For us as digital historians and corpus curators, faced with the complex history of reception and transmission as well as the distinct approach to learning and authorship, attributing authors to premodern Islamicate texts and representing this complexity within our corpus metadata is often a challenging task. Although it is especially daunting for composite texts, commentaries, and supercommentaries, the task is no less challenging when it comes to working with printed editions and online digital libraries, since we face the risk of reproducing editorial choices and biases, whether knowingly or unknowingly.

Most scholars are as cautious about digital editions as they are about uncritical printed editions. The manuscript, not the printed edition, is seen as the least mediated and most reliable link with the author, because even the most carefully edited texts are not free from editorial interventions. Most readers will be inclined to ignore the critical apparatus and go with the editor’s preference. Digital editions and e-books, however, tend to omit the critical apparatus. Moreover, many digital texts are typed by hand, and their origin and ‘witness’ printed editions are obscure. This adds to the challenges of curating a digital corpus with reliable metadata. In addition to text reuse data, accurate metadata is essential for mapping the Islamicate written heritage in a way that reflects its intertextuality and discursiveness. During the ongoing pandemic physical libraries were not accessible for several months, which created a perfect occasion to reflect on the reliability of digital texts available on the Internet. I will share the case of a modern gloss (taʿliqa) on a seventeenth-century Hadith commentary (sharh hadith) in the OpenITI corpus and follow its journey from manuscript libraries to print, to online digital libraries, and finally to our corpus.

Al-Taʿliqa ʿala al-Fawaʾid al-Radawiyya: A gloss on a commentary

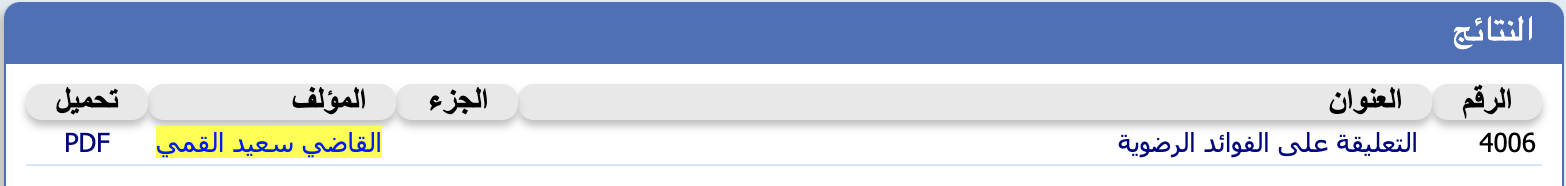

Author assignment issues are common in OpenITI corpus metadata and are often settled easily. However, my chance encounter with a text titled al-Taʿliqa ʿala al-Fawaʾid al-Radawiyya took me on a longer journey than expected. The Taʿliqa (‘Gloss’), which originated from the Shia Online Library (http://shiaonlinelibrary.com), was assigned in the metadata to the Safavid polymath Qadi Saʿid al-Qummi (d. after 1107/1695), known as ‘Hakim-i Kuchek’ (‘The Lesser Sage’), who was a student of the famous traditionist Mulla Muhsin Fayd-i Kashani (d. c. 1091/1680) and personal physician to Shah ʿAbbas II (r. 1052–77/1642–66).1 After going through the text, I realised that the metadata, as captured below in Figure 1, was misleading. The text was dominated by glosses by the leader of the Islamic Revolution of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (d. 1989), on Qadi Saʿid al-Qummi’s original text. Qadi Saʿid al-Qummi’s text was a commentary on a short dialogue between the eighth Twelver Shiʿi imam ʿAli b. Musa al-Rida (d. 203/818) and a Jewish Exilarch (Raʾs al-Jalut = Resh Galuta in Hebrew). The intriguing glosses by the young Ruhollah Khomeini, written in August 1929 during a summer retreat ‘from the glorious Qum due to the heat and the suspension of classes’ in his hometown of Khomein, included an introduction and a conclusion, as well as substantial comments on and even objections to Qadi Saʿid al-Qummi.2 It was clear that the Taʿliqa should be attributed to Khomeini, the last commentator, rather than to Saʿid al-Qummi. The metadata of the digital library thus omitted the history of the commentary tradition and only partially corresponded to the manuscript and to the printed edition. If we take a closer look at the reception of the Sharh and the manuscript tradition, it will become clear why metadata matters for corpus analysis.

