Some might know the 1945 Buddy Kaye and Ted Mossman song Till the End of Time, made famous by Perry Como. The beginning of the lyrics run like this:

Till the end of time

Long as stars are in the blue

Long as there’s a spring, a bird to sing

I’ll go on loving you

Till the end of time

Long as roses bloom in May

My love for you will grow deeper

With every passing day

Strikingly similar expressions of love are at work in the historical Druze religious poetry which I have been transcribing over the past years for an ongoing side project of mine. As always happens when we spend more than just a fleeting moment with something – a methodologically important point – patterns begin to emerge, and characteristic elements start to appear over and over again.

One such characteristic element in Druze religious poems is grammatical structures that express the notion of ‘as long as,’ and which are formed of the Arabic conjunction mā plus a perfect form such as mā rannama l-ṭayr ‘as long as birds sing,’ mā halla hilāl wa-bāna ‘as long as the crescent moon will show and appear,’ or mā nāḥa qumrī ʿalā l-aghṣān ‘as long as doves will mourn on branches.’ (A non-exhaustive inventory of the instances found in the poems I have transcribed can be found here.)

In light of its linguistic function of expressing perpetuity and duration, this usage of mā normally is referred to as mā al-daymūma in Arabic grammar (see W. M. Wright, vol. 1, p. 294). This function has occasionally been explained by pre-modern authors, for example, by Ibn Juzayy (d. 741 AH/1340 CE) in his Tashīl li-ʿulūm al-tanzīl (vol. 1, p. 406) (‘yakūn ʿibāra ʿan al-taʾbīd ka-qawl al-ʿArab mā lāḥa kawkab wa-mā nāḥa al-ḥamām wa-shibh dhālika mimmā yuqṣad bihi l-dawām’), ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Thaʿālibī (d. 873 AD/1468 CE) in his Jawāhir al-ḥisān (vol. 3, p. 302), or Nūr al-dīn al-Ḥalabī (d. 1044 AD/1635 CE) in his Sīra al-ḥalabiyya (vol. 1, p. 24) (‘al-murād min dhālika l-abad’). These structures occur in Druze poetry with a great variety of images (see below).

