It is not accidental that a large number of books in the OpenITI corpus belong to one important genre, prophetic Hadith – the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad and accounts of his practice. As a repository of the prophetic tradition (sunna), they are considered an authoritative source of law and moral guidance in Islam. When early Muslim religious scholars sought ‘knowledge’ (ʿilm), they often meant Hadith. In this blog post, I will briefly discuss what Shiʿi Hadith is and provide some preliminary ideas towards reconstructing early Hadith transmission through computational reading.

The main difference between the Shiʿi and Sunni notions of Hadith is that for the Shiʿis the accounts of their imams are equally authoritative compared to those of the Prophet. Shiʿi Muslims generally recognise as authentic the six canonical collections1 of Sunni Islam containing reports about what the Prophet Muhammad said, did or approved, in addition to their own collections.2 However, for a tradition to be considered a legitimate source of law in Shiʿi Islam, its chain of narrators (isnad) has to go back to ʿAli b. Abi Talib (d. 40/661), the fourth caliph and the first Shiʿi imam; his wife Fatima, daughter of the Prophet; or to their descendants. It is primarily for this reason that the collection, transmission and codification of Shiʿi Hadith had its own trajectory and specificities.

Early individual collections of Shiʿi Hadith were first-hand reports from the imams, which were known as usul (origins, primary sources) or simply as kutub (writings, notebooks) to later Hadith scholars. On occasion, the later compilers named their sources, which is useful for modern historians. For example, in the Kitab al-Idah, the first known Ismaʿili Shiʿi compendium of legal Hadith – a vast compilation that surpassed all canonical Hadith collections, Sunni and Shiʿi, in volume but of which only a small portion survives – the famous Fatimid jurist al-Qadi al-Nuʿman (d. 362/974) consistently quoted his written sources in the following manner:

[It is reported] in the Book of al-Halabi, known as the Kitab al-Masaʾil, from Abi ʿAbd Allah Jaʿfar b. Muhammad [al-Sadiq, the fifth Shiʿi imam], that he said: [matn, i.e. the actual report].3

However, this was not the standard practice. Despite the fact that Hadith compilers relied on written sources, they never felt the need to mention them, though they invariably recorded the chains of transmitters. This was largely due to the fact that the authority of oral transmitters usually took precedence over that of a written source. This is one reason only a handful of the early individual collections survive independently. The rest, estimated to amount to between 400 and 1,000 Imami Shiʿi collections from the mid-eighth to the ninth century, have been gradually subsumed into the massive Hadith compilations that appeared from the tenth century onwards. Nevertheless, we know about the existence of these early collections from bibliographical works, such as the Fihrist of al-Shaykh al-Tusi (d. 460/1067), although his information also came mainly from oral sources.4

We need to add at this point that the authenticity of both Sunni and Shiʿi Hadith is predicated on the veracity of their isnads. Most Hadith have a structure consisting of an isnad followed by a matn (textual report) similar to this:

A report from Ahmad, from Muhammad, from Yusuf, from an Egyptian man, who was with ʿAli b. Abi Talib when he said: ‘The Prophet said: [the matn]’.

As discussed in a recent blog post by Ryan Muther, the relative consistency of the structural elements of Hadith, with its standard transmissive terms and established pattern of isnad – matn – isnad, makes Hadith a promising area and an important subject matter for computational reading and text-mining.

Daʿaʾim al-Islam, the Shiʿi Hadith corpus, and the passim algorithm

In this post, I will test the search, navigation and text-mining tools created by the KITAB team which make it possible to extract information from vast corpora such as the OpenITI corpus on a select number of Shiʿi Hadith works. I have chosen the Kitab Daʿaʾim al-Islam (‘The pillars of Islam’), the important compendium of legal Hadith by al-Qadi al-Nuʿman, as an example. I will be mainly dealing with a KITAB visualisation application which visualises alignments between two texts detected by the passim algorithm (which is not yet publicly available).