Figure 1: Shia Online Library assigns the Taʿliqa to Saʿid al-Qummi despite the printed edition’s attribution of the text to Ruhollah Khomeini.

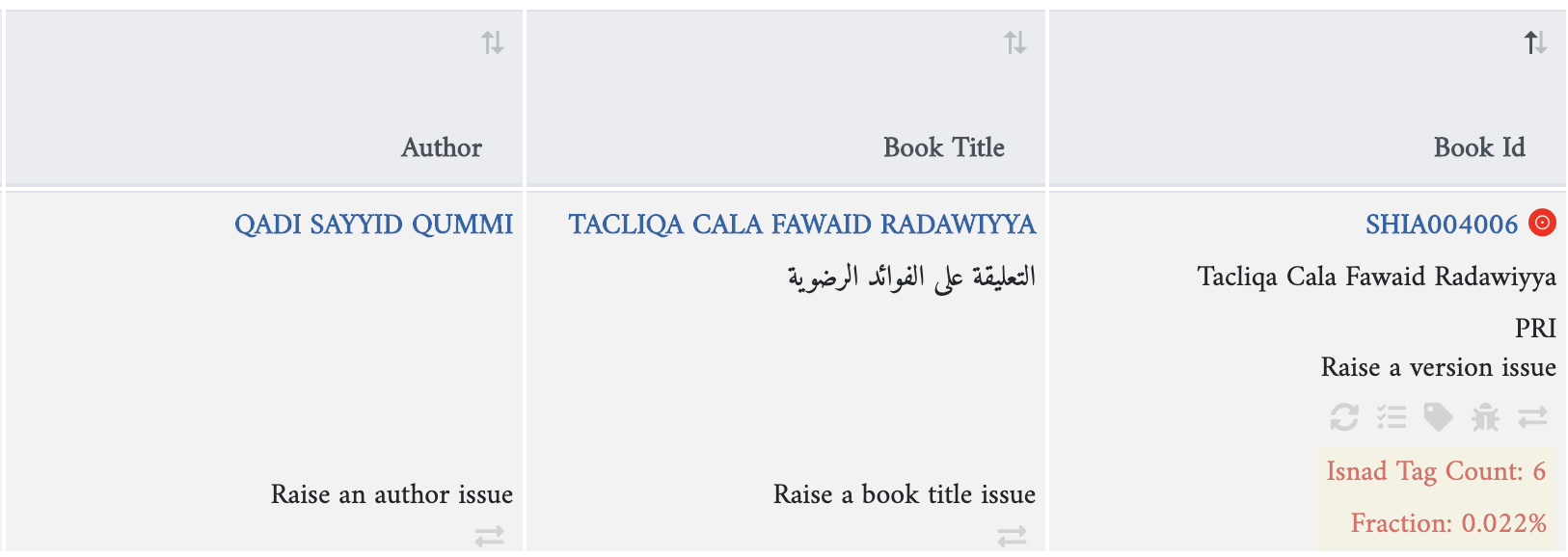

Figure 2: A screenshot of the OpenITI corpus metadata prior to correction. Now the application has Ruhollah Khomeini as the author, since we list the final author within the application (see the KITAB corpus Arabic metadata app at https://kitab-project.org/metadata). Users can also report similar mistakes via the system.

