Measuring variation in the early tradition

In this first blog post I begin a discussion of what our methods might be able to show us about the early transmission of the written tradition. The case I take up involves the Muwattaʾ (‘the well-trodden path’) of Imam Malik b. Anas (d. 179/796), which is a foundational book for Islamic law and Prophetic traditions (Hadith).

What follows is quite detailed. Not all posts will ask as much of readers. But I think it is worthwhile to start with the early written tradition, where a lot of the debates and confusion lie. In particular, I am curious to probe how much variation there is between different transmissions of an author’s text.

Anyone interested in how the written Arabic tradition emerged, in the decades before and after Malik’s lifetime, needs to take seriously the ideas of Gregor Schoeler, who has illuminated the complex ways in which the written tradition developed. His most important insights relate to the inseparable mixture in early Islam of modes of oral and written transmission. This situation is reflected in the existence of hypomnemata (draft notes and notebooks), which passed into syngrammata (actual manuscript books). What began as aides-mémoire became in many cases, by the third/ninth century, fixed, ‘published’ books. Schoeler was not the first to offer such nuance, but his explanation was the most forceful and clearest, at least in Europe and North America (his work has been published in German, French and English). By contrast, much earlier scholarship set oral and written transmission in opposition to one another.

Schoeler, then, has made us think harder about the cultural meaning of ‘books’ in the early periods of Arabic and Islamic history. Were hypomnemata properly speaking ‘books’? The same applies to authorship – where transmission is complicated, do we need to be more careful in attributing ideas to an original author or a text, rather than to a student who may have changed it? Similarly, where students may have had different lecture notes covering the same topics, for example, what authority do we assign to the original teacher/‘author’? How do we distinguish his voice from that of his students/transmitters? And generally speaking, how are we meant to read, cite and understand the many works from the early periods that sit on shelves now – including the Muwattaʾ?

The complexity of the Muwattaʾ’s transmission has been known for centuries: the Maliki jurist Qadi ʿIyad (d. 1149), for example, referred to twenty different transmissions of the Muwattaʾ, although he said his contemporaries knew thirty. Modern editors and scholars also often mention large numbers, including Yasin Dutton (in his 1999 book The Origins of Islamic Law, where he lists nine or ten ‘versions’, either in complete form or as fragments). Malik reportedly updated his lectures throughout his life, which explains the changes. But despite summaries of differences (e.g. by Ignaz Goldziher), there has been very little by way of detail proposed on how precisely these texts differ.

We can now furnish far more evidence than was previously available for these differences – and also for differences in the transmission of other texts. This should provide a new evidentiary basis for addressing the bigger questions and help us engage with what have often been tentative proposals.

I have begun to compare three different texts bearing the title Muwattaʾ, originally pulled from Shamela and now in the OpenITI collection. They are credited to the following figures:

-

Yahya b. Yahya al-Laythi (d. 234/848–9). Yahya is by far the best known transmitter, and his transmission became the basis for the modern English translation of the Muwattaʾ by Aisha Abdurrahman Bewley. Yahya’s relationship with Malik has been debated in scholarship (there is one view that he studied directly with Malik), but as Maribel Fierro has argued, Yahya was ‘undoubtedly the pupil of Mālik’s pupils such as the Egyptians Ibn Wahb (d. 197/812) and Ibn al-Ḳāsim (d. 191/806)’.1 Yahya is considered to have introduced Malik’s Muwattaʾ to al-Andalus. His transmission of this work became canonical in the Islamic West and was also widely diffused in the East. It formed the basis of many commentaries. Our electronic edition is based on the printed edition prepared by Muhammad Fuʾad ʿAbd al-Baqi (Beirut: Dar Ihyaʾ al-Turath, 1985). The text in our corpus contains 146,475 words (OpenITI URI [uniform resource identifier]: 0179MalikIbnAnas.Muwatta.Shamela0001699-ara1).

-

Abu Musʿab Ahmad b. Abi Bakr al-Zuhri (d. 242/856). Abu Musʿab, from Medina, was reportedly the last person to have related the Muwattaʾ from Malik. Our edition is that of Bashshar ʿAwwad Maʿruf and Mahmud Muhammad Khalil (1412 AH/1991 CE). The OpenITI’s electronic version is digitised from on an edition based on a manuscript from Hyderabad, India. Various portions of this transmission also exist in manuscript form in Tunis, Qayrawan, Damascus and Dublin. Word count: 155,402 (OpenITI URI: 0179MalikIbnAnas.Muwatta.Shamela0008140-ara1).