Even when passim outputs, in the form of textual alignments, might point to text reuse or a direct relationship between two closely aligned texts, the data can also indicate simply that the two texts share common sources. The original sources are often lost, as is the case with primary sources for Shiʿi Hadith, although hundreds of them were in circulation from the eighth century onwards. Let us look at both types of relationship – the one involving common (lost) sources, and the other involving a direct relationship – through the case of the Daʿaʾim al-Islam. We will begin by looking at the relationship formed through drawing on common sources.

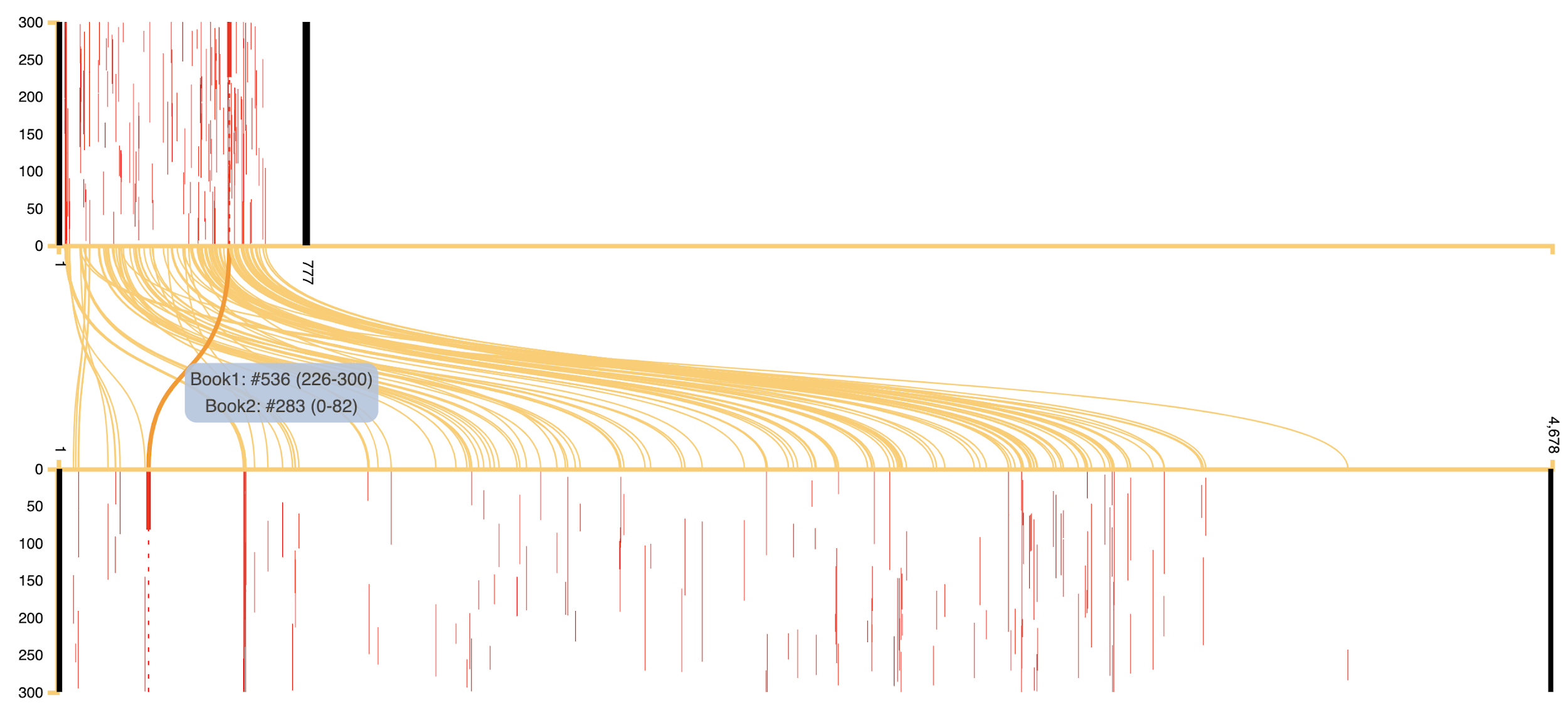

The first example is a comparison between the Daʿaʾim and the Kitab al-Kafi of al-Kulayni (d. 329/941), the first canonical Imami Shiʿi Hadith collection. Both works were compiled roughly around the same time, in Kairouan (modern Tunisia) and Baghdad, respectively, so it is most likely that the authors did not have direct access to each other’s books. However, because both works were drawing on many common Shiʿi sources and early Hadith collections, the algorithmic reading of the texts yields a significant number of alignments. The figure below visualises 152 common passages detected by passim. Here, the width of the red lines indicates the length of the reused text in each of the books. Typically, unless a book has been directly reused, the number of paired alignments will be few and one will not be able to get a quick idea about the nature of the relationship between the texts. This is what happens when we compare the Daʿaʾim with the earliest Hadith collections. However, when we compare it with comprehensive compendia such as the Kafi, we get an instant sense of the structure of the texts.