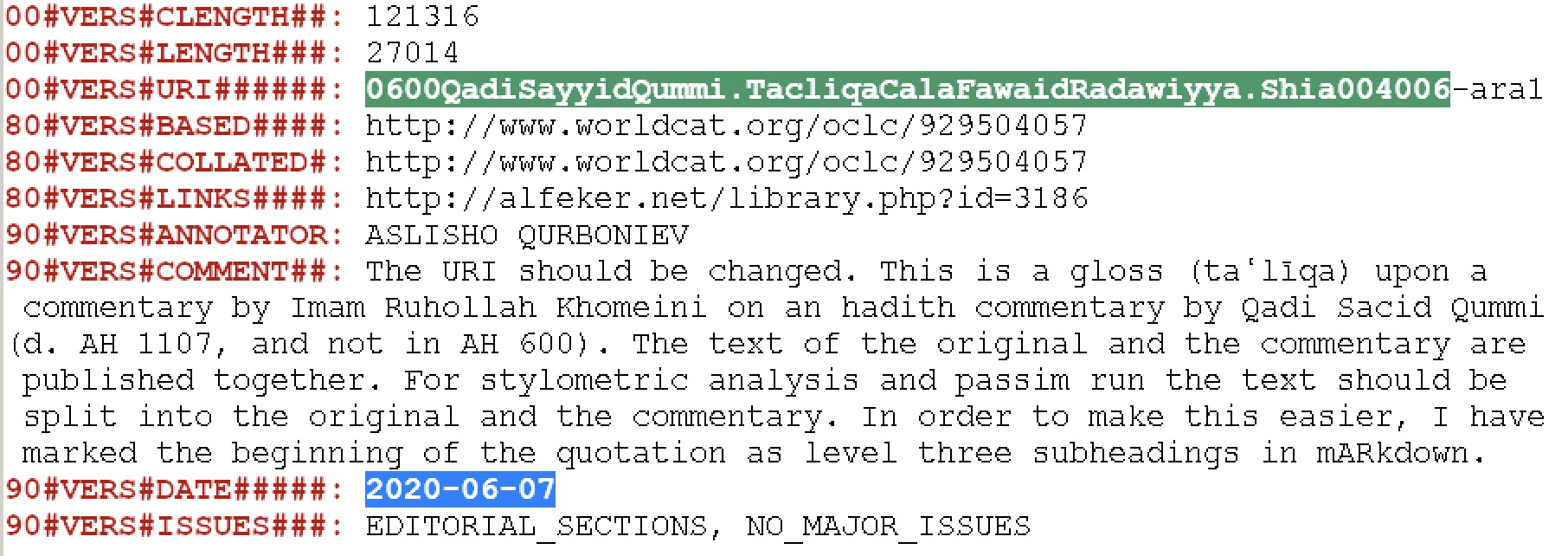

Figure 3: The completed yml file of the Taʿliqa in the OpenITI corpus. Curating the corpus includes annotating, creating reliable metadata, reporting issues and vetting by the KITAB team. The updated unique resource identifier (URI) is 1409RuhAllahKhumayni.TacliqaCalaFawaidRadawiyya.Shia04006-ara1.

The manuscript tradition

Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut, originally titled al-Fawaʾid al-Radawiyya, is a treatise by Saʿid al-Qummi from his incomplete Arbaʿinat (forty treatises on various subjects), which has been published separately.3 It constitutes al-Qummi’s commentary on ʿAli b. Musa al-Rida’s answers to questions asked by the Jewish Exilarch. While overwhelming and converting a Jewish scholar is a known topos in Muslim literature, the presence of a Jewish Exilarch in a medieval Muslim society is not a fiction. Geniza materials testify that the office of Exilarch continued at least until the fall of Baghdad to the Mongols in 656/1258.4 More elaborate versions of the interreligious debates of Imam Rida at the court of al-Maʾmun were first related by Ibn Babawayh (d. 329/991) in his Kitab al-Tawhid and ʿUyun akhbar al-Rida.5 These debates are well known and have been analysed by several scholars.6 It is, however, this short, enigmatic version preserved by al-Qummi that gave rise to a separate commentary tradition.