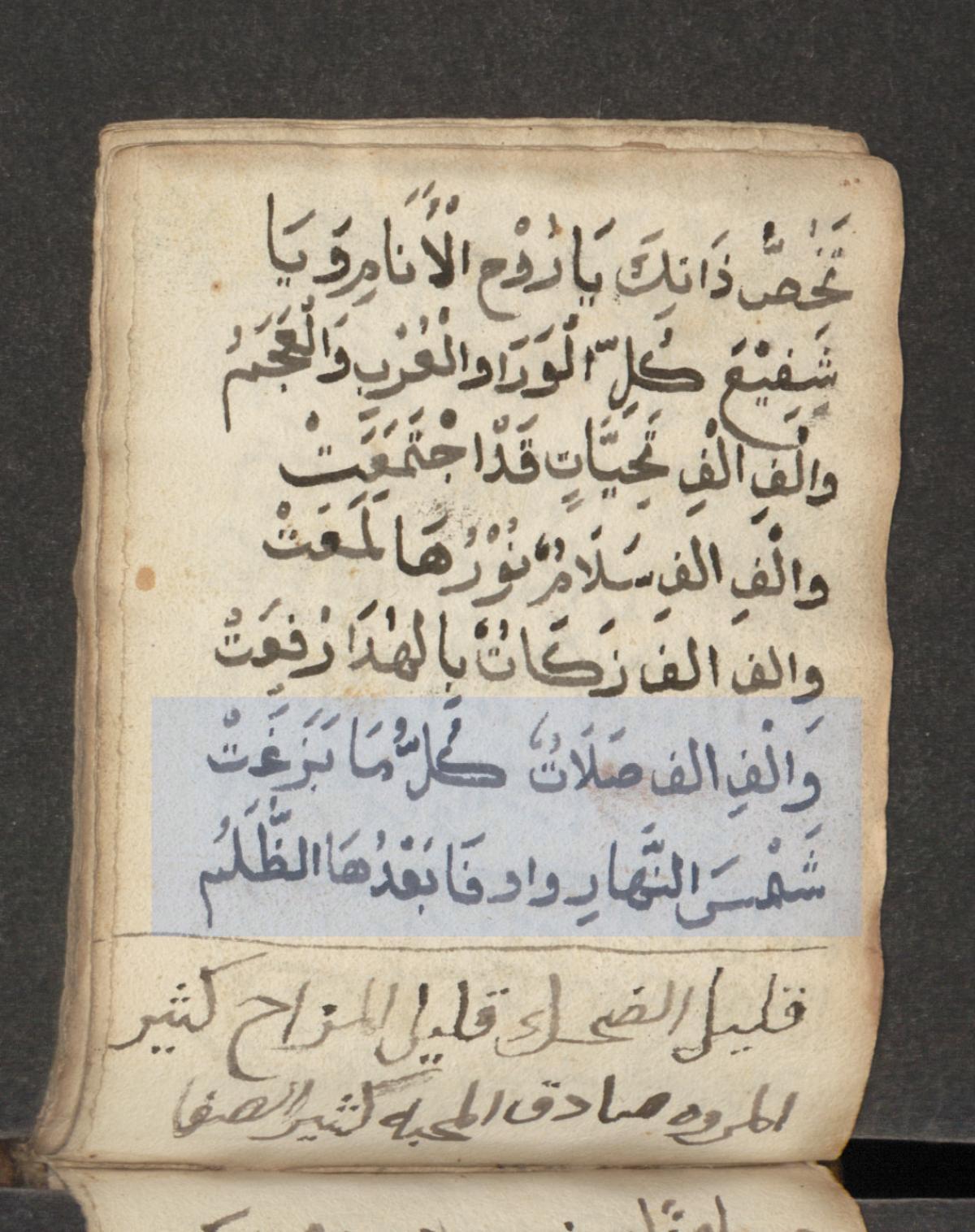

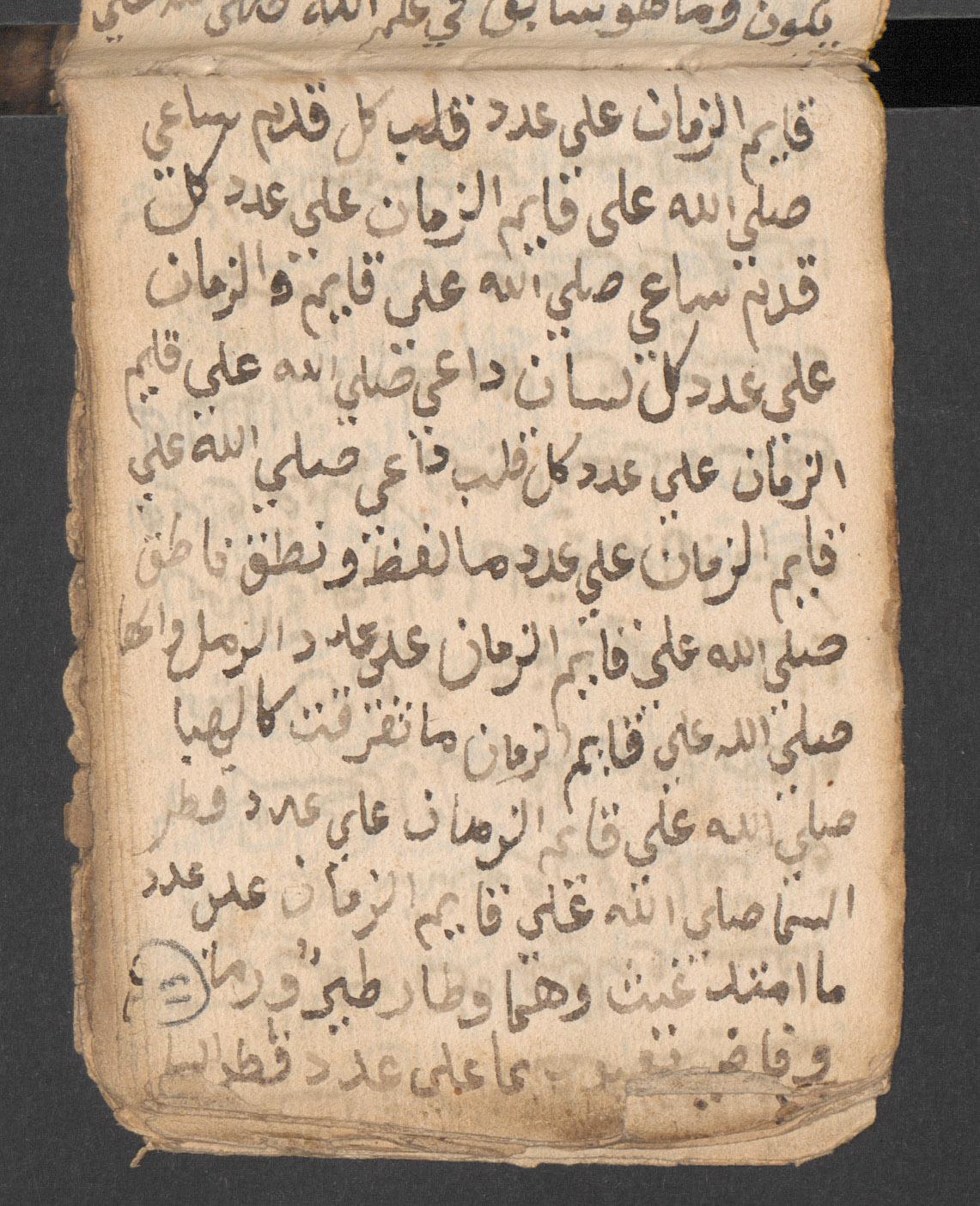

Druze religious poems contain other grammatical structures with analogous functions and in similar positions expressing the notions of ‘whenever’ and ‘as often as,’ most notably kullamā plus a perfect form such as kullamā habbat al-ṣabā ‘whenever the north wind blows’ as well as structures built around the lexeme ʿadad such as ʿadad mā ‘as often as’/’in such numbers as there are’ or ʿalā ʿadad ‘as often as.’ For example, ʿadad mā fī l-buḥūr amwāj ‘in such numbers as there are waves in the seas.’ Last, but not least, there are a few instances where the lexeme madā is used such as in madā l-zamān mā qad dharra shāriq ‘for as long as time itself will last, for as long as the sun will rise’.

In Druze religious poetry, such phrases are extremely common and characteristically occur in the context of prayers and in sections of devotion and praise, and it readily makes sense that, regardless of whether the particular instance involves the notion of ‘as long as,’ ‘whenever,’ or ‘as often as,’ such phrases produce the effect of doubling down in terms of devotion. In fact, such phrases consistently function as a form of emphatically wishing entities of the Druze religious system, and most notably the five Druze luminaries or ḥudūd (sg. ḥadd), a term which in Druze contexts refers both to a hierarchy of cosmic principles and to the historical figures as which they have taken human form at the time of the 11th century CE Druze mission, the best and of expressing one’s lasting loyalty and love for them; one’s steadfast devotion and the intensity and sincerity of it. Reflecting this devotional context, they often occur in combination with optative perfect forms such as ṣallā ‘may the good Lord bless’ such as in ṣallā ʿalayhi llāh mā ṭāra ṭāʾir ‘may the good Lord bless him for as long as birds will fly.’ Their occurrence in devotional sections also explains why they mostly occur towards the end of poems where such devotional sections tend to be found.

To pick a random example, one poem by Druze poet ʿAlī Fāris (d. 1166–1167 AH/1753 CE) ends with the following lines which ask for eternal blessing of the five ḥudūd and others (in Druze contexts, lexemes which refer to the Prophet Muḥammad in Muslim contexts such as al-nabī or al-nabī al-mukhtār normally refer to Ḥamza b. ʿAlī or the ‘Intellect’) :