Figure 1: Top: Daʿaʾim al-Islam; bottom: al-Kafi of al-Kulayni. There are 152 alignments between the two texts. The books are split into 300-word milestones to facilitate running the text reuse algorithm passim. The numbers that appear in the box indicate the milestones within which the alignments occur in each of the two books (here, milestone 536 in book 1 and milestone 283 in book 2). The numbers in parentheses represent the location of the alignment within the milestone.

As illustrated by Figure 1, the Daʿaʾim and al-Kafi are structured similarly. This is to be expected, because Hadith compilations are usually arranged according to common legal topics. Both works are also considered among the most important sources of Shiʿi law, which raises questions about the boundaries between Hadith and fiqh (the Islamic legal tradition) and their mutual influence. Hence, text reuse methods can be a starting point for addressing research questions pertinent to the formation of these traditions. Having seen how the KITAB application provides a ‘bird’s-eye view’ of the two texts, we will now try the ‘deep dive’ approach by diving into the text to find granular details. For information about the usage of Hadith in different legal traditions, individual records can be instantly viewed for comparison and context. For instance, we may want to find out why one pair of alignments between the Daʿaʾim and al-Kafi, highlighted in the above visualisation, does not follow the general pattern (Figure 1, Book 1, at milestone 536). Clicking on the line opens the passage in question in an alignment reader.