Only nine commentaries on Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut had been previously identified.7 Via the recently launched online manuscript catalogue of the National Library and Archives of Iran (NLAI) (https://hmi.nlai.ir/), I have located fifteen different commentaries, bringing the total number of records of different manuscripts of the commentaries to 132, most of them authored and copied during the nineteenth century (twelfth–thirteenth centuries AH) in Iran. This online catalogue, which is based on previously published catalogues, is very rich, but it still lacks some essential metadata information, such as the authors’ death dates and the language of each text. There are also identical records for no apparent reason, such as eight duplicates for various manuscripts of the Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut. Of course, given the challenges of this material and the current state of research, one assumes that not all manuscripts included in compilations have been correctly identified and catalogued. Nonetheless, the ‘National Memory of the Iranians’ project of the NLAI, which catalogues more than a million manuscripts from 1,868 libraries around the world, is unparalleled in its scope and ambition, and I think the present exercise proves this point.

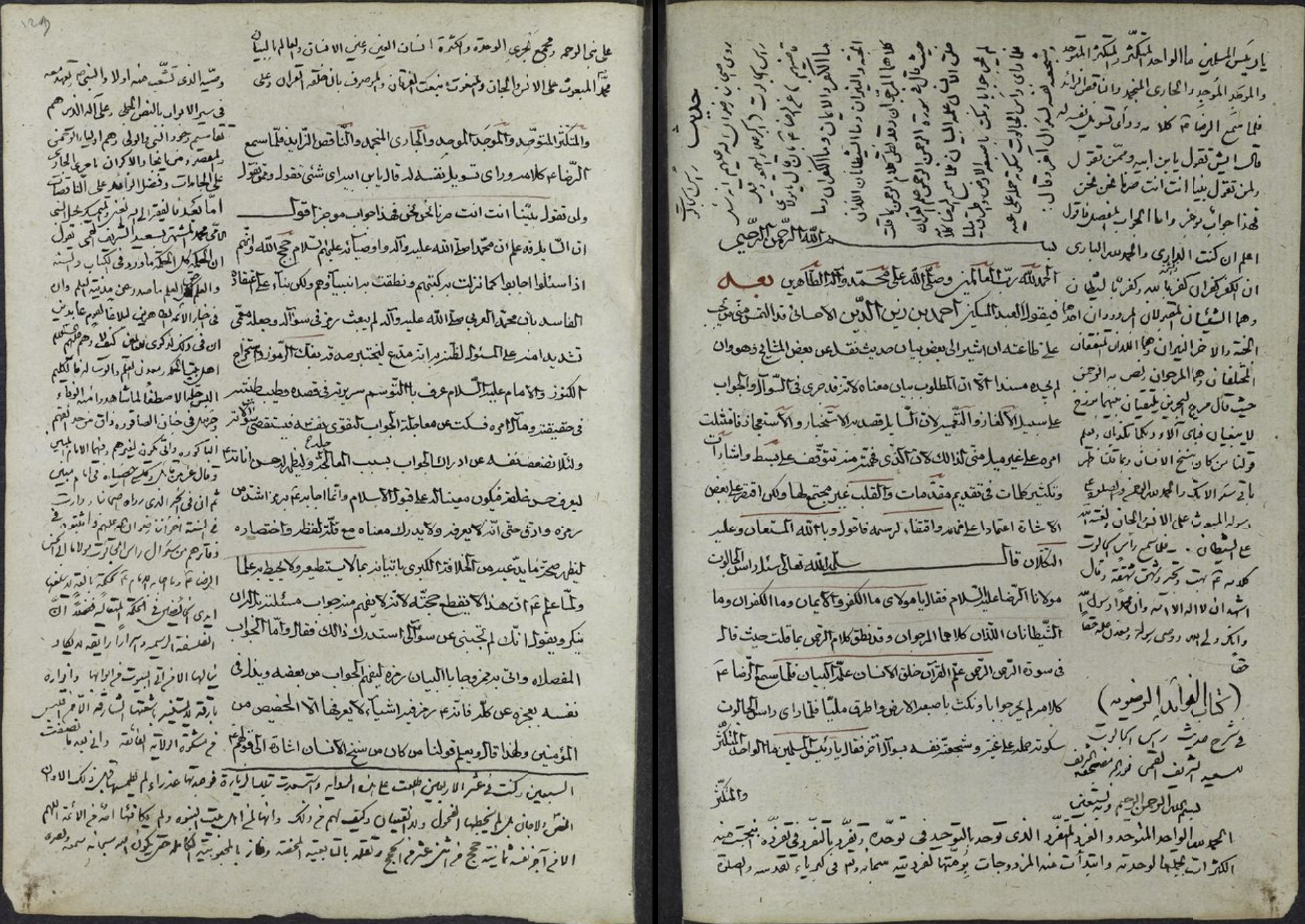

For an idea of the diversity and complexity of the Hadith commentary tradition, let us look at the following example (Figure 4). Here, Saʿid al-Qummi’s late seventeenth-century commentary was written on the margins of Ahmad b. Zayn al-Din al-Ahsaʾi’s nineteenth-century commentary in 1934 (1313 in the Persian solar calendar) by a certain Murtada b. Muhammad Sadiq al-Tabasi, known as Farhang. This use of the margins is hardly because of a shortage of paper in Tehran at the time. Farhang clearly thought the two texts should be read together. However, this kind of intertextuality, fluidity and discursiveness, which is characteristic of the manuscript culture, almost always becomes obsolete after the transition to printing.

Figure 4: The beginning of Shaykh Ahmad al-Ahsaʾi’s Sharh from a composite manuscript (Rasaʾil, mostly by al-Ahsaʾi, copied in 1821 in Rubat-i Pusht-i Badam village, Yazd province) with Saʿid al-Qummi’s commentary written on the margins of fols 126b–142a more than a century later in Tehran (1934). Courtesy of Princeton University Library.

