With currently more than 7,000 titles, collected from a number of huge digital Arabic libraries (al-Jamiʿ al-Kabir, al-Maktaba al-Shamila, Shia Online, etc.), the OpenITI corpus is recognised as one of the most comprehensive Arabic corpora online.

The KITAB project relies on this corpus in its work on text reuse detection (through which the project aims to discover relationships among texts by aligning those parts of them that share common wording). In the project’s workflow, a first step is manual tagging of the structural elements of the texts (headings and subheadings or, for example, the names that order biographical dictionaries). For a complete description of the tags, click here. To annotate the texts, we use EditPad Pro, a powerful text editor that supports Arabic and can easily handle large texts. Annotators start by collating each machine-readable file with a printed version of the text (ideally using a PDF from the internet, but alternatively, the physical object in a library).

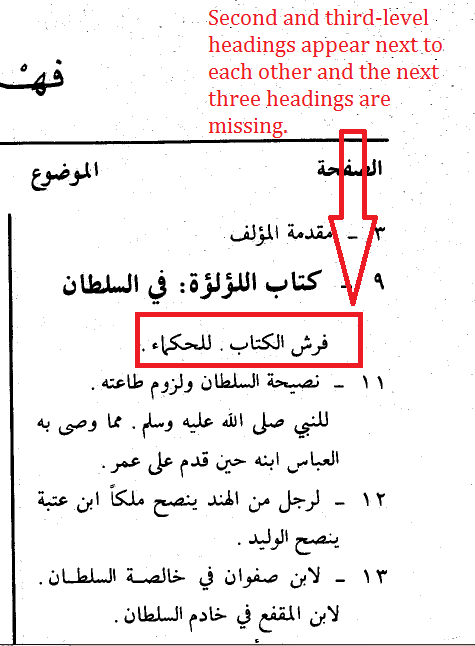

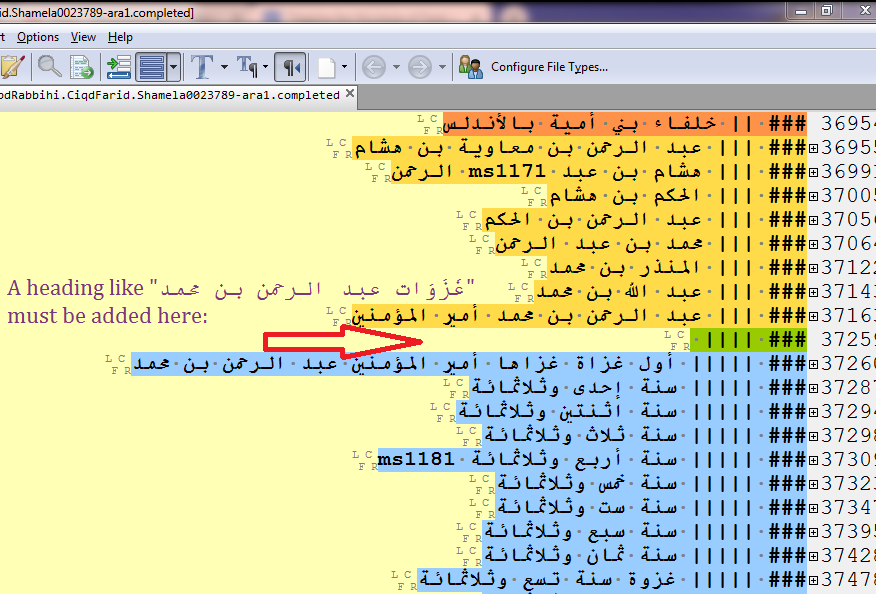

To briefly review the annotating of a text and some of the routine difficulties it involves, let’s have a glance at tagging the first few pages of a typical text in our corpus. Fortunately, the edition of the text in question – the ʿIqd al-farid by the author/compiler Ibn ʿAbd Rabbih (d. 328/940) – is both of high quality and accessible online (when it is not possible to find the same edition, annotators can use a different edition for collation; however, this needs to be done with care since two editions of the same text may well have a lot of differences). Although at this stage of preparing the text it is necessary to tag only the structural elements, this process presents its own difficulties and is not as simple as it might seem. For example, in most cases, annotators cannot rely on the books’ table of contents (TOC). This is partly because some structural elements (such as individual biographies) do not appear