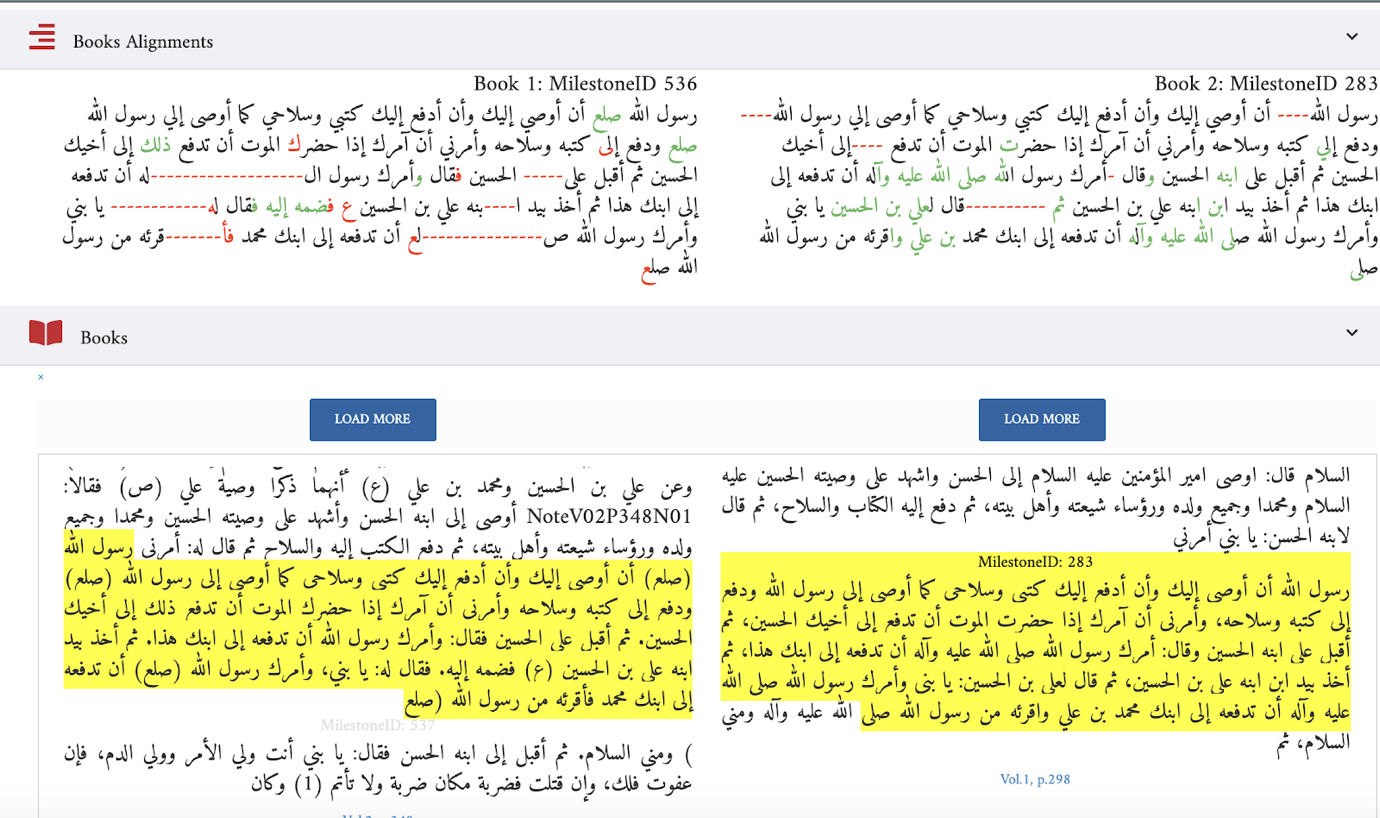

Figure 2: Comparing Hadith in the Daʿaʾim (Book 1) and al-Kafi (Book 2) in an alignment reader to see the context in which the alignment occurs.

The passages above contain a Hadith about ʿAli b. Abi Talib’s will to his sons, in which he is said to have bequeathed his weapons and books to his elder son al-Hasan, whom he also appointed as his successor in the presence of his other sons, family and supporters. Al-Nuʿman uses this tradition to make a juridical point in the Kitab al-Wasaya (‘Book of wills’), whereas al-Kulayni brings it up in the Usul part of his al-Kafi to make a theological argument about the designation of imams, one after another (the doctrine of nass). Same story, different interpretations.

Although they draw on shared sources, the divergences between the Daʿaʾim and other early compilations are expected. First of all, al-Qadi al-Nuʿman’s allegiance to the Fatimids, which makes him the first and the last Ismaʿili Hadith compiler, informed his choices as a compiler. He was also the only major Shiʿi compiler from the Maghreb, whereas all the canonical hadith collections (six Sunni and four Shiʿi) were compiled by natives of Iran and Khurasan. Hence, his sources may have been unknown in the East or deliberately neglected by Eastern compilers because of doctrinal biases, and vice versa. In fact, some early sources quoted by al-Nuʿman were still unknown even to early modern compilers such as Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi (d. 1111/1687), whose enormous compilation, the Bihar al-anwar (‘Oceans of light’), is otherwise exhaustive. Thus, not detecting text reuse is equally informative, and al-Nuʿman’s compilations provide an interesting case for further exploration.