-

Muhammad al-Shaybani (d. 189/805). Al-Shaybani was a younger contemporary of Malik and also a transmitter from Abu Hanifa (indeed, he is often reckoned a founder of Hanafism). One of the ostensible advantages of al-Shaybani’s text is that al-Shaybani was a contemporary of Malik, and since Goldziher, at least, his text has been described as a version of the Muwattaʾ.2 Our edition is that of ʿAbd al-Wahhab ʿAbd al-Latif (Beirut?: al-Maktaba al-ʿIlmiyya, n.d.). Word count: 63,443 (OpenITI URI: 0179MalikIbnAnas.Muwatta.Shamela0016050-ara1)

All three of these transmissions were among those used by Dutton in his The Origins of Islamic Law.

Two issues do become apparent when we compare the electronic versions3 of these different texts using our software, called passim.

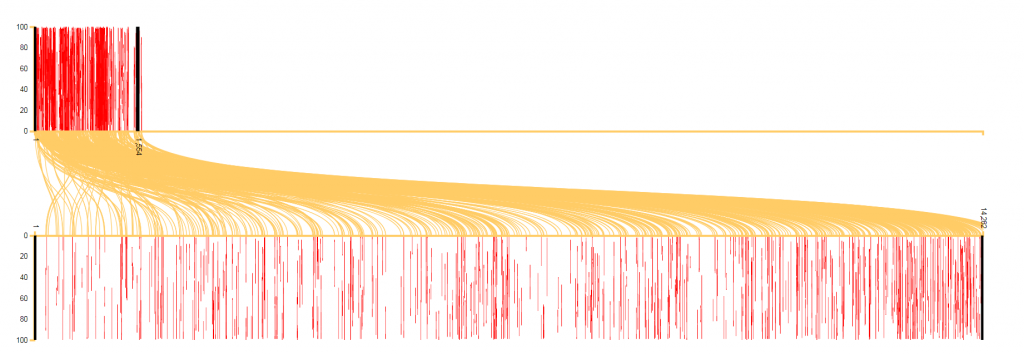

The first issue has been generally known, but neither in full extent nor in full detail. It is that the wording of Yahya b. Yahya’s transmission is close to that of Abu Musʿab’s, but their order is significantly different. Our data visualisation below compares the two transmissions.

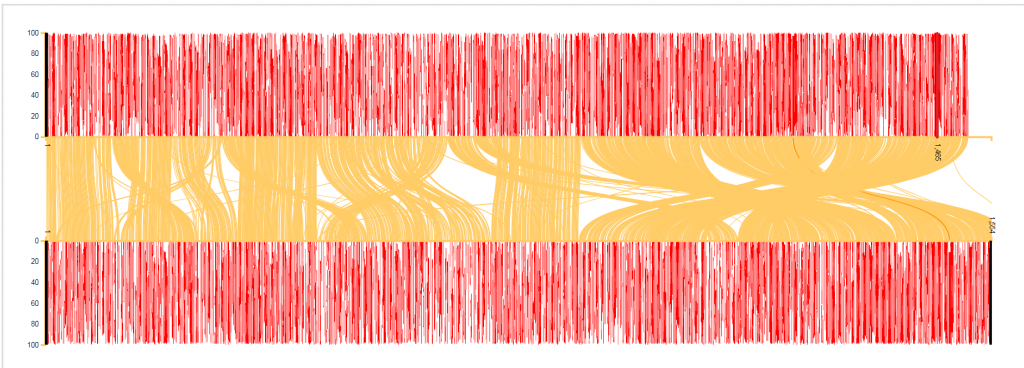

Graph 1: Yahya b. Yahya’s transmission is laid out along the x-axis on the top in 100-word segments, and Abu Musʿab’s is laid out similarly on the bottom. The red lines mark shared text passages (the longer the red line, the longer the passage). The yellow lines show where the shared passages fall in the two works.

The difference in order can be seen clearly by looking at the yellow lines. When they cross, we can detect rearrangement, and there are at least seven parts of the text that have been rearranged:

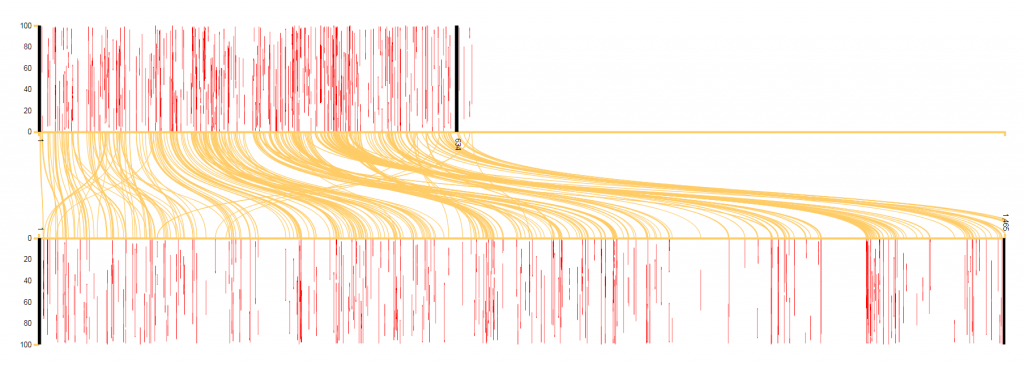

Graph 2: As in graph 1, but the crossing over of the yellow lines indicate divergences in the sequence of common passages.

