The digital revolution is arriving rather late to Middle Eastern studies, but it is coming fast.

Now, we can see the written tradition at a distance with KITAB’s first data set. Spoiler: it is hugely intertextual.

There are important caveats: we need to build a more representative corpus; the text reuse software that we use needs further optimisation. Still, I would propose that we can already learn a lot.

Let me describe this data set, and some of what we can see at first glance. I base my comments on statistics that the KITAB team assembled this summer and which we are studying with Microsoft Power BI (a suite of analytics tools).

Bear with me, as what follows will necessarily be a bit granular.

We ran passim – text reuse software developed by David Smith – on the entirety of KITAB’s corpus, comparing the words of each of 4,260 books to the words of every other text (~18 million book comparisons). This process – including a 5-gram ‘shingling’ method – involved a few simple steps repeated trillions of times as passim searched for, and aligned, common passages. Every time it found a common passage of at least 10 and up to 300 words, it created a record of the match within a file dedicated to the relationship between the two books (so, potentially ~18 million files containing billions of records).

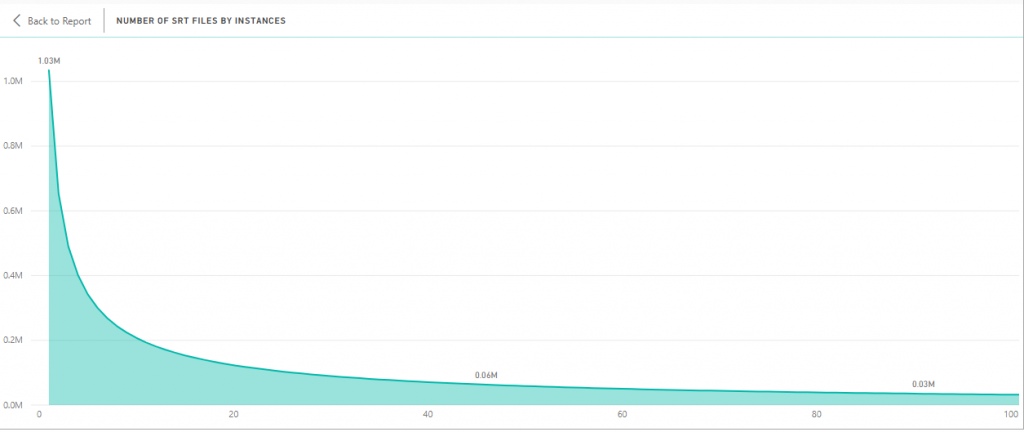

In total, passim generated 1.03 million such files containing ~23 billion records (or instances of reuse) made up of 983 billion words. This means that 5.7% of the time, in comparing any book in the corpus to any other book in the corpus, it found at least one instance of common wording. This might seem remarkable. These books were comprehensively paired – the equivalent of comparing Wuthering Heights and King Lear – and 5.7% of the time passim found a common passage between such pairs. But, as with English greats, there are accidents of language, especially given the frequency of many Arabic names, words and phrases.

The above comparison represents an insignificant record of reuse. On the left is a passage from the Musnad of Ahmad b. Hanbal (d. 241/855) and on the right a passage from the Kitab al-Tawhid by Ibn Babawayh (d. 381/991–2). Passim detected this single instance of reuse between the two works, even though the Musnad totals ~1.7 million words and the Kitab al-Tawhid 140,000.

When passim recorded only one such instance of reuse between two books, the substance of the reuse is virtually always of no interest and reveals no meaningful relationship between the books (e.g. no direct use or major common source). Similarly, two or three records of reuse are (most) often matters of pure accident. Of the ~1 million files, approximately 600,000 contain only three or fewer records.

The graph above shows how much the data is dominated by files documenting, frankly, meaningless relationships. The y-axis tracks the number of files and the x-axis the number of records for a pair of compared books (specifically, 1 = at least one record in a file, 2 = at least two records, and so on). The number of files drops steeply as the number of records increases. There were ~18 million possible matches, and ~1 million times books match with at least one record. By contrast, the far right of the graph shows that there were about ~32,000 files with at least 100 matches.

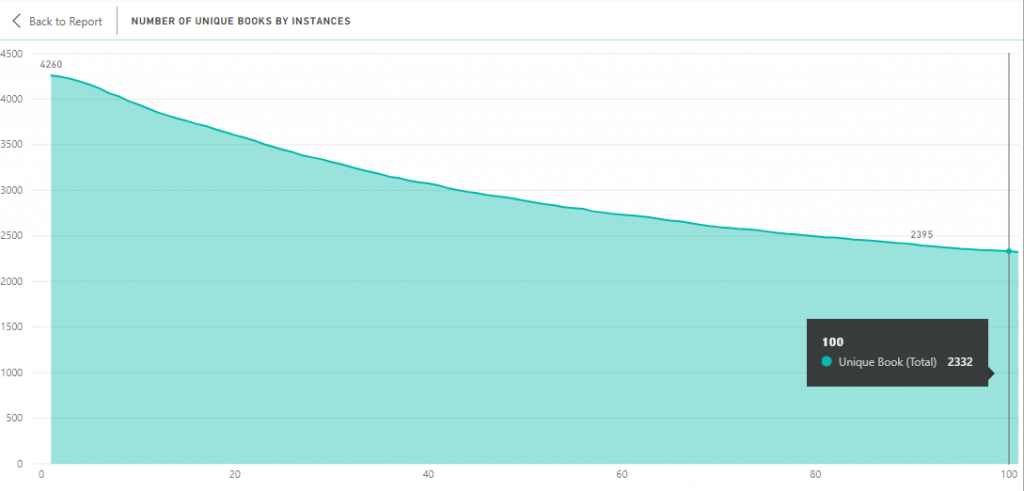

We do not know yet at what point in counting such instances we can assume two texts to have a historically meaningful relationship – and there was likely no specific tipping point at, say, four or five matches. But what is much more interesting is that most books in our corpus do have a significant relationship with at least one other book, and a very large number of them have a very substantial one. In other words, it is uncommon to find a book that is independent of all others. This is another way of slicing the same data.

The above graph shows that many of our works have much in common with other works. The y-axis shows the number of books and the x-axis the number of records of reuse (specifically, 1 = at least one record in a file, 2 = at least two records, and so on). Of the 4,260 books analysed, 3,606 – or 85% – have at least twenty passages in common with another book. As you can see at the far right of the graph, of the 4,260 books, just over half (2,332) contain at least 100 records of passages shared with another book.

So, although many relationships are meaningless, we do have many meaningful ones. And most books are meaningfully linked to other books.

What is perhaps even more interesting, and ready for our analysis now, is the outliers – the cases in which the reuse is enormous. Filtering our data shows the following, for example:

-

For 25% of our 4,260 books, more than 50% of the book matches at least one other book in the corpus (reckoned by word count); similarly, for 18% of our corpus, or 757 books, our approach identified 1,000 or more instances of text reuse with another book.

-

Works typically classified as pertaining to Hadith are massively intertextual. For example, despite the example of meaningless reuse cited above, the Musnad of Ahmad b. Hanbal shares hundreds of thousands of words with other individual books.

-

Many authors substantially repeat themselves.

This high degree of reuse should make us reconsider many assumptions we hold about the textual tradition as a whole – including, for example, how the people who produced such works conceived of what they were doing.

In the coming weeks and months, stay tuned as we provide more overviews and details from this data set and other sets that we are working on now.