ونختم بحمد الله حمدا بدآئم

مع الشكر للمختار خير العوالم

وأصحابه والآل أهل الكرآئم

عليهم صلاة الله ما الغيث قد همر

عليهم صلاة الله ما لاح بارق

وما بزغت شمس وما فاه ناطق

وما ترجمت لسن وما الطرف رامق

وما قد هجس فكر وما كوكب زهر

Said effect of ‘doubling down’ is well illustrated by the mā-phrases making up the last five lines, insofar as they express the hope that God may bless the five ḥudūd and others for ‘as long as rain will pour down, as long as lightnings will flare up in clouds, as long as the sun will rise, as long as mouths will utter words, as long as tongues will praise, as long as eyes will look, as long as thoughts will occur to minds, as long as stars will shine.’ Thus, not unlike the Kaye and Mossman song, Druze religious poetry, over and over again, expresses loyalty, depth, and lastingness of devotion and love by pinning them onto phenomena in the natural world such as singing birds, shining stars, blooming flowers, blowing wind, scents, and so forth.

Grammatical Structures Expressing Perpetuity in Other Contexts

If such mā-phrases are extremely common in Druze religious poetry, they are not unique to it. As is well known and can further be corroborated by a mining of the OpenITI/KITAB corpus, such phrases occur in non-Druze Arabic texts of various kinds, including a Qurʾānic verse (see Q 11:108). Unsurprisingly, poetic anthologies such as ʿImād al-dīn al-Iṣfahānī’s (d. 597 AH/1201 CE) Kharīdat al-qaṣr, Ibn Shaʿʿār al-Mawṣilī’s (d. 654 AH/1256 CE) Qalāʾid, or Ibn Aydamir’s (d. 710 AH/1310 CE) Durr al-farīd are particularly rich sources for such phrases. Even a preliminary and non-exhaustive search of our OpenITI/KITAB corpus corroborates not only the wide variety of images contained in relevant phrases but also their occurrence in the same devotional and promissory contexts in which they also occur in Druze texts. Over and over again, people use such phrases to express the sincerity and profoundness of feelings such as love (uḥibbuka mā ghannat bi-wādin ḥamāma ‘I will love you as long doves sing in valleys’) or grief (sa-abkīk mā lāḥa najm ‘I will cry over you as long as stars shine in the night’; sa-abkīka mā nāḥat ḥamāmatu aykatin wa-mā khḍarra fī dawḥi l-riyāḍi qaḍīb ‘I will cry over you as long as doves cry in the thicket and as long as branches green on the trees of the gardens’). Over and over again, people use them to vow that their feelings will last forever.