Such data and graphs are just the start of the enquiry, but they show the close relationship between the two texts. In terms of overlap, we find that about 77% of Yahya’s text can be found in that of Abu Musʿab, and that about 72% of Abu Musʿab’s text can be found in that of Yahya (the percentages differ because the two books are of slightly different sizes – Abu Musʿab’s book is larger, so the common passages represent less of it). On their own, the data and visualisations say nothing about the stemmatic relationship between the texts. But they do open up areas for investigation using the aligned texts that accompany our visualisations, as we can see precisely where the differences lie, including at the bigger structural level. This means that so-called close reading can now be guided by ‘distant’ reading.

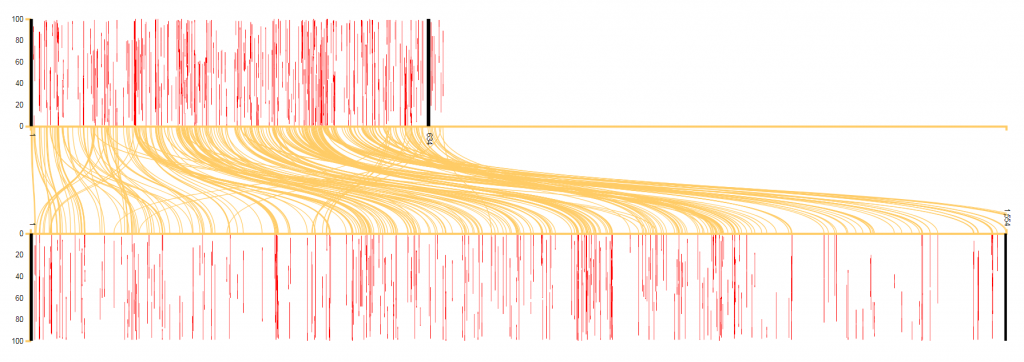

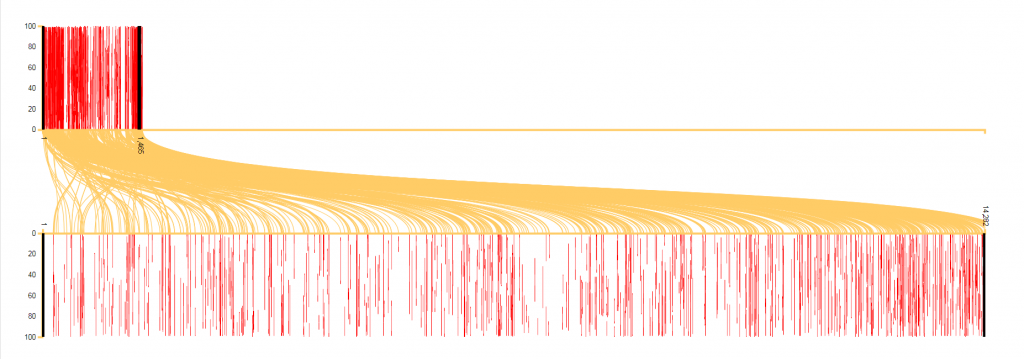

The second issue to become apparent is that it is very hard to consider al-Shaybani’s text a straightforward ‘version’ or ‘recension’ like those of Yahya and Abu Musʿab. If we compare al-Shaybani’s text with either of the latter two, the density of the relationship is much lower. Our data shows specifically that less than 25% of al-Shaybani’s text matches that of either of the other Muwattaʾs. Likewise, only about 10% of these (longer) texts matches the Muwattaʾ attributed to al-Shaybani.

When represented graphically, in fact, al-Shaybani’s text looks a lot more like a commentary on the Muwattaʾ than a straightforward version of it.

Graph 3: Al-Shaybani’s text is laid out along the x-axis above, and the Muwattaʾ transmitted by Yahya is below.

Graph 4: Al-Shaybani’s text is again laid out along the x-axis above, now with the Muwattaʾ transmitted by Abu Musʿab below.

I say that al-Shaybani’s text looks like a commentary because a commentator often reuses words from the commented text and accompanies them with his/her own words that explain it. So you would expect to see shared passages, but they would not be continuous. Graphically, a commentator’s words would result in white space on the graph. For example, in Graphs 5 and 6 below, we have comparisons of a self-proclaimed commentary on the Muwattaʾ – al-Tamhid li-ma fi al-Muwattaʾ min al-maʿani wa-l-asanid by the Cordovan Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr (d. 463/1070) – with the transmissions of the Muwattaʾ by Yahya and Abu Musʿab.

