With text reuse detection, we rely on the power, speed and memory of a computer to find common passages between texts.

In our data so far, we can already see hundreds, or even thousands, of cases that point to the liquidity of the written tradition. By ‘liquid’, I mean that texts were often reused to form new books. For readers, it was nothing unusual to access old texts through new ones. This was true in the earliest times (e.g. third/ninth century) and continued in different ways for centuries afterwards.

One of the most important things our algorithm can do is show us more precisely where this reuse begins and ends between and among books. Looking into specific cases in our data, one thing is clear: when we consider transmission, we often think either too big or too small.

We think too big when we assume the book was the main game in transmission. Of course books were copied and transmitted onwards, but authors were also happy to incorporate large parts of earlier works into new ones. Our data encourages us to take more notice of other indications of partial transmission. The Ashrafiyya library catalogue, documented by Konrad Hirschler, contains a great number of multitext compilations and parts of books (including many identified with min, such as Min akhbar al-Baramika). There is also the popularity of anthologies, abridgements, literature in excerpts and other literary forms.1

By contrast, we think too small when we focus on the individual report or khabar or, at most, clusters of such reports. This is, indeed, where many scholars spend most of their intellectual energy, often with fruitful results.2

Text reuse detection helps us see what parts of texts were in fact transmitted in particular instances. The algorithm is basically indifferent to units of meaning; instead, it searches out patterns of reuse as strings. Methodologically, the role of text reuse detection should be similar to that of codicology in its focus not on meaning but on the isolation of features that tell us about transmission – here, chunks of words, rather than manuscript bindings. Like codicology and narrative analysis, text reuse detection belongs in the historian’s toolkit among other tools.

To give a typical example: the historian al-Tabari (d. 310/923) is commonly described as following Hadith methodology in his reporting on historical topics because of the detailed documentation that he provides for his sources. His reporting on the reign of the ʿAbbasid caliph al-Maʾmun (r. 198–218/813–33) features courtly intrigue against an important ʿAbbasid governor, ʿAbd Allah b. Tahir:

It is mentioned from ʿAtaʾ, the official charged with hearing complaints for ʿAbd Allah b. Tahir, who related that one of al-Maʾmun’s brothers spoke to al-Maʾmun thus, ‘O Commander of the faithful, ʿAbd Allah b. Tahir has an inclination toward the progeny of Abu Talib, just as his father had before him.’

ʿAtaʾ’s report goes on to quote al-Maʾmun’s brother proposing a way to catch ʿAbd Allah b. Tahir in the act of treason (and then reports on the governor’s honesty).3

What is noticeable from the text reuse data is that al-Tabari takes not just this report and this story but also the passages that follow it nearly verbatim from an unacknowledged predecessor, namely Ibn Abi Tahir Ṭayfur (d. 280/893).4 This means that we cannot rely on al-Tabari’s crediting ʿAtaʾ.5 Al-Tabari’s eye is not on this report specifically, but on something larger. To know this, we need to be able to read al-Tabari’s text alongside that of Ibn Abi Tahir. An isolated instance such as this one could be noted manually (often by pure luck), but what KITAB allows is work like this on a completely different scale and independently of isnads (chains of transmitters).

Similarly, a leitmotif in early Hadith transmission is a compiler’s travelling the world in search of reports. There is typically an assumption that such collectors sifted through reports one by one or, if they did so in larger units, that their primary focus was on the individual report (or on ‘collective isnads’).6 But was Hadith and Sira transmission so atomistic? We need to investigate this and can use text reuse data alongside current and innovative methods reliant on isnads and specific reports.

There are many cases to consider, such as an early collection attributed to Hammam b. Munabbih (d. 101 or 102/719–20). Scholars have noted for some time its close relationship to the Musnad of Ahmad b. Hanbal (d. 241/855) and also argued, persuasively, for its third/ninth-century origins. Now we can add text reuse data, with fifty-eight records of reuse in our first data set.7 The order of the passages mostly matches in the two works; this would seem to be reuse on a scale larger than the individual report.

We find many other cases with Ahmad’s Musnad. For example, Abu al-Qasim al-Tabarani (d. 360/961) reportedly travelled for some thirty years, learning and collecting Hadiths from a large number of masters in the course of a riḥla fi talab al-ʿilm.8 Our data reveals more than 3,700 records of common passages between his Muʿjam al-kabir and the Musnad, including many that occur in the same order, as our data visualisation shows.

