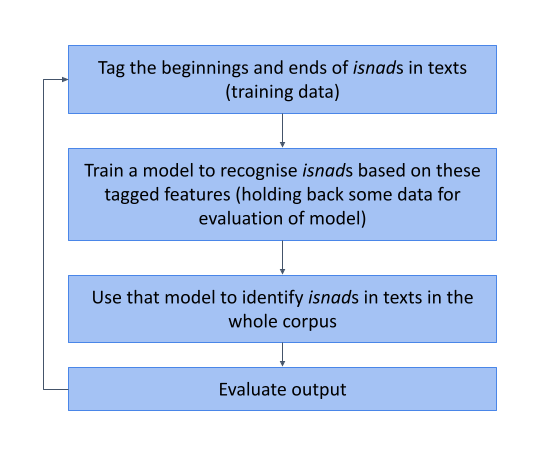

Once some texts had been tagged, Ryan Muther, the computer scientist working on the isnad classifier, used those texts and their tags to train the isnad-classifier model. The newly trained model was then used to identify isnads in texts without tags, and this data was used to insert beginning and end tags into the text.

The annotators subsequently evaluated the machine-inserted tags, moving, deleting or inserting tags as needed. At the same time, the annotators made observations about the positions of the machine-inserted tags and the general quality of the automatic detection. These observations helped guide the creation of more training data by, for example, prompting the annotators to tag more texts of a certain genre.

Image 2: A flowchart illustrating the process of annotation and review used to train the isnad detector.

Inter-annotator evaluation

When training a model, it is important to know how difficult the task is for a human annotator. If human annotators struggle to agree on an identification, the machine will also have difficulties with this task. To this end, the annotators undertook an inter-annotator agreement study at the beginning of the process. All annotators were asked to identify and tag the beginnings and ends of isnads in the same locations in the exact same text. The annotations were then compared. This study found that the annotators largely agreed on the starting positions of isnads but disagreed on where they ended. The model also had similar difficulties identifying the ends of isnads.

How does the algorithm work?

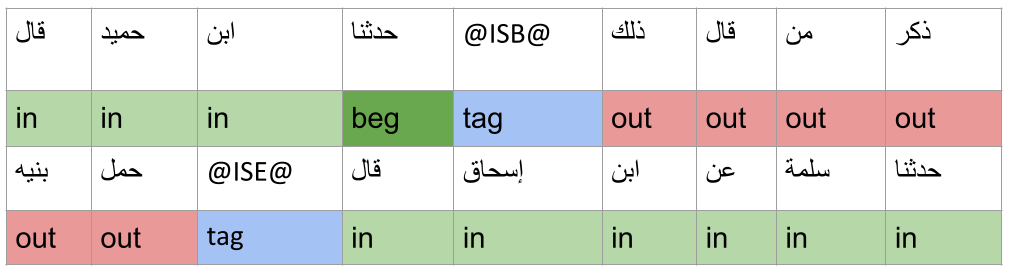

Put simply, the algorithm learns to identify the position of isnads by recognising the kinds of words that are common to isnads and the kinds of words that are more commonly found outside of isnads. In addition, it identifies words that commonly start isnads. Table 1 illustrates how the model classifies sample words in the training data set.

Table 1: Examples of how the model would tag certain words in the training data. ‘Out’ means outside of an isnad, ‘in’ means inside an isnad, and ‘beg’ means the first word of an isnad.

The quality of the results

When training the model, a small part of the training data is kept back to be used as unseen data to evaluate the model’s performance. The algorithm was trained multiple times, with a different portion of the training data withheld each time for evaluation. Its performance on this unseen data was then averaged to produce a score for the algorithm.

We used two scores to evaluate the model: precision and recall. Precision measures the degree of agreement between the model and the unseen training data. Low precision means the machine identified isnads where, according to the training data, there should not have been any. Recall measures the proportion of isnads in the unseen training data that the model found. Low recall means that the machine failed to identify many of the isnads tagged in the training data.

At present, the precision of the model is .873 and the recall is .804. These are considered good scores and mean that we can trust the model’s outputs – to a certain extent; for caveats, see below.

Challenges

Identifying isnads at the corpus level involves a huge number of challenges. Chief among them is the fact that we cannot check the results of the algorithm in every text. Although the algorithm scores highly in both precision and recall, these scores are based only on the training data that we provided the model. Certain genres (such as history and hadith) were better represented than others in our training set, and this imbalance risks biasing the model. The team aims to continue training and improving the model, but the success of these efforts will also depend on the continued expansion of the OpenITI corpus to include a wider variety of genres and on the improvement of our metadata to enable focus on different types of texts.