in the TOC. It is also because many published books do not have a TOC. Even when one is included, it may be practically useless for annotation. For example, a comparison of the book’s TOC and the human-annotated digital text in Figures 1 and 2, respectively, makes it clear that some of the headings in the text are missing in the book’s TOC. Moreover, the book’s TOC does not accurately reflect the way in which headings and subheadings are nested within the book itself. The heading titles are all presented as if they were parallel (except Kitab al-Luʾluʾa, which is set in bold), even though some of them are obviously subordinated to others. In addition, some empty header tags should ideally be added to make the structure coherent. As is evident from Figure 3, the author jumps to mentioning the holy wars (ghazawat) of one of the Umayyad caliphs in Andalusia without any heading specifying this shift.

Figure 1: The book’s table of contents.

Figure 2: The human-annotated text. The levels of headings are shown by the number of pipe symbols (|) in EditPad Pro, and the colours change accordingly.

Figure 3: Empty header tags should be added in appropriate locations to make the structure of the text coherent.

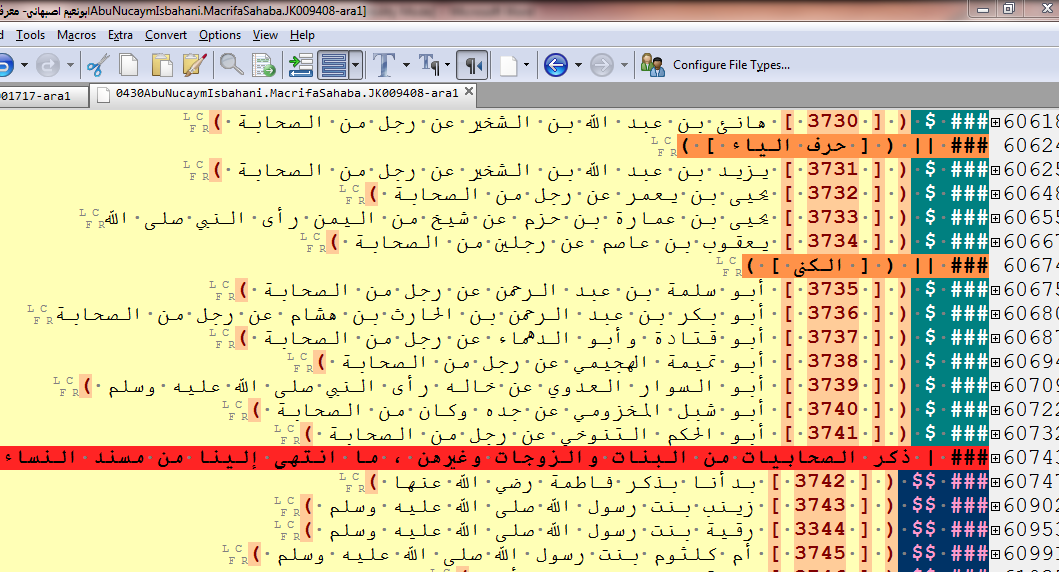

So, to present a useful annotation, annotators need to collate each page with a printed version in order to avoid missing headings, while at the same time exercising judgement about the relationship between headings and subheadings. When you consider that there are, on average, two headings per page in this text, for example, it is clear that the process of tagging can be extremely tedious as well as more intellectually challenging than the mechanical task it may initially appear to be. This is particularly true in cases where the annotator has to deal with editions in which the structure is poorly marked out or work on dictionaries or biographical collections which include thousands of entries or names, all of which need to be tagged (Figure 4).