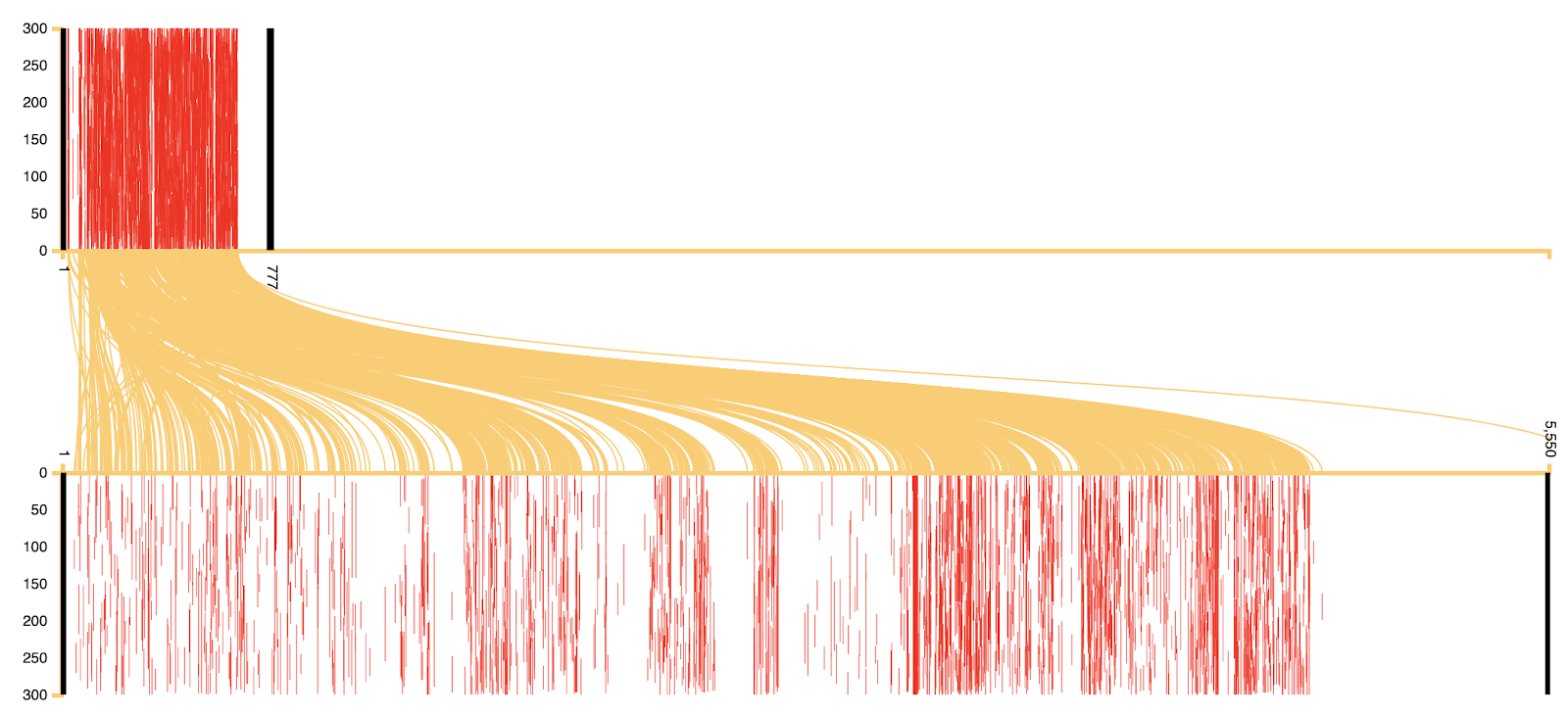

Next we turn to the second type of relationship between texts, namely a relationship of direct reuse. After the fall of the Fatimid Empire, the Daʿaʾim retained its status as the most authoritative legal code among the Tayyibi Ismaʿilis and was mainly preserved by their scholars. It seems to have also been known to most Shiʿi Hadith compilers in later periods. Whereas the earliest Imami Shiʿi scholars did not include al-Nuʿman in their biographical dictionaries, his name and works are gradually mentioned in later works, beginning with Ibn Shahrashub’s (d. 588/1192) Maʿalim al-ʿulamaʾ. He was eventually claimed as an Imami scholar, probably first by Qadi Nur Allah al-Shushtari (d. 1019/1610), according to Poonawala.5 Thus, visual comparison between the Daʿaʾim and major medieval Shiʿi compendia reveals a pattern similar to the one described above, followed even by al-Hurr al-ʿAmili’s (d. 1104/1624) massive Hadith compilation, Tafsil Wasaʾil al-Shiʿa. We see direct quotation from the Daʿaʾim beginning with the largest compilation of the Safavid period, the Bihar al-anwar of al-Majlisi, who also noted the misattribution of the Daʿaʾim to Ibn Babawayh (d. 381/991) and asserted that the real author, al-Qadi Nuʿman, was an Imami scholar. With the next great compilation of legal Hadith, Mirza Husayn Nuri Tabarsi’s (d. 1320/1902) Mustadrak al-Wasaʾil, the Daʿaʾim was fully absorbed into the Shiʿi Hadith corpus (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Top: Daʿaʾim al-Islam; bottom: Mustadrak al-Wasaʾil. Tabarsi’s quotation from the Daʿaʾim is the most extensive among the Shiʿi sources in our corpus (1,920 alignments).

