In previous posts, other members of the KITAB team have talked about building the OpenITI corpus of Arabic and Persian sources. Many members of the team are also working to build better optical character recognition (OCR) systems in the Arabic-script OCR Catalyst Project (AOCP). The better we can automatically turn images of printed Arabic into machine-readable texts, the better we can help readers and researchers find and engage with these texts. OpenITI and AOCP, we shall see, are complementary in several ways. Under different guises, they are also both examples of that oldest of undertakings of the humanities: textual criticism.

What do we need to build an OCR system? Most of today’s systems use supervised learning. When building the OCR system, we compile pairs of images and the text contained in those images and then use a machine learning algorithm to adjust the system’s parameters in response to these desired input-output pairs. In general, these algorithms work by adjusting the parameters more drastically on those examples where the system performs particularly poorly.

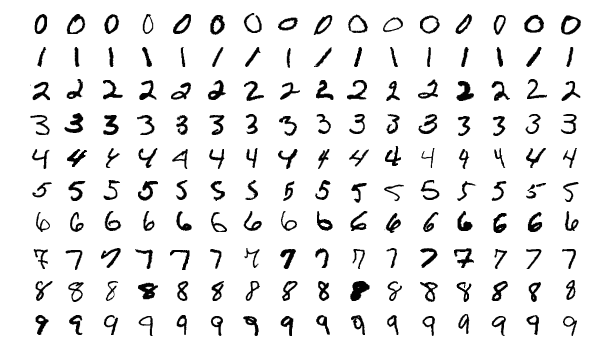

What kinds of images should we use for training OCR? For many languages and applications, the answer was to employ isolated characters, as in the MNIST database of images for handwritten digit recognition, a widely-used benchmark in computer vision.

For ten numerals, or writing systems with a few hundred letters and special characters, this might be an attractive strategy. For connected scripts like Arabic, however, training systems with isolated characters has some drawbacks. Even if we catalog variant initial, medial, and final forms in one typeface or manuscript hand, we would need to segment the images, as well, which is much more time consuming. Similar issues arise in speech recognition, where the distinct “phonemic” sounds of a language change their sound depending on surrounding sounds and our lips might be forming the next sound when our tongue is still tapping our teeth for the last.

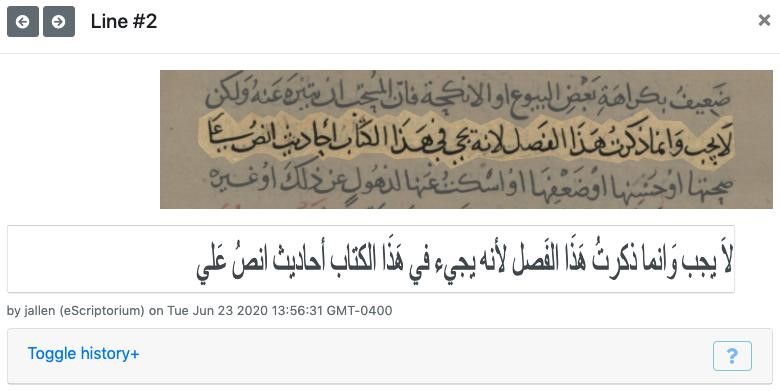

Instead, OCR (and speech recognition) systems can take advantage of algorithms that align complete lines of writing with transcriptions of those lines. It is much easier to ask human annotators (and computer vision models) to mark full lines than to delimit where one cursive letter ends and the next begins. This is even more true in writing systems such as Arabic, where characters also overlap in the vertical dimension, as in this manuscript example:

In the eScriptorium annotation tool, the upper image highlights one line of the manuscript, which the user has transcribed in the lower panel. We can send this selected image region and transcribed text to the Kraken OCR engine to train a new system.

