“How can I bear to pair fair words in rhyme

when I have lost the one with whom I was a pair?”1

So mourns the great Mamluk-era poet Ibn Nubata al-Misri (d. 768/1366) his deceased concubine. She was but one of the many family members the poet lost throughout his long life: he is said to have lost no less than sixteen sons who were between the ages of 5 and 7.2 While this particular concubine died because of pulmonary tuberculosis, presumably a good number of his sons died of the devastating effects of the plague, also known as the Black Death. This most famous of pandemics is estimated to have wiped out half of Egypt’s population in the mid-eighth/fourteenth century. Its persistence in North Africa until quite recently may even have indirectly inspired Albert Camus’s classic novel La peste (The Plague).3

The recent outbreak of Covid-19, while serious, is fortunately nowhere near as dramatic as the onslaught of plague pandemics in the medieval world was. Nor is it as deadly as the cholera epidemics of the nineteenth century that probably inspired Camus more directly. But these curious times do invite us to ponder the lessons and warnings (ʿibar, sg. ʿibra) of history, one of history’s primary roles according to many medieval Muslim historians. I started wondering in what ways the OpenITI corpus can tell us something about the impact of the plague in texts. The development of a new OpenITI NgramReader+ by our team’s senior research fellow Maxim Romanov provides an opportunity to do so, as it allows us to gain a snapshot idea of the usage of Arabic terms across the centuries.4 The reader exists in three forms: a ‘Lite’ version, which provides data on unigrams (i.e. single words) only, as well as ‘Medium’ and ‘Full’ versions, which also include bigrams (i.e. two words). The Lite version is accessible online and will be used here. The other versions can only be run on a local machine. All three versions of the app can be downloaded here.

To quote Maxim, the NgramReader+ ‘charts diachronic frequencies of words and phrases, using the data of the OpenITI corpus (Arabic data only)’. The data from the corpus is grouped in half-centuries according to authors’ death dates. Once prompted, the reader will give you data on the absolute and relative frequency of the selected words in two separate graphs. As you will notice, this requires getting the hang of particular transcription rules and some basic notions of regular expressions. The data provided is only abstract, as at the moment it is not possible to locate the usages of these terms in precise texts. However, work is currently being undertaken by Sohail Merchant and Peter Verkinderen on a complex search app which will allow readers to locate (variations of) particular words and phrases.

The Arabic sources confront us with two terms used somewhat interchangeably for the plague: taʿun and wabaʾ. This is no problem for our purposes, as the great thing about the NgramReader+ is that it allows you to run searches for up to five terms at once. I put both these terms into the Ngram prompt. What emerged is that neither taʿun nor wabaʾ have a very strong presence in our corpus, but that logical trends in their usage seem to be discernible. Logical, because the peaks of usage for these terms appear to follow the eighth/fourteenth and ninth/fifteenth centuries, when the pandemic hit repeatedly throughout the Middle East.

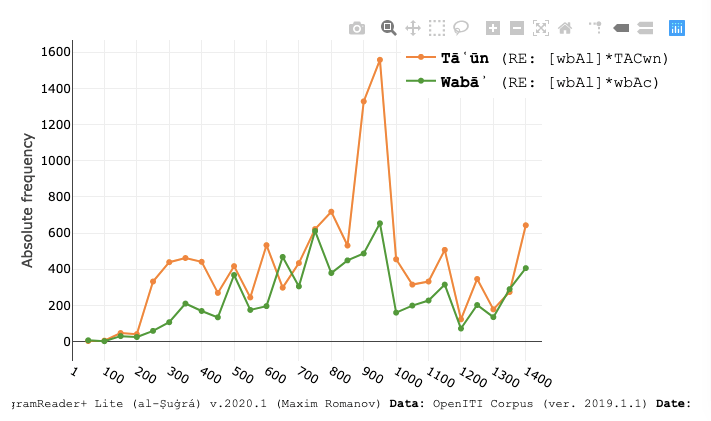

Figure 1: The absolute frequency of taʿun and wabaʾ in the corpus by half-century.