It is not a coincidence that we find relevant phrases precisely in texts that epitomise the expression of eternal love such as the diwan of Qays b. Mulawwaḥ (‘Majnūn’). For example, one might highlight the following verses taken from the latter which are nothing but one extended promise and vow not to forget his beloved Laylā. More or less the entire passage consists of such mā-phrases (p. 34):

فو الله ما أنساك ما هبت الصبا / وما ناحت الأطيار في وضح الفجر

وما نطقت بالليل سارية القطا / وما صدحت في الصبح غادية الكدر

وما لاح نجم في السماء وما بكت / مطوقة شجوا على فنن السدر

وما طلعت شمس لدى كل شارق / وما هطلت عين على واضح النحر

وما اغطوطش الغربيب واسود لونه/ وما مر طول الدهر ذكرك في صدري

وما حملت أنثى وما خب ذعلب/ وما طفح الآذي في لجج البحر

وما زحفت تحت الرحال بركبها / قلاص تؤم البيت في البلد القفر

فلا تحسبي يا ليل أني نسيتكم / وأن لست مني حيث كنت على ذكر

أيبكي الحمام الورق من فقد إلفه / وتسلو وما لي عن أليفي من صبر

فأقسم لا أنساك ما ذر شارق / وما خب آل في معلمة فقر

ألا ليت شعري هل أبيتن ليلة / أناجيكم حتى أرى غرة الفجر

لقد حملت أيدي الزمان مطيتي / على مركب مستعطل الناب والظفر

The devotional leaning of these phrases also is corroborated by their occurrence in poems that mourn the death of beloved and venerated figures. Illustrative examples of this are found in several of the marāthī on Ibn Taymiyya (d. 728 AH/1328 CE) adduced by Ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī (d. 744 AH/1343 CE) at the end of his ʿUqūd al-durriyya. Considering the promissory function of such phrases, it furthermore makes sense that they occasionally occur in the context of oaths which are a form of promise. For an example, see the Sīra al-Ḥalabiyya (vol. 1, pp. 23–24): ‘In Thy name, oh God, this is the assistance and support Banū Hāshim and the men of ʿAmr b. Rabīʿa of Khuzāʿa have committed by oath to give to each other as long as seaweed is wetted by the sea; as long as the sun rises over mount Thabīr; as long as camels set out into the desert; as long as mounts Abū Qubays and Qayqaʿān are standing; and as long as people visit Mecca.’

