On 2 January, we began a new European Research Council-funded project, ‘KITAB-Transform’ (ERC, grant no. 101199672). We hope that scholars will join us on what promises to be a new and exciting adventure into machine learning and Natural Language Processing for Classical Arabic.

With our first phase, KITAB (ERC, grant no. 772989), we adapted and applied the text reuse detection algorithm passim to the OpenITI corpus. We were able to map millions of matches across our corpus, and to create the web application through which scholars can access our data, results and visualisations, and also explore the corpus to trace relationships between books.

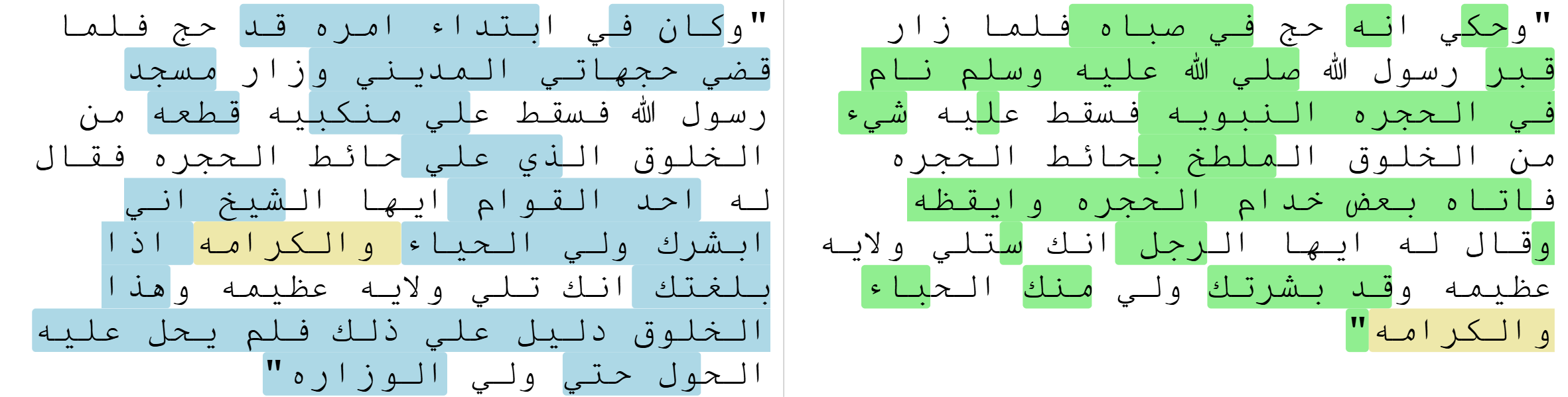

Figure 1: This is an example of text reuse with a transformation, in the KITAB diffViewer (unhighlighted text is common between both passages; text highlighted in blue and green is different in both passages, text highlighted in orange is shared but in different locations).

Figure 1: This is an example of text reuse with a transformation, in the KITAB diffViewer (unhighlighted text is common between both passages; text highlighted in blue and green is different in both passages, text highlighted in orange is shared but in different locations).

Now the team is developing upon advances in machine learning and natural language processing to understand how medieval authors writing in Arabic and Persian used paraphrase and translation to produce their books. This sort of ‘transformative’ text reuse eluded passim, which only detected near-verbatim text reuse.

For historians, this research promises to yield a new methodology that we will develop in our publications and online resources. To illustrate, these are the sorts of questions we will be addressing in the coming years.

-

Minor Paraphrase: Authors often reuse text or ideas from earlier works by rephrasing it to a greater or lesser degree, that is, using more or less of the same words. Since such paraphrase appears alongside the near-verbatim text reuse, we can use passim to detect environments in which paraphrase is likely to appear.

-

Summarization: A specific form of paraphrase in which the original text is significantly shortened. We are interested in classifying the strategies authors used to do this, and in mapping these strategies over time, space, and genres.

-

Paraphrase of the Qur’an: The Qur’an is usually cited word for word, without changes. Verbatim quotations of the Qur’an are so common that KITAB’s passim algorithm often overlooked them as mere formulae. However, Qur’anic verses are also sometimes paraphrased, for example for the purpose of explicating them, and our planned model will offer the first opportunity to research the extent of this practice at scale.

-

Versification: Authors writing in a wide variety of fields (medicine, grammar, logic and Qur’an recitation, to name only a few) versified manuals and standard works to help students memorise and internalise the most important tenets of the discipline. Such versifications paraphrase and condense the original text and subjugate it to metre and rhyme.