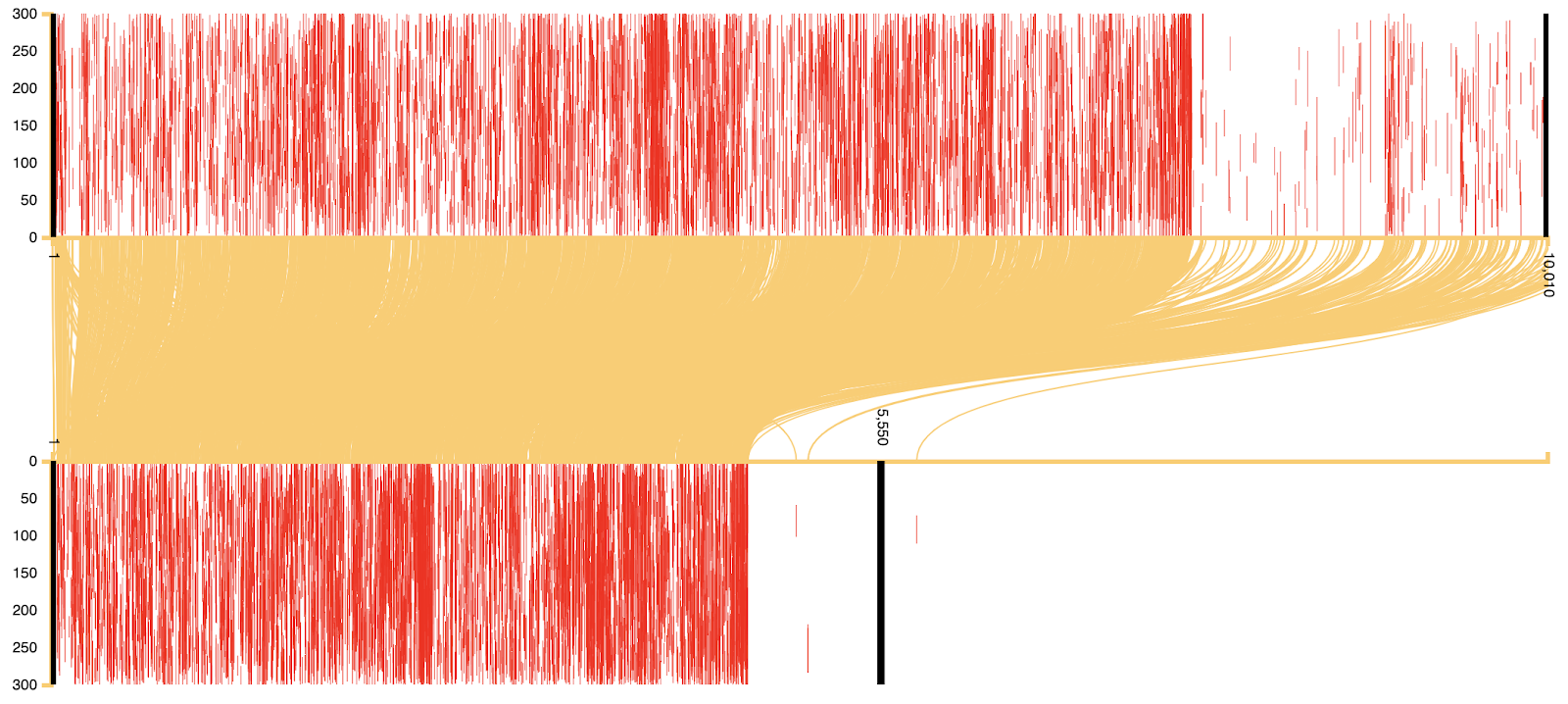

Tabarsi’s Mustadrak (‘Supplement’) to al-Hurr al-ʿAmili’s Wasaʾil al-Shiʿa (Figure 4) is one of the largest and most recent Shiʿi compilations, comprising eighteen volumes. Given that the Daʿaʾim has the biggest number of alignments with the Mustadrak (1,920 records), Tabarsi must have considered the Daʿaʾim a major omission from the work of his predecessor. The overall number of direct quotations from the Daʿaʾim in which the source is cited is 2,580. It should, however, be noted that not all direct quotations are picked up by passim, because not all of them result in significant textual overlap. Paraphrasing and alterations can also influence the output. This nuance should be taken into account when comparing Hadith works.

On the other hand, the Hadith corpus is so vast and its oral and written sources are so numerous that it necessarily leads to various types of transtextualities. In Hadith compilations, both different source texts and variant isnads warranted repeated quotation of the same Hadith. Even when texts were intended as a ‘supplement’ to another work, repetitions could not be avoided, and Tabarsi’s Mustadrak is a good example. Tabarsi, in fact, was conscious of this and included the following disclaimer in his introduction:

If one comes across a Hadith that is also found in the original work [Wasaʿil], quoted from the same book that we have quoted, he should not rush to blame us. This is because the Shaykh [al-ʿAmili] often mentions a Hadith in a chapter with little relevance to that chapter, while it would have been more appropriate to include it in another. Because we did not find a Hadith where it was expected and did not check the other chapter, we may have deemed it an omission and included it [repeatedly]. We found some of these and corrected them, but if some are still there, their presence will not harm, nor should it give a reason for criticism. How true is the saying, ‘The one who compiled has made himself a target.’6