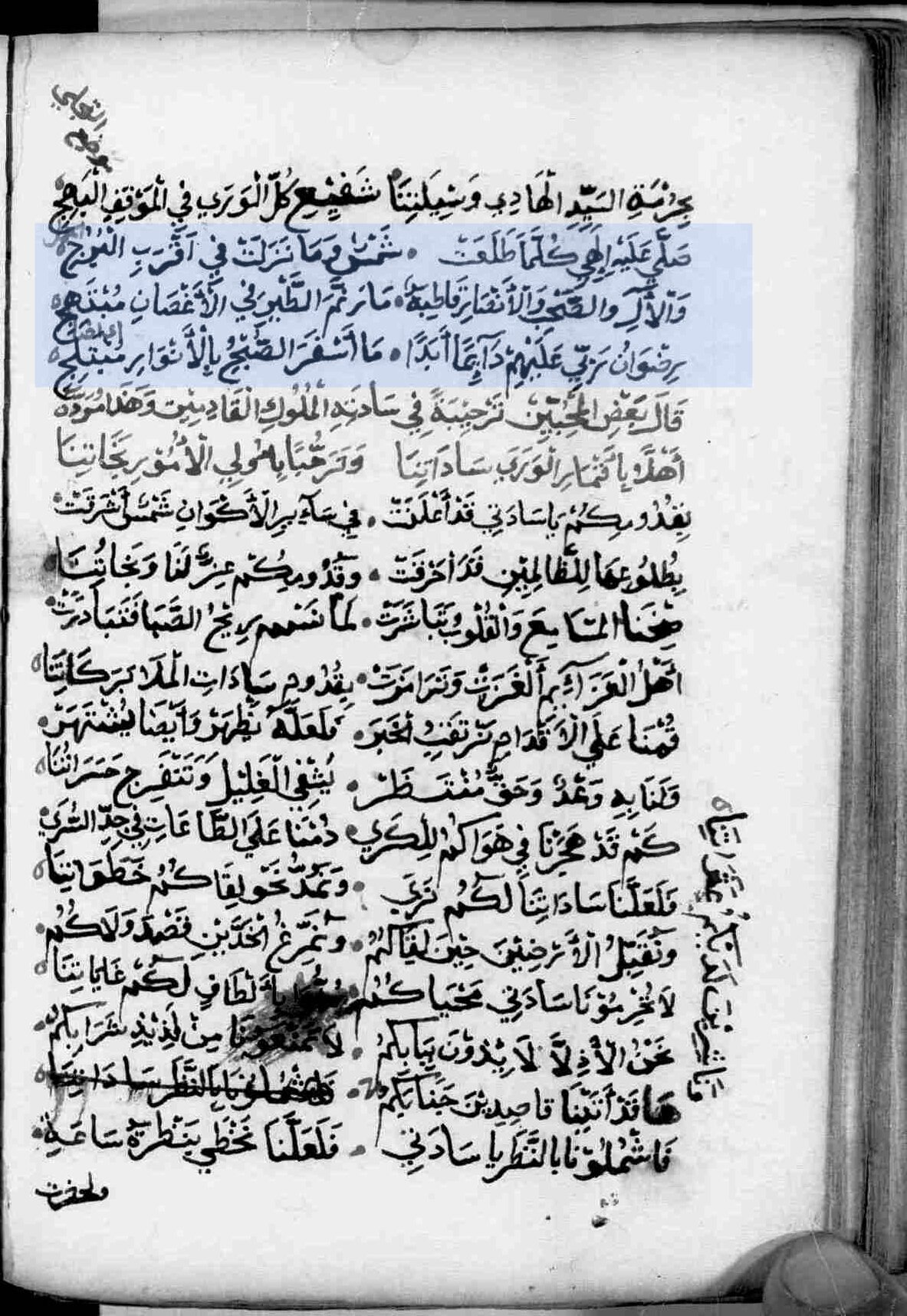

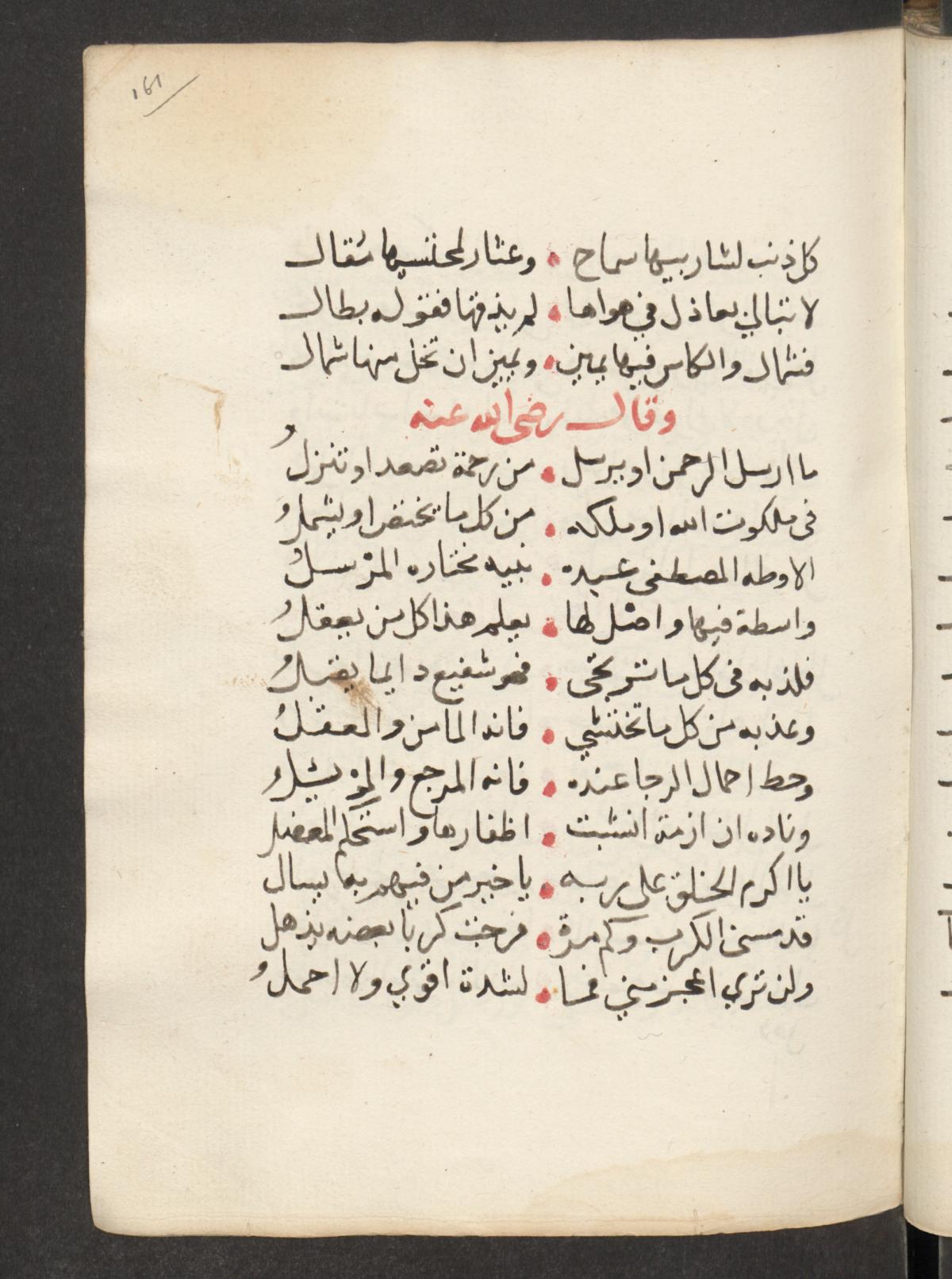

Likewise, the devotional usage of the other grammatical structures referred [to further above that involve kullamā, ʿadad mā, ʿalā ʿadad or similar are not unique to Druze poetry. (See, for example, al-Jazūlī’s (d. 870 AH/1465 CE) Dalāʾil al-khayrāt, a most fascinating and rich text in this