The graph in Figure 1 provides absolute numbers for term occurrence, showing that taʿun peaked in the late ninth/fifteenth and early tenth/sixteenth centuries, and that wabaʾ experienced a sharp drop-off after that period. One of the possible reasons for this is that the ninth/fifteenth century especially saw a huge boost in textual production, especially historiography, much of which would have been retrospective. Some of the richest sources on the eighth/fourteenth-century plague were produced not at the time of that pandemic but in the following century. Furthermore, the early Ottoman period also saw several pandemic periods.

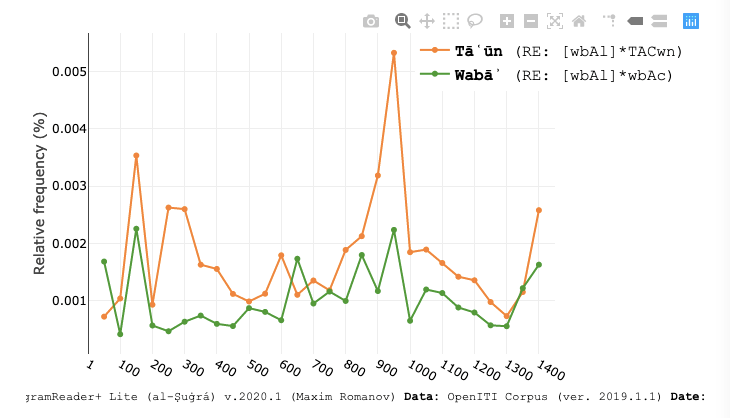

Figure 2: The relative frequency of taʿun and wabaʾ in the corpus by half-century.

The graph in Figure 2 shows the relative frequency of the terms compared to the total word count for each half-century. This shows that neither term was used very often, as the percentages are very low. Considering that any word is indexed as an Ngram, however, the percentages will always be quite low as commonly used words take up much of the space. This graph provides us with a glimpse of another peak in the early centuries, coinciding more or less with what has been called the Justinianic Plague (c. 541–750 CE), the first historically documented plague outbreak. Because of the smaller size of our corpus for these centuries, the absolute numbers are low here, but in relative terms there is a discernible pattern.

Such results can be fine-tuned considerably in the app, and they can also be combined in longer phrases (bigrams – though these can be accessed only via the Medium and Full versions of the reader), but I have chosen here to focus only on a quick demonstration of its abilities. Likely the most important caveat for this mini-exploration is that some of the main sources for this subject are not (yet) part of our corpus. Firstly, we appear to have none of the so-called plague treatises in our corpus despite their relative prevalence in Arabic literature (about three dozen are known). Secondly, medical literature is not particularly well represented either. This little blog excursus of mine has thus brought to attention a few lacunae in our corpus, which can be addressed through our OCR pipeline.

The plague treatises generally follow a form that is familiar in our corpus: they are patchworks of various citations, especially from prophetic Hadith, compiled as relevant information on a particular topic. While some provide medical and historical data on the plague, the treatises mostly argue that the grief caused by the plague should be weathered by showing patience (the important Islamic virtue sabr) and that one should be reconciled with God’s designs for humanity. Three such plague treatises have received a fair amount of scholarly attention. One was written by the eighth/fourteenth-century littérateur Ibn Abi Hajala (d. 776/1375), from whom we have only one work in our corpus at the moment (a grave underestimation of his literary importance). Another one was written by his contemporary Ibn al-Wardi (d. 749/1349), from whom we similarly have only one work in the corpus. A third text was written by the ninth/fifteenth-century scholar Ibn Hajar al-ʿAsqalani (d. 852/1448), from whom we have many works in the corpus, but with somewhat inordinate stress on his traditionalist, historical and legal writings. This last text was later abridged and annotated by one of the most prolific authors in Arabic literature generally speaking, Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti (d. 911/1505). His writings are also well represented in our corpus, but his plague treatise is not available.