I hope the present post has showcased how digital methods help to solve the ‘information management’ problem described by Tabarsi.

Figure 4: Top: Wasaʾil al-Shiʿa of al-Hurr al-ʿAmili; bottom: Mustadrak al-Wasaʾil, Tabarsi’s supplement.

As a final observation, computational methods facilitate instantaneous reading and analysis of thousands of traditions and chains of transmissions. Perhaps a few exceptional individuals are able to combine the kind of bird’s-eye view and scrutiny offered by the modern digital toolbox, but it is inconceivable that they will be able to do so with the same precision or pace. These new computational tools can not only help rethink the standard questions about knowledge transmission but also explore the complex ways in which cultural memory was formed, transmitted and perpetuated. Digital Humanities, while itself a recent and likely a temporary shorthand to refer to a set of digital methods and toolboxes, may help us challenge an array of neologisms and modern constructions in the field of Islamic studies, and return us to closer access to source texts, thus allowing the texts to speak for themselves. Ultimately and ironically, these methods will help us recognise the merits of the so-called traditional Muslim sources by reconstructing the history of knowledge production and transmission as it unfolded organically.

References and further reading

Ahmed, Shahab, Ahmad Kazemi-Moussavi and Ismail K. Poonawala, ‘Hadith i–iii’, in Encyclopaedia Iranica, xi/4, available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/hadith-index (accessed 1 May 2020). For a general introduction to Hadith and Hadith studies, with informative sections on Shiʿi and Ismaʿili Hadith.