regard, or Sayyid b. Ṭāwūs’s (d. 664 AH/1266 CE) Durūʿ. Thus, Druze religious poems simply take up a linguistic element common in the wider cultural and linguistic context to which they belong; they use the same kind of phrases to express the same kind of feelings.

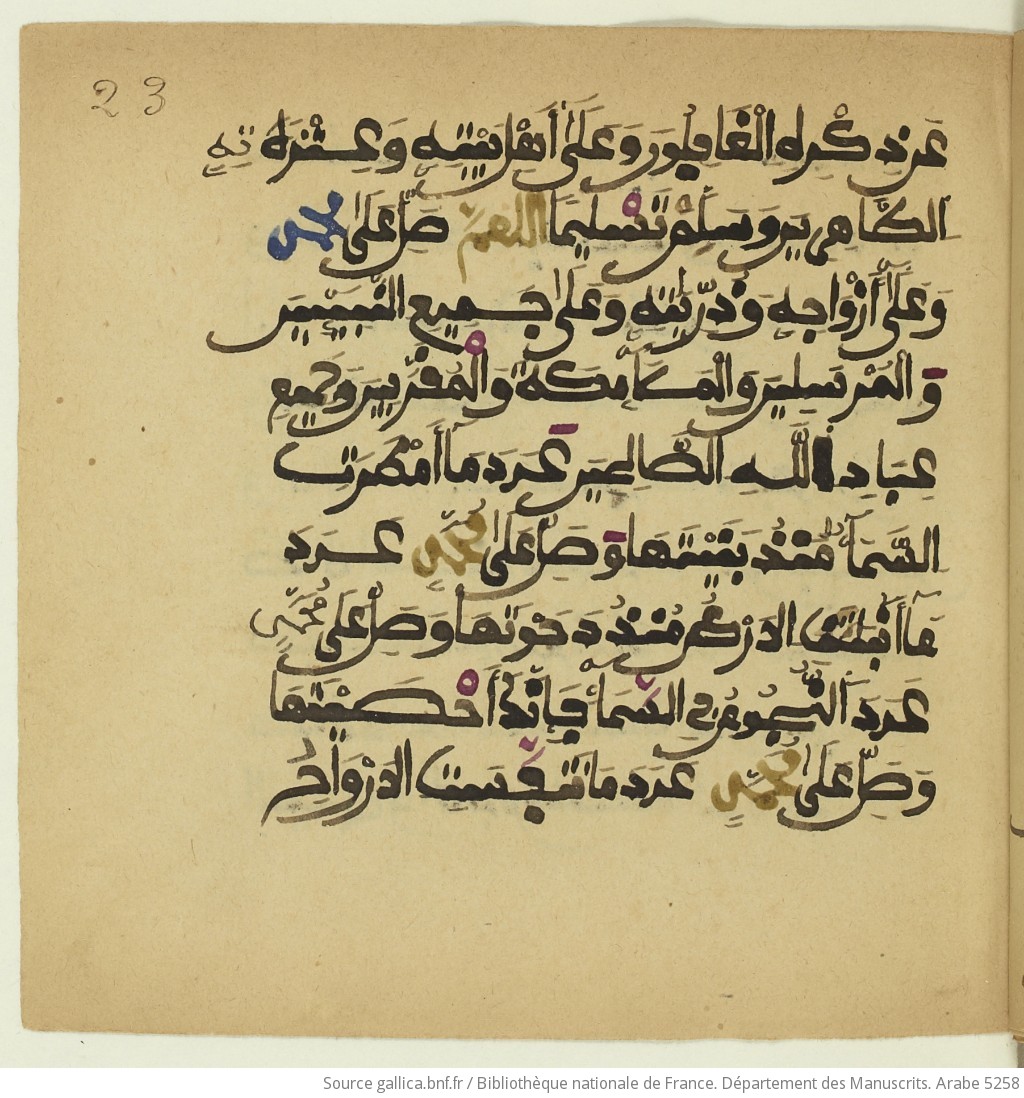

BnF Arabe no. 5258, 23r (from al-Jazūlī’s Dalāʾil al-khayrāt)