As a further excursus into book history in its manuscript form, I would like to conclude with some information that I have gathered on manuscripts of Ibn Hajar’s al-Badhl al-maʿun fi fawaʾid (some manuscripts read fadaʾil) al-taʿun (‘The granter of aid: On the benefits/merits of the plague’). Note that the title of this text already suggests that the plague had ‘benefits’ or ‘merits’ because it reminded people of the importance of sabr and of the Last Day. I gathered this information in the context of earlier research with the Ghent-based ‘Mamlukisation of the Mamluk Sultanate II’ project (PI Jo Van Steenbergen). This text is quite well attested in manuscript form: the earliest studies of it were undertaken on a manuscript in the Escorial Library (which most likely originated in the Maghreb), Brockelmann mentions four more copies in his Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur, and today several more can be identified. For example, the Egyptian Dar al-Kutub holds no fewer than four manuscripts of the text. One of these is an interesting case of a manuscript becoming a network of various types of text reuse, not only in its body text but also in its paratexts. This manuscript’s main text is followed by appendices containing biographical notices taken from Ibn Khallikan’s Wafayat al-aʿyan, and it is preceded by two folios of various Hadiths (with attributions). A cursory overview suggests that this material is intimately related to the body text, as it provides additional material to evaluate the soundness of the Hadiths quoted by Ibn Hajar al-ʿAsqalani. See my description of the manuscript here.

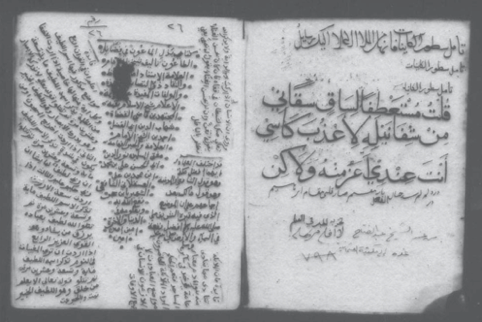

Similarly, a manuscript of the same text from the Damascene Zahiriyya Library (number 62), of which a microfilm scan circulates online, showcases how the very pages of a manuscript could become an arena of scholarly debate: the margins and title page contain various reading notes elaborating on issues raised in the main text.

Figure 3: A scan of the title page of a Zahiriyya Library copy of al-Badhl al-maʿun with a rather extensive amount of annotation.

This kind of material highlights another important caveat to keep in mind when studying a topic such as the plague only through edited texts or through the corpus approach we apply in KITAB. While apps such as the OpenITI NgramReader+ or algorithmic analysis through passim provide valuable data, it is still important to take into account the physical objects through which texts have come down to us if we want to investigate how texts were received and reproduced.

-

Geert-Jan van Gelder, Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 85–6. For another translation and thorough analysis of the poem, see Adam Talib, ‘The Many Lives of Arabic Verse: Ibn Nubatah al-Misri Mourns More than Once’, Journal of Arabic Literature 44 (2013), 257–92. ↩

-

On Ibn Nubata’s elegies for his children, see Thomas Bauer, ‘Communication and Emotion: The Case of Ibn Nubātah’s Kindertotenlieder’, Mamlūk Studies Review 7 (2003), 49–95. ↩

-

On the plague in general, see, amongst others, several contributions by Lawrence I. Conrad, especially ‘Taʿun and Wabaʾ: Conceptions of Plague and Pestilence in Early Islam’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 25, no. 3 (1982), 268–307; Michael Dols, The Black Death in the Middle East (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977); Stuart Borsch, The Black Death in Egypt and England: A Comparative Study (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005); Nükhet Varlik, ‘Between Local and Universal: Translating Knowledge in Early Modern Ottoman Plague Treatises’, in P. Manning and A. Owen, eds, Knowledge in Translation: Global Patterns of Scientific Exchange, 1000–1800 CE (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018), 177–90. ↩

-

The proper way to cite the NgramReader+ is as follows: Maxim Romanov, OpenITI NgramReader+ (Version 2020.1), Zenodo, 24 March 2020, http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3725855. ↩