| Commentators | Date of death | Titles | Number of manuscript copies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Qadi Saʿid al-Qummi, Muhammad-Saʿid b. Muhammad-Mufid | 1107/1695 | Al-Fawaʾid al-Radawiyya | 63 |

| 2 | Mulla ʿAbd al-Rahim b. Muhammad-Yunus al-Damawandi | 1158/1745 | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 7 |

| 3 | Mulla Mahdi b. Abi Dhar al-Naraqi | 1210/1795 | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 2 |

| 4 | Mirza Abu al-Qasim b. Hasan al-Jilani al-Qummi | 1231/1816 | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 18 |

| 5 | Muhammad-Baqir b. Muhammad, Mullabashi Shirazi | 1240/1824 | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 3 |

| 6 | Shaykh Ahmad b. Zayn al-Din al-Ahsaʾi | 1243/1826 | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 19 |

| 7 | Shaykh Muhammad b. Haj Muhammad-Hasan al-Mashhadi al-Tusi | 1257/1841 | Ghanimat al-Hijaz fi hall al-alghaz | 1 |

| 8 | Muhammad-Ismaʿil b. Muhammad-Jaʿfar al-Isfahani | 1280/1863 | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 2 |

| 9 | Mulla Muhammad b. Ahmad b. Mulla Mahdi al-Naraqi, known as ʿAbd al-Sahib | 1297/1880 | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 5 |

| 10 | Muhammad-Hasan b. Ahmad Nazari | fl. 13th/19th century | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 2 |

| 11 | Najafquli Anjudani | fl. 13th/19th century | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 1 |

| 12 | Sayyid-ʿAli b. Muhammad-ʿAli, Husayni Maybudi | 1313/1895 | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 2 |

| 13 | Muhammad-Husayn b. ʿAbd Allah al-Isfahani | 1362/1943? | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 3 |

| 14 | Anonymous | Sharh Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut | 3 | |

| 15 | Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini | 1409/1989 | al-Taʿliqa ʿala al-Fawaʾid al-Radawiyya | 1 |

| Total | 132 |

Table 1: A list of all known commentaries on Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut with the number of manuscripts that I could locate of each commentary in manuscript libraries (including multitext compilations). The earliest was written by Qadi Saʿid al-Qummi in 1099/1688, while the last one, Khomeini’s Taʿliqa, was written in 1348/1929.