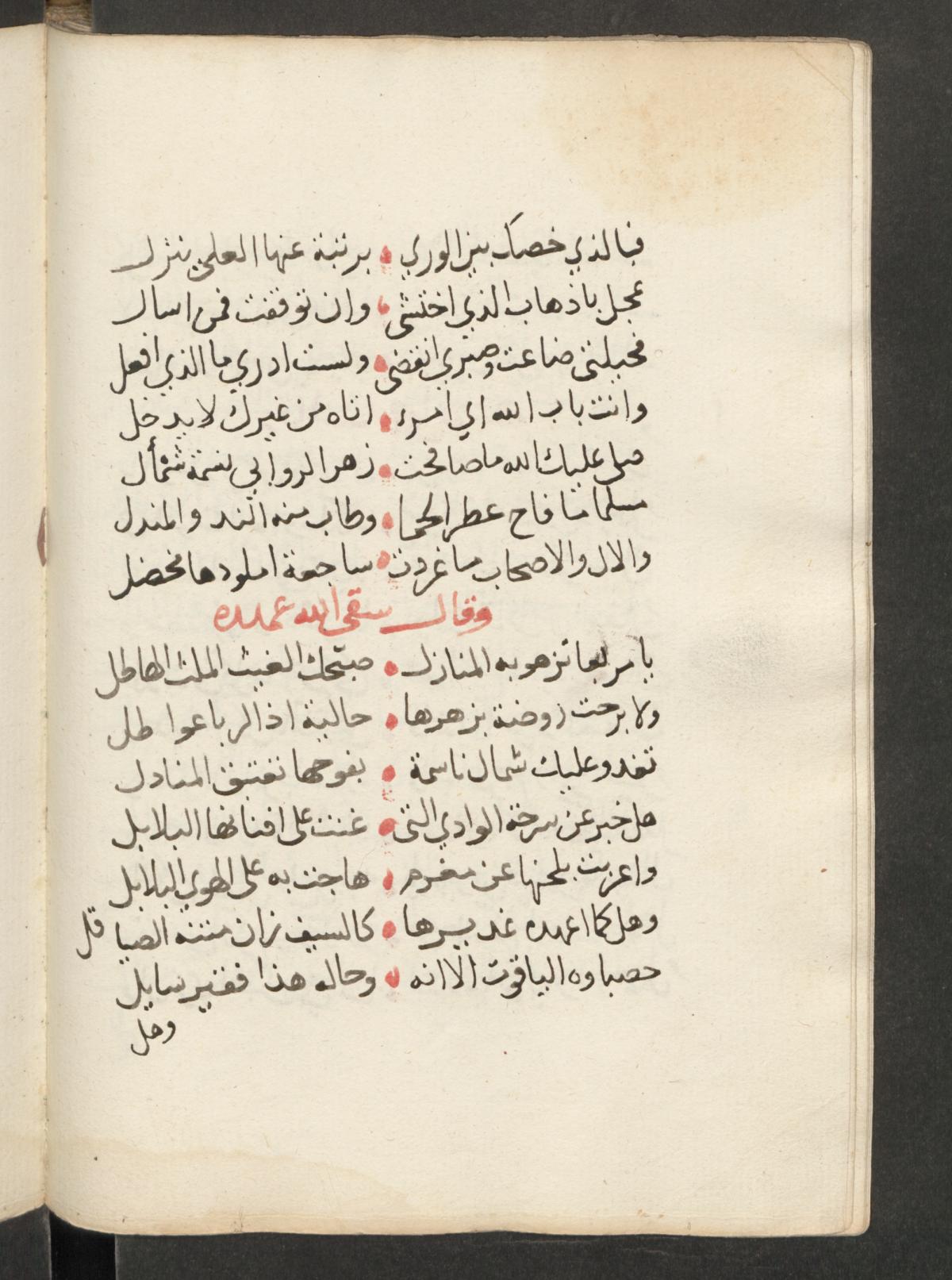

If such phrases are woven into the fabric of Druze religious poems over and over again, it furthermore is important to bear in mind that not every poem found in Druze manuscript sources necessarily is a ‘Druze’ poem. Like everybody else, Druze passed on and jotted down pieces they liked and that meant something to them. An example of this is found in a Druze composite manuscript held by the Spanish National Library. It contains the following verses:

يا أكرم الخلق على ربّه

وخير من فيهم به يسأل

قد مسّني الكرب وكم مرّة

فرجت كربا بعضه يذهل

فبالذي خصّك بين الورى

برتبة عنها لعلا ينزل

عجّل بإذهاب الذي أشتكي

فإن توقّفت فمن أسأل

فحيلتي ضاقت وصبري انقضى

ولست أدري ما الذي أفعل

ولم تر أعجز منّي فما

لشدّة أقوى ولا أحمل

فأنت باب الله أي امرء

أتاه من غيرك لا يدخل

صلى عليك الله ما صافحت

زهر الروابي نسمة شمأل

مسلما ما فاح عطر الربا

وطاب منه الند والمندل

والآل والأصحاب ما غرّدت

ساجعة أملودها مخضل

Towards the end, we find a number of such devotional mā-phrases as described further above: ‘may the good Lord bless you as long as a breeze of north wind blows over the flowers blooming on the hills’ (mā ṣāfaḥat zahr al-rawābī nasamat shamʾal), ‘as long as the hills give off their scent’ (mā fāḥa ʿiṭr al-rubā), and so forth. The verses feel thoroughly Druze. However, with minute differences, they also occur in a poem found in Shams al-dīn al-Bakrī’s (d. 994 AH/1585–1586 CE) Tarjumān al-asrār:

While it is unclear how these verses ended up in the particular manuscript, they certainly do fit into a Druze devotional context.