Figure 4: A biographical collection including more than 4,000 name entries of men and women, tagged separately.

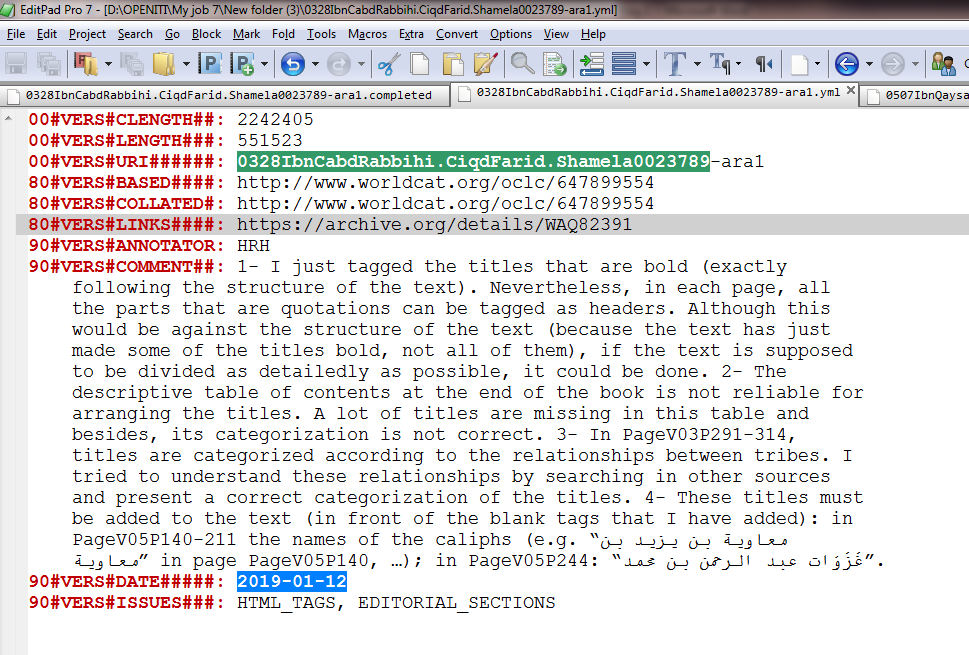

Each digital text is accompanied by a series of yml files. Figure 5 shows a yml file in which annotators keep track of their annotation by recording all relevant information. This includes providing a link to the PDF, links to both the edition of the digital text and the edition of the collated text in WorldCat, and any other explanation that is necessary for reviewers. All issues of the digital version (pagination problems, entering HTML tags into the text, redundant or missing parts, etc.) must also be reported in this file so that they can be fixed at a later stage. We also log the contents of the yml files as ‘issues’ on GitHub so that reviewers will double-check the texts at the next step. After vetting, these issues will be closed (click here to see the latest issues for annotated texts in our project).

Figure 5: A yml file.

To summarise, annotators must face probable shortcomings caused by the actors in the text production circle. This circle consists of two groups: (1) the producers of the digital texts and (2) the producers of the printed versions, including publishers, editors and medieval writers. On one side, there may be problems in the digital texts because they are produced by various research institutions and for a variety of different purposes. These institutions may change the structure of the texts intentionally by adding or deleting headings (to adapt the structure to their intended purposes) or make mistakes unintentionally. And on the other side, missing TOC, faulty TOCs and the inability to find and present the correct structure of the text are some of the problems related to publishers and editors. Even medieval writers can sometimes be a bother, as in many of their writings the thematic classification is so haphazard that annotators must spend a lot of time to understand the structure of the text they are working with. Each text usually involves unique difficulties that must be dealt with in a particular way, and our team is working hard to present all texts in the most accurate form possible. To date, 550 texts have been tagged, and more are in progress. Everything is openly accessible through our corpus, and we have a search engine to help you browse all the texts in the corpus (both annotated and not yet annotated). Click here to start browsing!