-

Arabic-to-Persian translation (book-length translations): Works translated in their entirety showcase a variety of transformative strategies employed by translators. We will use a subcorpus of translated geographical and historiographical texts to describe the writerly practices of Arabic-to-Persian translators. We will also assess whether the practices we document in our subcorpus are common elsewhere in the corpus.

-

Passages translated from Arabic and embedded in Persian texts: Detecting shorter translated passages within Persian texts is more difficult. We will refine the model developed for book-length translations to identify these shorter passages in Persian texts that are not full translations of an Arabic original.

-

Aural intermediaries: When an author cites a passage from a work that was transmitted aurally, the aural intermediaries are often named in the isnād, the chain of transmitters that links the written version of the work to its original source. Comparing later quotations of a text with (versions of) the original text at scale will enable us to answer questions about the degrees of variation introduced by these aural intermediaries.

-

Lost intermediaries/sources: The work of KITAB demonstrated how text reuse can in fact cause loss of texts, as later books replace older ones. Reuse analysis allows us to glimpse fragments of lost sources in later works, but the sources were not always copied verbatim. Being able to identify fragments of otherwise lost texts even if they have undergone transformative reuse will help historians gain a better picture of important works that no longer survive.

-

Anonymous texts with a high degree of textual variance: Many works of unknown authorship survive in multiple versions. Trying to identify an ‘original’ text is usually futile, but studying the relationships between different versions can tell us a great deal about the transformative processes at play.

-

Devotional poetry: Poetry devoted to religious figures often contains stories and ideas that are also found in more scholarly genres, such as biographies and theological works. These stories and ideas often cannot be traced back to a specific source; instead, they may derive from a cultural memory shared by the community. We will explore this issue by analysing devotional poetry on the Prophet Muḥammad and Druze devotional poetry.

We will publish an online report for each case study. We will also release the pertinent data through Zenodo. Our reports and other publications will address the following book history questions – plus more as we work our way through the cases:

-

Authorial practices: How do authors purposefully transform earlier material to produce a new work? Can we trace changes in these practices over time, space and genre?

-

Changing forms of the book: What notion(s) of ‘the book’ shaped authors’ transformations of earlier texts?

-

Narrative adaptations: To what extent were past texts considered a plastic resource? What were the limits of transformation?

If you are interested in any of these cases, please do get in touch already. We will add cases, too, and you might have ideas to suggest.

Under the Hood

A key advance that will facilitate our work is the development of sequence embeddings, which have revolutionised the computational study of language, especially since the arrival of the BERT language model (2018). A sequence embedding converts words and sentences into an abstract representation, with each word or subword encoded according to its usage in the relevant language as a vector of numbers. These number vectors function like the geographical coordinates of places: comparing the coordinates of any two places on earth makes it possible to calculate the distance between them. Whereas geographical coordinates are vectors of only two numbers (latitude and longitude), embeddings typically entail vectors of thousands of numbers; but like coordinates, they allow us to calculate the (semantic) distance between two points – in this case, words or sentences. Because a word, its synonyms and its translation are all likely to be embedded in a similar manner, sequence embeddings have already shown great promise for identifying instances of transformative reuse, even across languages. We believe that when applied to the OpenITI corpus, they can reveal a layer of textual relationships and patterns that have hitherto remained invisible. Uncovering the role of transformative reuse in the creation of the Arabic textual tradition will give us a fuller understanding of authorial practices, the history of the Arabic book and its impact on cultural memory.

Our cycle of model building and evaluation is now proceeding according to the following plan: we start with a working definition of a transformation (these are typed, e.g., summarization, book-length translations, transmission via oral intermediaries), including feature delineation, emic/etic descriptions, and anchor examples. We discuss and document how the transformation can be modeled, and what evaluation data is needed to test the model. We then collect machine-actionable texts into a sub-corpus and generate training and evaluation data by annotating instances of the transformation, updating the theoretical model as we do so. The team collectively trains the computational model, runs it on the sub-corpora and compares the results to the evaluation data to assess the model’s performance relative to human judgement. The method includes human annotators’ explanations of relationships between pairs, with the goal that the model will in the future generate the justifications for alignments.

We have begun already with summarization and using passim to detect instances of paraphrase near more verbatim reuse. Stay tuned for updates as we proceed!