Pinning Love and Devotion on Phenomena of the Natural World

As can be gleaned from both the Druze and the non-Druze examples, people have come up with a startling number of such phrases. Indeed, based on the limited number of grammatical structures outlined further above, unlimited numbers of these phrases can be formed.

Importantly, while some of these phrases may be leaning more towards abstraction, most of them are resolutely rooted in people’s observations and sensorial experience of their world. Over and over again, we see them refer to bodily experiences and the sensory perception of scents, the falling night, the rising sun, singing birds, shining stars, flaring lightning, rain, breaking waves, the blowing wind, crowing cocks, flowing tears, and so forth. In a sense, a real attention to the natural world shines through these phrases, and there can be no doubt that many of them produce the effect they do because they evoke memories grounded in our bodies and make a connection with what the people who hear and read them have experienced. The images they contain are something everybody can relate to as we have felt such things, seen them, smelled them, and so forth. Take examples such as ‘as long as clouds will pour down in the middle of the night, with lightnings flaring up in the darkness’ (mā haṭalat fī junḥ layl ghamāma bi-khafāq barq fi l-dujna lāmiʿ) or ‘as long as the hills are giving off theirs scents’ (mā fāḥa ʿiṭr al-rubā). Phrases expressing the notion of ‘as often as’ (etc.) betray a similar attention for the world one inhabits as may be illustrated by formulations referring to the ‘number of hairs in a goat’s fur’, the ‘waves in the sea,’ or the ‘stars in the night sky’.

As has been said, in Druze poetry and beyond, these phrases are characteristically used to express the profoundness and totality of someone’s love and loyalty. While such sentiments could be expressed in many other ways, associating them with phenomena that simply form part of the world and are perceived to be there as long as the world lasts surely is an effective way of conveying them. The birds will keep singing and the stars will keep shining, no matter what. Not least, these phenomena continue long after individual human lives have ceased. Grounding the notion of perpetuity in this way makes it more tangible and ‘real’.

No doubt, many of these phrases are stock phrases. But as such they can still make an impression on people and be meaningful to those who use them. It perhaps is not entirely coincidental that lyrics pertaining to a US-American song from the mid 1940s and Arabic verses sometimes hundreds of years older convey feelings in a strikingly similar way.

Repetition That Does Not Get Boring

In Druze poems, such phrases occur so frequently that one can anticipate them, a form of repetition which makes them part of a larger and stable structure of devotion. Whoever spends some time with Druze devotional texts, inevitably begins to be drawn into this structure and, over time, starts to feel at home in it. The fascinating part about this form of repetition is that it does not get boring. On the contrary, especially in the context of devotion and love, repetition is much more than the repeated occurrence of an identical string of characters. Repetition is a form of belonging and being ‘at home’; of being part of a social group; of sharing their hopes, beliefs, feelings, and memories; of anticipating what they anticipate, and so forth.

Leading beyond the scope of this blog, the devotional structure of historical Druze poetry encompasses other repetitive elements that are more specifically Druze in terms of content. The truly fascinating part about these poems is that they manage to transform such more specific theological assertions into devotional literature.

Bibliography

W. M. Wright, A Grammar of the Arabic Language (Cambridge: University Press, 1896).

Nūr al-dīn al-Ḥalabī, al-Sīra al-ḥalabiyya, ed. ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad al-Khalīlī (Beirut: Dār al-kutub al-ʿilmiyya, 2013).

Ibn Juzayy, Tashīl li-ʿulūm al-tanzīl, ed. Muḥammad Sālim Hāshim (Beirut: Dār al-kutub al-ʿilmiyya, 1995).

Qays b. Mulawwaḥ, Dīwān Qays b. Mulawwaḥ/Majnūn Laylā, ed. Yusrī ʿAbd al-Ghanī (Beirut: Dār al-kutub al-ʿilmiyya, 1999).

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Thaʿālibī, al-Jawāhir al-ḥisān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān, ed. ʿAlī Muḥammad Muʿawwaḍ and ʿĀdil Aḥmad ʿAbd al-Mawjūd (Beirut: Dār Iḥyāʾ al-turāth al-ʿarabī and Muʾassasat al-taʾrīkh al-ʿarabī, 1997).