To my knowledge, only three of the above-listed commentaries, including Khomeini’s Taʿliqa, have been published.8 These three are also available in digital format. Some manuscripts are probably still uncatalogued and unknown. For instance, just five commentaries were identified by Agha Buzurg Tihrani (d. 1970) in his comprehensive bibliography of Shiʿi works, al-Dhariʿa ila Tasanif al-Shiʿa.9 Only with the current rapid digitalisation are we beginning to get a better view of the Islamicate textual tradition. But we have yet to fully realise how our understanding of premodern book culture has been formed, and in many ways limited, by what is available in print. Let us consider some of these limitations, taking the Taʿliqa as an example.

The digital text of the Taʿliqa in the OpenITI corpus

The digital text of the Taʿliqa in our corpus has inherited several deficiencies from the printed edition on which it is based, and added several more:

-

The text of the original commentary by Saʿid al-Qummi and the gloss by Ruhollah Khomeini are not marked clearly.

-

The original colophon by the author and a note by the copyist, a certain al-Lawasani, are both present, but they are not marked clearly. In this case, the printed edition follows the manuscript copy.

-

In the manuscript, the glosses are reproduced on the margins of the original commentary, which is not how they are reproduced in printed editions. The glosses have been either moved to footnotes or printed on the same page following the main text, sometimes without proper visual signposts, as is the case with the present edition. This makes it difficult to see where the Sharh ends and the Taʿliqa begins. The digital text in the OpenITI, which is based on this edition, thus presents challenges for computational analysis. On the other hand, digital technology provides exciting possibilities for visual presentation of the text, including side-by-side reading, which will be available for the OpenITI in the future.

-

The metadata consists only of the title of the book and the name of the original commentator (Qadi Saʿid al-Qummi). No further essential information about him and the second commentator (Ruhollah Khomeini), the dates and places of writing and copying (i.e. Isfahan, 14 Rabiʿ al-Awwal 1099 AH and Khomein, 22 Rabiʿ al-Awwal, 1348 AH, respectively), the provenance of the manuscript, the work’s genre or topics, or other aspects of the work is provided.

In the ideal case scenario, all extant texts and commentaries of the ‘Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut’ should be included in the corpus, including the version preserved and commented upon by Saʿid al-Qummi and the more distant and complete versions of the debates by Shaykh Saduq in his Kitab al-Tawhid and ʿUyun akhbar al-Rida. Secondly, all the commentaries (more than a dozen, mostly in manuscript form) should be transcribed, converted into machine-readable format and added to the corpus, and the relationships between the texts should be recorded in the metadata. It is worth noting that the commentaries engage with other material besides strictly Shiʿi doctrines. As we can see from the citations and references in al-Qummi’s Commentary and Khomeini’s Gloss, the authors are in conversation not only with the Quran, the Prophet and the Shiʿi imams but also with Aristotle, Neoplatonists, the Ikhwan al-Safa, Ibn ʿArabi and post-classical Muslim philosophers and mystics, among others. This is where the strength of the text reuse method in mapping the intellectual tradition comes in. The real potential of the corpus approach and distant reading, of course, lies in the ability to go through a vast number of books and return all potentially related material.

In this case, after I raised the issue via an online system, the corpus manager, Lorenz Nigst, implemented the required changes to the authorship of the work in the work’s unique resource identifier (URI) and metadata. In more ambiguous cases, the issue would be discussed at one of the corpus meetings with team members. To facilitate further research, all relevant information about the transmission, authorship and provenance of the text and its explicit relationship to other texts in the corpus (e.g. that between al-Ghazali’s Tahafut al-falasifa and Ibn Rushd’s response, Tahafut al-Tahafut) is recorded in the metadata. That being said, the attribution of a URI and metadata constitutes neither a final verdict nor a scholarly position on the authorship of a given text. By checking the quality and consistency of the metadata, the project team hopes to ensure the reliability of the corpus as a starting point for researchers.