Graph 5: Yahya’s text of the Muwattaʾ is laid out along the x-axis above, with Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr’s commentary on the work below (OpenITI URI: 0463IbnCabdBarr.TamhidMuwatta.JK000585-ara1).

Graph 6: Abu Musʿab’s Muwattaʾ is shown in the top part of the graph, and Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr’s commentary is laid out below.

Closer reading is required to be more specific about how we should in fact classify al-Shaybani’s text, but the data does raise questions, especially about the relationship between al-Shaybani’s text and Malik’s teaching. One possibility is that the former is a commentary. But al-Shaybani had direct access to Malik. Was he commenting on the Muwattaʾ already in Malik’s lifetime? It would be significant for the tradition at large if this constituted an instance of a commentary preceding a work’s finalised version. But there are other possibilities. For example, perhaps al-Shaybani’s text reflected an early version of the Muwattaʾ, whereas those of Abu Musʿab (also likely a contemporary) and Yahya were the result of different participation in Malik’s lectures and the subsequent formation of a consensus? More digital files of other editions and manuscript transmissions would be helpful. And surely specialists in Islamic law and tradition can offer their own, expert readings of the data as it pertains to al-Shaybani’s text and the transmission of the Muwattaʾ.

It is noteworthy that the data we find on the Yahya and Abu Musʿab Muwattaʾs is consistent with the sort of complex environment described by Schoeler, where one would expect to find a lot of both precision (insofar as students transmitted faithfully) and change (insofar as Malik adjusted his readings across time). And it is also noteworthy that Schoeler seems to have intuited problems with referring to al-Shaybani’s text as a ‘recension’ of the Muwattaʾ. He uses the term with some obvious misgivings, and in fact his description of al-Shaybani’s text makes it sound a lot like a (critical) commentary on the Muwattaʾ. 4 Here, I think, intuition would benefit from a new evidentiary basis.

Often, discussions of texts such as the Muwattaʾ tend to revolve around questions of ‘authenticity’. Instead, when seeing textual variations such as this, I think we can ask ourselves far more interesting questions relating to the development of the written tradition. These pertain to the variety of ways of (re)using existing written texts, the malleability of the written tradition in different times and locations and for different types of texts, and the ways in which the producers of texts worked in practice. We have multiple ‘versions’ of many other early books in our corpus and also fragments of books reproduced in other books for which we have electronic files. These should also be studied alongside the Muwattaʾ to engage with these bigger issues.

In future blogs, then, I will consider other cases.

Schoeler makes us think harder about the cultural meaning of ‘books’ and ‘authors’, with one scenario in mind. But this was just a start. What others can we discern?

-

Maribel Fierro, ‘Yaḥyā b. Yaḥyā al-Laythī’, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. ↩

-

As Ahmad b. ʿAbd al-ʿAziz Al Mubarak says in his introduction to Bewley’s translation: ‘Another version of the Muwaṭṭaʾ worthy of mention is that of Imām Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan ash-Shaybānī which has great distinction. It includes the transmission of many traditions intended to support his madhhab and the madhhab of his Imām, Abū Ḥanīfa. Sometimes he mentions that Abū Ḥanīfa agrees with Mālik regarding the matter under discussion.’ Joseph Schacht lists the ‘recension’ and ‘edition’ of al-Shaybani in his elaboration of the Muwattaʾ’s history in his Encycopaedia of Islam articles. ↩

-

The predominant way of generating digital texts has hitherto been double-keying, which is extremely accurate. For a study on the matter (albeit for German), see Susanne Haaf, Frank Wiegand and Alexander Geyken, ‘Measuring the Correctness of Double-Keying: Error Classification and Quality Control in a Large Corpus of TEI-Annotated Historical Text’, Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative, no. 4 (March 8, 2013). ↩

-

Schoeler writes in The Genesis of Literature in Islam, trans. Shawkat Toorawa (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), 78, of ‘the two most important recensions’ but describes the second of them (after that of Yahya b. Yahya) as ‘the recension of, or rather the reworking (Fr. remaniement) by, the Ḥanafī Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Shaybānī (d. 189/804), who was a student of Mālik’s, one that distinguishes itself above all by its critical comments about Mālik and about the teaching of law in Medina. Al-Shaybānī’s comments appear at the end of most of the chapters and are not always in agreement with Mālik’s juridical opinion, or with the ḥadīths Mālik quotes. Notwithstanding the fact that he is a transmitter of Mālik, al-Shaybānī constantly has recourse to the juridical opinions of his Ḥanafī colleagues, which very often contradict those of Mālik, and to the opinion of his teacher, Abū Ḥanīfah (qawl Abī Ḥanīfah), with which he always agrees.’ ↩