Daftary, Farhad, and Gurdofarid Miskinzoda, eds, The Study of Shiʿi Islam: History, Theology and Law (London: I. B. Tauris, 2016).

Gleave, Robert, ‘Between Hadith and Fiqh: The “Canonical” Imami Collections of Akhbar’, Islamic Law and Society 8, no. 3 (2001), 350–82.

Kohlberg, Etan, ‘Shiʿi Hadith’, inn A. F. L. Beeston, ed., The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature, i: Arabic Literature until the End of the Umayyad Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 299–307.

Kohlberg, Etan, ‘Al-Usul al-arbaʿumiʾa’, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 10 (1987), 128–65.

Madelung, Wilferd, ‘The Sources of Ismaʿili Law’, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 35 (1976), 29–40.

Modarressi, Hossein, Tradition and Survival: A Bibliographic Survey of Early Shi’ite Literature (Oxford: Oneworld, 2003).

Poonawala, Ismail K., ‘The Chronology of al-Qadi l-Nuʿman’s Works’, Arabica 65 (2018), 84–162.

Al-Qadi al-Nuʿman, Abu Hanifa b. Muhammad, Daʿaʾim al-Islam wa-dhikr al-halal wa-l-haram wa-l-qadaya wa-l-ahkam, ed. Asaf A. A. Fyzee, 2 vols (Cairo: Dar al-Maʿarif, 1951–60); English trans. as The Pillars of Islam, trans. Ismail K. H. Poonawala, 2 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002–4).

Al-Qadi al-Nuʿman, Kitab al-Idah, ed. Muhammad Kazim Rahmati (Qum: Markaz-i Tahqiqat-i Dar al-Hadith, 2003).

Tabarsi, Mirza Husayn al-Nuri, Mustadrak al-Wasaʾil wa-mustanbat al-masaʾil, ed. Muʾassasat Al al-Bayt, 3rd ed., 18 vols (Beirut: Muʾassasat Al al-Bayt li-Ihyaʾ al-Turath, 1991).

-

The six canonical Sunni Hadith collections, known as ‘The Authentic Six’: Jamiʿ al-sahih of Muhammad b. Ismaʿil al-Bukhari (d. 256/870), Jamiʿ al-sahih of Muslim b. Hajjaj al-Naysaburi (d. 261/874), Sunan of Abu Dawud al-Sijistani (d. 275/888), Sunan of Muhammad b. ʿIsa al-Tirmidhi (d. 279/892), Sunan of Ibn Maja al-Qazwini (d. 275/886) and Sunan of Ahmad b. Shuʿayb al-Nasaʾi (d. 302/915). ↩

-

Four Twelver Shiʿi canonical collections, known as ‘The Four Books’: al-Kafi fi ʿilm al-din of Muhammad b. Yaʿqub al-Kulayni (d. 329/941); Man la yahduruhu al-faqih of Ibn Babawayh, al-Shaykh al-Saduq (d. 381/991); and Tahdhib al-ahkam and al-Istibsar fi ma ikhtalafa min al-akhbar of Muhammad b. Hasan, al-Shaykh al-Tusi (d. 460/1067). ↩

-

Al-Qadi al-Nuʿman, Kitab al-Idah, ed. Muhammad Kazim Rahmati (Qum: Markaz-i Tahqiqat-i Dar al-Hadith, 2003), 207. ↩

-

Etan Kohlberg, ‘Al-Usul al-arbaʿumiʾa’, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 10 (1987), 128–65. ↩

-

Ismail Poonawala, ‘The Chronology of al-Qadi l-Nuʿman’s Works’, Arabica 65 (2018), 84–162, 88. ↩

-

Mirza Husayn al-Nuri Tabarsi, Mustadrak al-Wasaʾil wa-mustanbat al-masaʾil, ed. Muʾassasat Al al-Bayt, 3rd ed., 18 vols (Beirut: Muʾassasat Al al-Bayt li-Ihyaʾ al-Turath, 1991), i, 62. ↩