The case of Hadith Raʾs al-Jalut thus illustrates the challenges of corpus-building and referencing of Islamicate texts in a way that reflects the history of their reception and transmission. Specifically, it highlights the complexities of assigning authorship to composite materials such as commentaries and glosses. Engaging with the content of the commentaries, while beyond the scope of this blog post, would also reveal that Hadith commentaries are highly intertextual and engage with a variety of topics and disciplines, including philosophy and mysticism. Moreover, Hadith commentary is a living and discursive Islamic tradition that flourishes to date. Finally, this example reminds us of the fact that most Hadith commentaries are still in manuscript form, while modern commentaries, especially those on digital platforms and TV channels, are increasing by the day.

-

Sajjad H. Rizvi, ‘Qāżi Saʿid Qomi’, in Encyclopaedia Iranica, online ed. (2005), http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/qazi-said-qomi (accessed 20 September 2020). ↩

-

Ruhollah Khomeini, al-Taʿliqa ʿala al-Fawaʾid al-Radawiyya, 2nd ed. (Tehran, 1378/1999). ↩

-

Qadi Saʿid al-Qummi, al-Arbaʿinat li-kashf anwar qudsiyyat, ed. Najafquli Habibi (Tehran, 1381/2002). Al-Qummi’s magnum opus, Sharh Tawhid al-Saduq, a three-volume commentary on Ibn Babawayh’s Hadith collection, exists in a digital edition and is currently being added to the OpenITI corpus. ↩

-

Isaiah M. Gafni, ‘Exilarch’, in Encyclopaedia Iranica, online ed. (1999), https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/exilarch (accessed 24 September 2020). ↩

-

Ibn Babawayh al-Qummi, Kitab al-Tawhid, ed. Sayyid Hashim al-Husayni al-Tihrani (Beirut, n.d.), 417–41; ʿUyun akhbar al-Rida (Qum, 1378/1999), i, 139–82. ↩

-

Steven M. Wasserstrom, Between Muslim and Jew: The Problem of Symbiosis under Early Islam (Princeton, NJ, 1995), 113–19; David J. Wasserstein, ‘The “Majlis of al-Rida”: A Religious Debate in the Court of the Caliph al-Maʾmun as Represented in a Shiʿi Hagiographical Work about the Eighth Imam ʿAli ibn Musa Al-Rida’, in Hava Lazarus-Yafeh et al., eds, The Majlis: Interreligious Encounters in Medieval Islam (Wiesbaden, 1999), 108–19; Michael Cooperson, Classical Arabic Biography: The Heirs of the Prophet in the Age of al-Maʾmun (Cambridge, 2004), 70–106; Christian Sahner, ‘A Zoroastrian Dispute in the Caliph’s Court: The Gizistag Abalis in its Early Islamic Context’, Iranian Studies 52/1–2 (2019), 61–83, at 69–70. ↩

-

Sayyid Muhammad-Rida Husayni, ‘Sharh-i Hadith-i Raʾs al-Jalut’, Mirath-i hadith-i Shiʿa 2 (1378/1999), 233–54. This is an edition of Mulla ʿAbd al-Sahib al-Naraqi’s commentary with a short introduction by the editor. ↩

-

These are the commentaries of Saʿid al-Qummi, Khomeini and ʿAbd al-Sahib al-Naraqi (for which see Husayni, ‘Sharh-i Hadith-i Raʾs al-Jalut’). ↩

-

Agha Buzurg Tihrani, al-Dhariʿa ila tasanif al-Shiʿa (Beirut, 1983), xiii, 199/696; xvi, 70/349, 340/1581; xxvi, 285/1423. ↩