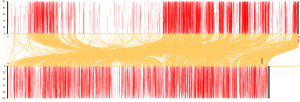

Graph 1: Ahmad b. Hanbal’s Musnad is laid out along the x-axis on the top in 100-word segments, and al-Tabarani’s al-Muʿjam al-kabir is laid out similarly in the bottom graph. The yellow lines show where our algorithm, passim, has detected shared passages of text. The consecutiveness of the reused passages suggests reuse of chunks of material.

The Musnad of Ahmad is the most ‘reused’ book in the current OpenITI corpus. To underscore a point I frequently make: we have a pattern here. The route of transmission requires closer investigation (direct or through common sources, for example). The process was no doubt complex, not a simple case of al-Tabarani copying out sections of the Musnad word for word. In fact, the many books that share arrangements with the Musnad are suggestive of complex networks of closely linked texts (as indeed the metanarrative underlying Hadith transmission would hold). But to see such patterns, the unit we need to investigate is not the solo report, but rather something much bigger.9

Reading for such patterns will require us to develop ways to assess the ‘edit distance’10 between texts and also ways to quantify the consecutiveness of reuse. The narrow goal should be to determine where common passages begin and end in specific cases. But the wider aim of such a textual forensics is to discern the norms governing different types of transmission and the ways in which authors negotiated them to make new meanings.

-

See Konrad Hirschler, Medieval Damascus: Plurality and Diversity in an Arabic Library (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), esp.68ff. and 134. For literary forms there is extensive scholarship; for excerpts specifically, see e.g. Muriel Debié, ‘L’historiographie tardo-antique: Une littérature en extraits’, in Sébastien Morlet, ed., Lire en extraits: Lecture et production des textes de l’Antiquité à la fin du Moyen Âge (Paris: Presses de l’université Paris-Sorbonne, 2015). ↩

-

On form and narrative structure, see e.g. Stefan Leder, ‘The Use of Composite Form in the Making of the Islamic Historical Tradition’, in Philip F. Kennedy, ed., On Fiction and Adab in Medieval Arabic Literature (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2005), 125–48; on sophisticated methodologies, see e.g. Harald Motzki, Nicolet Boekhoff-van der Voort and Sean Anthony, Analysing Muslim Traditions (Leiden: Brill, 2013). ↩

-

Al-Ṭabarī, The History of al-Ṭabarī, xxxii, trans. C. E. Bosworth (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 169ff. ↩

-

See Matthew Thomas Miller and Sarah Bowen Savant, ‘“Tell Me Something I Don’t Know!”: The Place and Politics of Digital Methods in the (Islamicate) Humanities’, International Journal of Middle East Studies 50/1 (2018), 135–9. ↩

-

In fact, Ibn Abi Tahir’s wording is ‘Al-Harrani told me: It is mentioned from ʿAtaʾ.’ In other words, al-Tabari has omitted as sources both Ibn Abi Tahir and this al-Harrani. Print edition: Ibn Abi Tahir, Taʾrikh Baghdad (Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 2009), 183ff.; see also two digitized versions here. ↩

-

For a summary of the phenomenon, see Chase Robinson, Islamic Historiography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 97; see also Fred Donner, Narratives of Islamic Origins (Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1998), 264–5, esp. n. 31. For another, parallel consideration of units of citation, see Antoine Borrut, Entre mémoire et pouvoir (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 21ff. ↩

-

Data set accessed on 24/4/2018 (books divided into 100-word chunks). Entry point: Musnad. Filtered for all matches with fifty records or more. Ordered, by date, with the Sahifa as the earliest work on the list (fifty-eight records). Musnad edition: Cairo: Muʾassasat Qurtuba, n.d.; Sahifa edition: Beirut and Amman: al-Maktab al-Islami, 1987, edited by ʿAli Hasan ʿAli ʿAbd al-Hamid. ↩

-

See Maribel Fierro, ‘Al-Ṭabarānī’, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. ↩

-

For an earlier study on Hadith reuse and the Digital Humanities, see Maxim Romanov, ‘Ḥadīṯ Reports in Ibn al-Ǧawzī’s (d. 597/1201) System of Argumentation (Based on His Talbīs Iblīs [“Devil’s Delusions”])’, in Khristianskii Vostok/Christian Orient, 2003/2009, 310–16 (in Russian). ↩

-

In computer science this term is used to refer to the way of quantifying how dissimilar two strings (of words) are to one another by counting the minimum number of operations required to transform one string into the other. ↩