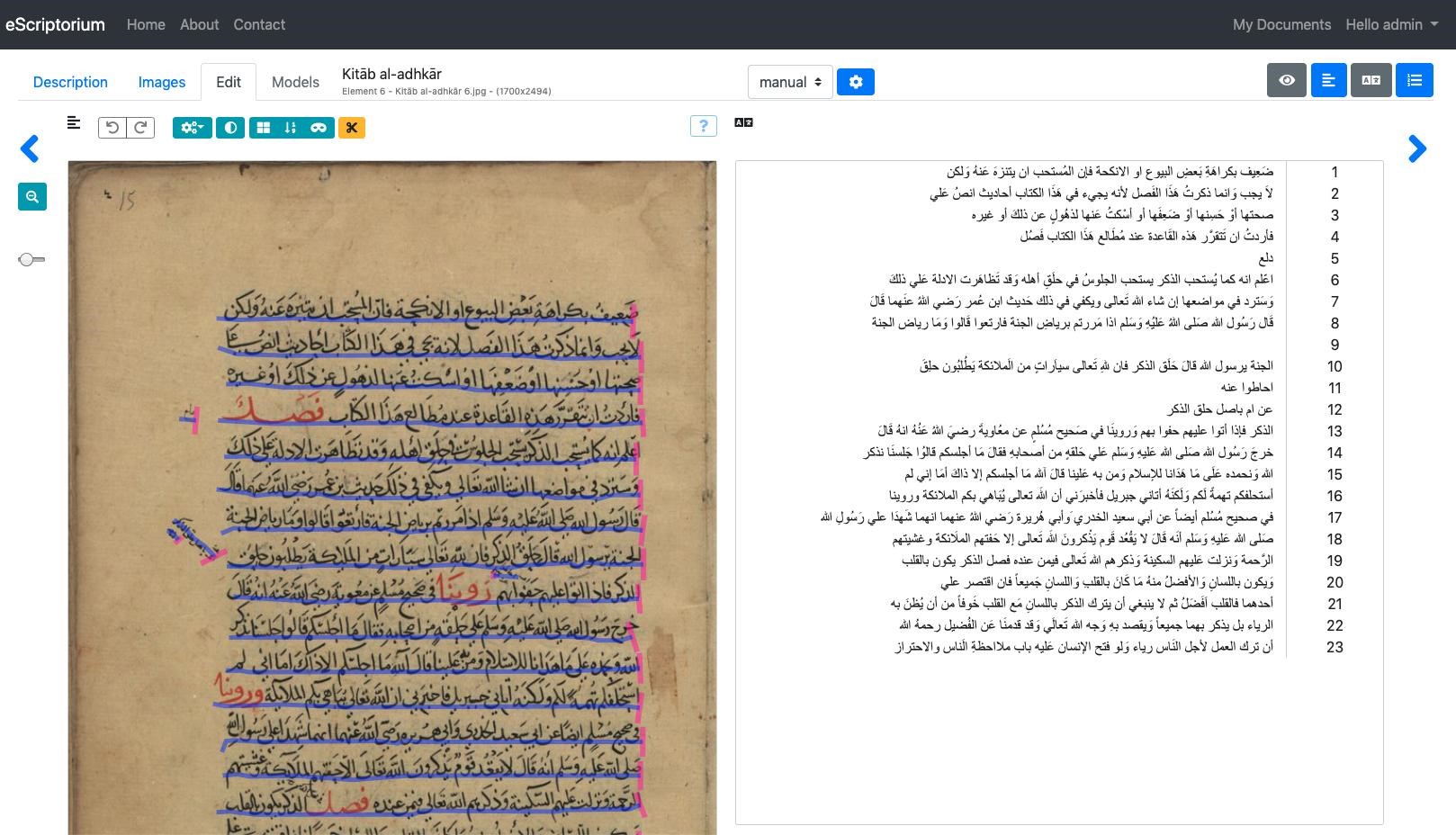

It’s convenient that we can avoid the tedium of segmenting one Arabic letter from the next—or even each word from the next—on a line of type. And it’s especially convenient that automatic line-segmentation models can break a page image into lines without much need for user correction. (The blue underlines in the image below show some of Ben Kiessling’s recent work on Kraken.) But what about the remaining task? It still sounds like a lot of work to type the contents of each line to tell the OCR system what output it should get from each input line image.

This is where our ongoing work on the OpenITI corpus can help. Rather than asking, What is the transcription for this image?, we can ask, Are there any images that correspond to this text we’ve already transcribed? As in many machine learning scenarios, there is a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem here. In order to find images that correspond to OpenITI texts, we need some information about those images. As it happens, for many typefaces, we can train an OCR model that transcribes 50% or 60% of a book’s characters correctly using only a few thousand lines of cleanly-transcribed training data. We can then apply this model to images to produce approximate transcriptions, or use already existing noisy OCR output from sources such as the HathiTrust library of scanned books. We then employ the same passim software we use elsewhere in the KITAB project to identify text reuse among books. This gives us an alignment between the clean transcription in OpenITI and the noisy transcription from the OCR. Importantly, the OCR output tells us where on the page each line is. We can thus infer that clean, OpenITI text that aligns to dirty OCR is an approximate transcription for that line. Such pairs of clean transcriptions and line images are precisely what we need to train better OCR systems. I’ll leave aside for now some other aspects of our OCR work, such as locating different page regions, from notes to marginalia, to running headers, on the basis of OpenITI annotations.

I’ll close by considering how OCR and other technologies relate to more traditional methods of producing editions of ancient texts for us to read. When we read, in print or on the screen, texts that were written before the age of mechanical reproduction, we know that someone, perhaps centuries after the original manuscript, made choices about what to print. Even before the advent of systematic textual editing, let alone editing with computer models, enthusiasts like Petrarch hunted for manuscripts of ancient texts so they could read them. Copies made by enthusiastic amateurs sometimes provide our only evidence for some ancient works. While it’s not the case that Shamela and other community archives preserve texts found nowhere else, it is helpful, I think, to consider them as manuscript sources. OCR transcriptions of digital page images, for all their flaws, can also be considered “editions” (as my colleague Ryan Cordell argues) or again, as I would argue, the source material for editions in the OpenITI. The process described above of aligning texts in the OpenITI corpus with noisy transcriptions produced by OCR is thus a form of textual collation, the system by which textual critics organize the evidence of their sources in order to produce an edition.

Like textual criticism, therefore, OCR is a technology that helps us go from less accessible source materials to texts searchable, readable, and usable by a wider audience. This work, for printed books and manuscripts, is still ongoing, and we hope to share more in the future.